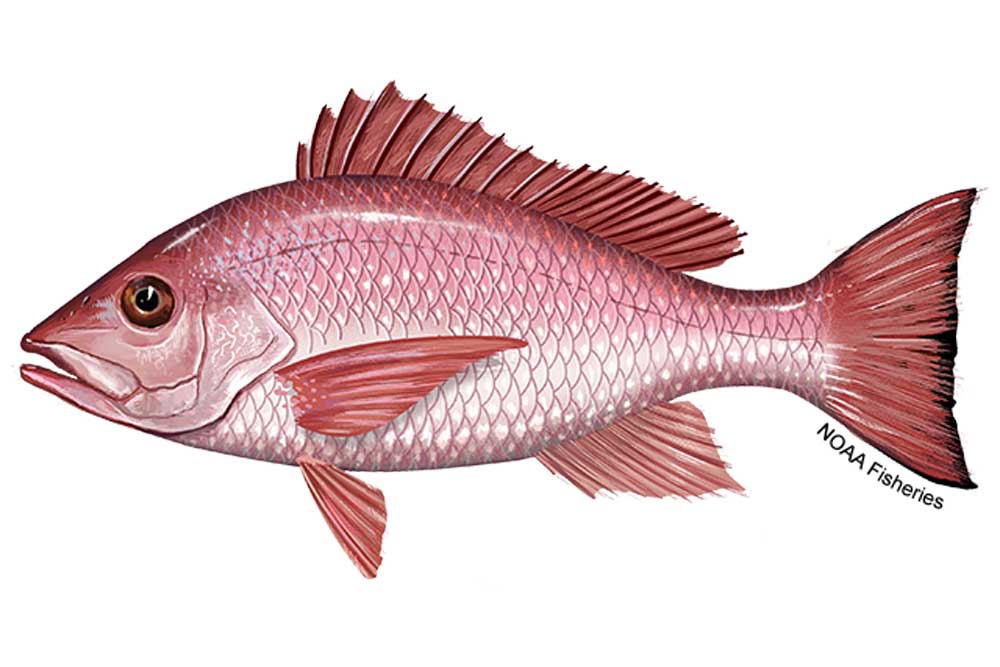

Last July, the National Marine Fisheries Service proposed a temporary closure of the commercial and recreational fisheries for red snapper in the South Atlantic for half a year, and possibly a year, to stop overfishing of the species. The 5,000 square mile zone stretches from waters just north of the Georgia border to just south of Cape Canaveral. Fishing, possessing or selling red snapper would be prohibited for recreational or commercial fishermen. Charter vessel or headboats, or boats for hire, would be banned from fishing for snapper in either state or federal waters.

After publishing the proposed rule and soliciting public comment, as government agencies are required to do before adopting regulations, the fisheries service received 1,151 comments. Of those, 1,102, or 96 percent, opposed the proposed rule in one way or another. Just 27 were in favor. (Twenty-two comments that had nothing to do with the rule were also filed.)

Federal regulation isn’t a popularity contest. The rule was adopted over the loud and angry objections of commercial fishermen and charter and headboat owners, including many in Volusia and a few in Flagler County. The rule was imposed by the South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council, one of eight such regional councils tasked with implementing the requirements of the Magnuson-Stevenson Act, the nation’s fisheries-protection law originally passed in 1976. It requires the fisheries service to manage the nation’s commercial waters against foreign intrusion or domestic overfishing.

On Wednesday, the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council voted 9-4 to extend the fishing ban indefinitely, while it prepares a management plan for the fishery. The red snapper joins the goliath grouper and the Nassau grouper on the list of fish no one may harvest in the South Atlantic. The new measure includes provisions that could impose fishing bans on all 73 species in the snapper-grouper family managed by the fisheries service.

Commercial fishermen and charter boat operators are incensed. (Charter vessels charge a fee for the boat rental as a whole; headboats charge a fee per angler on board.) They claim that their livelihood is being decimated by the rule, and they ridicule the fisheries service’s claim that the rule was necessary to protect the fish from being further decimated. Are they right?

