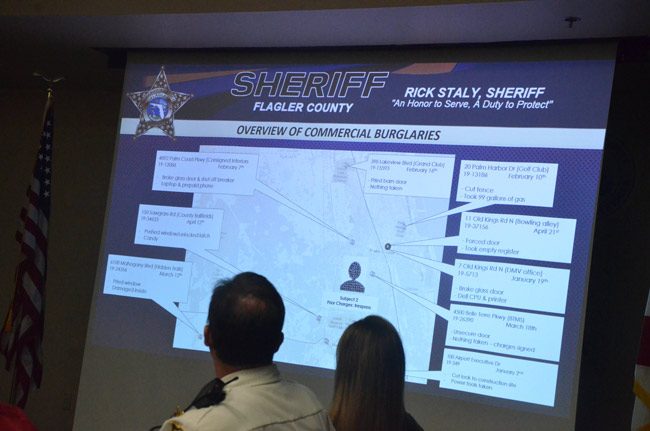

One map shows the nine commercial burglaries in Palm Coast and Flagler since January–the theft of 99 gallons of gas at the Palm Harbor golf course, the theft of an empty register from the bowling alley on Old Kings Road, the theft of a driver’s license printer from the Tax Collector’s office, and so on. There was no common thread, no indication of any linkage between them.

Another map shows the location of car breaks beachside–Bings Landing, Betty Steflick Park, the River to Sea preserve. Three individuals were identified as possible suspects, though in these cases “we’re not able to link them to the crimes,” says Sheriff’s Cmdr. Jeff Stuart.

A slide shows surveillance video taken from a ring.com residential door camera, acquired after reported break-ins in that neighborhood: it’s nighttime, a vehicle drives into a cul de sac rapidly, a man jumps out of the passenger side, runs to one door, then runs to another driveway, checking for unlocked doors. The thief knows Palm Coast’s notorious weakness: residents too frequently leave their homes and vehicles unlocked, so the majority of thefts occur as such crimes of opportunity.

In this case though, investigators used the video footage and other investigative techniques to locate the black Oldsmobile and the three juveniles–two of them from Volusia, one from Flagler–who were carrying out the burglaries. They admitted to them. That’s been the sort of issues plaguing the community more than anything, what the sheriff’s office calls its “Big 4 Focus”: burglaries, car breaks, stolen vehicles and robberies.

“We’re not looking at a front door being kicked in and a home invasion taking place,” Chief Chris Sepe says, though there’s been a 35 percent decrease in those crimes from 2018 to 2019, in good part because of what the sheriff’s office calls its Crimemaps strategy, where those maps and slides were shown earlier this week.

(© FlaglerLive).

Every week the command staff of the Flagler County Sheriff’s Office meets for what it calls “crimemaps,” an acronym that stands for “crime reduction, intelligence monitoring, employee management and agency performance summary.” It’s a local innovation that combines standard crime analysis tools–the mapping of crime clusters, trends, suspected criminals–with raw intelligence and targeted tactics, the whole forming a crime-fighting strategy the sheriff credits for sending the county’s crime rate to historic lows.

The second part of “crimemaps” is a bit less sexy: it’s the management and budget part of the operation, the financial numbers, the money in this or that fund, grants awarded, jobs open and filled, social media exposure and clicks (yes, they get all excited about those, too), but also the latest cumulative records on juvenile arrests and analyses of how well deputies’ crime reports convert into charges accepted by the state attorney–or rejections–which enables the agency to better train its deputies in the rigors of investigations and air-tight reports.

Put together, the two sides of Crimemaps meetings provide as forensic a perspective on the operations of the sheriff’s office from within its uniform and administrative ranks to the streets of Palm Coast and the county, and even Flagler Beach and Bunnell, whose police chiefs are an integral part of the weekly meetings.

More than two dozen people ring a set of tables arranged in a u-shape, from Sheriff Rick Staly down to his command staff–the meetings are usually led by Chief Paul Bovino–his supervisors and administrative staff, all of whom jump in at one point or another either to present their week’s report or to account for anything that may be amiss, anything that may be improved, or indeed anything that warrants congratulations: the meetings are a combination of both. “We debrief everything,” Bovino says, assuring a reporter that whether positive or negative, every issue is analyzed. Just as clearly, the meetings serve as affirmation and reinforcement of a strategy that, to its participants, appears to be working well.

It’s no small detail that Crimemap meetings are being held at the county’s Emergency Operations Center, generally the only place the sheriff can hold such meetings for now since the agency is without a permanent operations center of its own. This is part of what the sheriff refers to when he talks about the fracture of his operations–that, and the fact that he has certain programs and new strategies lined up, such as a real-time crime unit, that he can’t get started for lack of space.