There’s no question that the methodologies and statistics the federal fisheries service relies on for its conclusions are nowhere near uniform. Some of the research is based on landings collected in the 1940s. Some of it is from headboat catch records dating back to the 1970s. Some of it is based on surveys of recreational fisheries by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. All of it is also predicated on a wholesale switch in understanding about the red snapper, which was once believed to live a maximum of 25 years. Now it’s believed to live more than double that, to 54 years. So when surveys show much younger fish, the conclusion is that red snappers aren’t being allowed to age as they once did, and therefore that they’re being overfished.

The fisheries service reached that conclusion despite its own evidence showing vastly increased recreational landings of red snapper in 2007 and 2008, with 2007 estimates ranking at twice the numbers recorded in the 1995 estimates. Despite those increases, the age of the fish being caught is so low (less than 10 years old) that the conclusion remains the same: the red snapper is being overfished. There’s plenty there to raise questions, anger fishermen and put in question the viability both of the fisheries services’ research methods and the recreational and commercial boating interests.

But fishermen, recreational and commercial, are also exaggerating their own critical conditions. Some 220 commercial fishing vessels operated on average every year, between 2003 and 2007, in the snapper-grouper fishery extending from North Carolina to the Florida Keys. Those vessels generated total dockside revenue, among them all, of $9.78 million per year, or $44,500 per vessel. That’s for all fishing caught, not just red snapper. The red snapper banover a year was estimated to cost them, but not much—an average of $1,300 per vessel for a year in so-called net operating revenue.

The impact would be far greater for charter vessels—that is, recreational boats. But by nature, recreational fishing is a choice, not a necessity. And recreational fishing by far the larger part of the fishing equation in Florida. In other words, it’s far from essential. It does provide jobs. But at what cost?

From 2003 to 2007, an average of some 1,635 for-hire vessels operated in the snapper-grouper fishery from North Carolina to the keys, with each charter vessel generating an annual gross revenue in the range of $80,000 to $109,000 in Florida waters, according to the Federal Register. For headboats—the smaller proportion of boats that charge a fee per angler, but make more money doing so—the estimates are $220,000 to $468,000 for Florida vessels. About 16 headboats account for 70 percent of all the red snapper harvested by the headboat sector in the area stretching from Cape Canaveral to the Georgia border. Many of those headboats are in Volusia. There’s a far larger number of charter vessels operating in the area (a total of 1,553 are permitted to operate in the snapper-grouper fishery).

During the public comment period, all sorts of objections were voiced about the ban, almost 300 of which had to do with the economic impact of shutting down the fishery. The National Marine Fisheries Services Answer: There’s no question that boaters would feel an economic impact. But that impact is a matter of now or later. If the red snapper is being overfished, it will crash. If it does (as other species have), it will hurt boaters’ bottom lines (as many boaters have been bankrupted by other species’ crashes). Protecting the red snapper isn’t just about protecting the red snapper. It’s about protecting the future health of the fisheries that depend on the snapper.

Close to 200 comments disputed the fisheries service’s data. (All of that data and methodology is available here.) The fisheries service’s response to those comments was not as authoritative—and concedes that the data and models used in the stock assessments were not peer-reviewed by the National Academy of Sciences. Yet those are the assessments that decide the “science” that translates into regulation. For all its shortcomings, the methodology is, in a field where there is no exact science, far more broadly based than boaters’ allegation of haphazard data. Another assessment of the red snapper population is due later this year.

Holly Binns, manager of the Pew Environment Group’s Campaign to End Overfishing in the Southeast, which has been among the leading advocates of a fishing ban, said in a written statement issued immediately after the indefinite ban was approved: “The South Atlantic Council deserves credit for taking a significant step toward putting red snapper on the road to recovery. The red snapper fishing moratorium and closed ocean area are essential for a species that has plummeted to just 3 percent of healthy population levels and has been fished at unsustainable rates for more than 40 years. We understand this is a difficult time for some fishermen now, but this plan will help secure future fishing opportunities and a healthy ocean ecosystem that benefit tourism and all of our coastal communities.”

elaygee says

If they don’t stop overfishing, there won’t be ANY fish left to catch.