The Crimemap meetings are closed to public and press, of course. But Wednesday Staly invited local reporters to sit in on a modified version of the complete, 90-minute Crimemaps.

“What you will experience today is what we do every week in this agency,” Staly said. “We look at the crime where it’s occurring, we focus our teams on those areas.”

The agreement was that everything said or shown in the PowerPoint could be used (nothing was off the record), with the understanding that meeting materials had been scrubbed of any sensitive, raw intelligence or certain investigative tactics: while some suspects’ and offenders’ names and images appeared on various slides, especially those of high-flying criminals, some were blanked out for being either still sought out or because the agency only suspects them to be involved in crimes, but doesn’t have proof yet. Much of the information was also a compendium of previously reported cases and incidents.

Two offenders’ names and images appeared prominently to illustrate how GPS ankle monitors have been successfully keeping domestic violence and other offenders from violating no-contact orders. When violations do occur, deputies are immediately notified, and re-arrests have followed. Probationers’ images and names appear on separate maps, indicating their status and when deputies last verified their compliance with probation terms: checks of the sort keep probationers on their toes, knowing that violations are taken very seriously (and can land them back in jail or prison). Several slides showed the identities and profiles of active warrants on fugitives and timelines of offenders’ upcoming releases from jail or prison, which would enable deputies to keep an eye on them as they reintegrate society.

Much of the remaining data was more analytical than offender-specific, including numbers on license plate readers, which have been used to find missing persons and make arrests. One such case involved an LPR “hit” that led to a Bunnell Police Department traffic stop on a vehicle with four occupants, all of them from out of county. The vehicle had been stolen in Gainesville. The occupants (a 16 year old, a 17 year old and two young adults) were also in possession of a black ski mask and a gun, suggesting that they had plans.

“The key here is not only do we focus on people but we get these focused locations, nuisance locations,” Bovino said, referring for example to the case of the house at 21 Fort Caroline, a house that had drawn innumerable complaints. “We throw all of our partners out there and we kind of make it miserable for them to commit crimes,” Bovino said. Eventually, all the occupants were arrested, or re-arrested: the four occupants had had no fewer than 54 arrests between them, over time, individuals Sepe wryly described as “not necessarily the most law abiding citizens at this point.”

On the other hand, the homeless, or crime associated with homelessness, was never once the subject of a slide, of a focus or of anyone’s discussion points. The sheriff has repeatedly told local government officials that he was not interested in becoming the homeless police (and homelessness in and of itself is not a crime). But the absence of any homeless-crime-related trends also illustrates the gap between the reality on the ground–where crime by the homeless is rare enough not to be a focused concern at crime-strategy meetings–and the exaggerated public perception of a “crisis” (as a resident described it to the Palm Coast City Council last month), fueled to some extent by political posturing. In Crimemaps, anyway, there is no such thing as a homeless “crisis.”

With reporters in the room there was a risk that the Crimemaps meeting would turn into a grandstanding opportunity for a sheriff keener than most on public and media attention. In fact, it was revealing in a much different way, showing him–once the television cameras had left the room–as he seems to be behind the scenes, almost entirely in work mode, mostly deferring to and trusting his command staff, none of whom seemed hesitant to speak their mind. The sheriff only occasionally jumped in to question one thing or another, offer reinforcement, or clarify an issue for the reporters. His staff was not inhibited and not obsequious toward its chief: it was not a groupthink session of yes-men but a gathering of men and women comfortable in their authority and in command of their responsibilities, which may explain at least as much as strategies like Crimemaps why the agency is less dysfunctional and more cohesive than it had been in previous years.

One of the more revealing slides is the graph showing the 911 center’s stats: a little over 10,000 911 calls (a slight increase from last year), but nearly 40,000 “officer-initiated” actions that are all channeled and documented by the communications center–actions never reflected in the volume of 911 calls, and that show the amount of police work conducted independent of residents’ requests or calls for help. That’s part of what Crimemaps instigates, Staly said, providing a more targeted and evidence-based framework for the deputies’ patrols.

So if we identify a hot spot in a neighborhood, that’s what the team goes out looking for, they’ll do extra patrols in those hot spots,” Sepe said. “If there’s traffic crashes taking place in one intersection, they’ll do more enforcement there. So all that stuff is officer-initiated.”

Technology is playing a greater role in how and where deputies and detectives do their work, but the sheriff and his staff was adamant that the technology is not displacing human intelligence. “What it does do is make our deputies more effective and efficient,” Staly said.

Leave a Reply