By Andrés Porras Chaves

In October 2016, the Swedish Academy announced that it was awarding the Nobel prize for Literature to the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”. The decision sent out shockwaves: for the first time, a musician had received the most prestigious literary award on the planet. It sparked debate, with many questioning the decision and even sarcastic suggestions that novelists could aspire to winning a Grammy.

The controversy fed into much needed debates on the boundary between poetry and song, but the question of what constitutes literature is much broader. Does it mean the same as it did in 1901, when the first Nobel prize for literature was awarded?

High and low culture

These questions date back far beyond 2016. In the late 1950s, a group of professors from the University of Birmingham founded a new interdisciplinary area of study, called cultural studies, in order to ask new questions: What was the role of TV and other mass media in cultural development? Is there a justification for distinguishing high and low culture? What is the relationship between culture and power?

These questions are all still relevant to current debates around literature. Often, the word “literary” is a status symbol, a seal of approval to distinguish “high” culture from more vulgar or less valuable “low” forms of culture. Comics, for example, were not invited to join the club until recently, thanks in part to a rebranding under the more respectable guise of “graphic novels”.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, literature displays “excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest”. It seems that an artist like Bob Dylan can take home the Nobel prize thanks to literature’s defining feature of “excellence of form or expression”, which is not strictly limited to the written word.

But how do we account for other language-based forms of expression? If performed works such as theatre or songwriting can be considered literature, where is the limit?

Word play: text-based video games

According to data from video game data consultancy Newzoo, more than 3 billion people play video games worldwide – almost half of the world’s population. In Spain alone, 77% of young people play videogames, making them a massively relevant form of culture. But what does this have to do with “excellence of form or expression”? To answer this question we have to look back several decades.

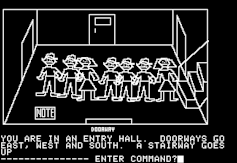

When the first video games were developed in the 1950s, two distinct genres emerged: one was action oriented (such as the pioneering 1958 game Tennis for Two), and the other more text based. The original written games, known as “interactive fiction”, were made up exclusively of text, and the player’s job was to read and make decisions that would determine the game’s outcome using a keyboard.

Wikimedia Commons

The inclusion of images in adventure games would not arrive until 1980, when Mystery House became the first “graphic adventure” game. These would reach their heyday in the 1990s: famous examples include the first two Monkey Island games (1990, 1991), Day of the Tentacle (1993), Full Throttle (1995), and Grim Fandango (1998), though there were many others. Despite technological advances, these games inherited several features from interactive fiction, including the predominant role of text.

The experience of playing one of these titles is not so different from that of a book: reading, pauses, the possibility of backtracking, and so on. The player spends most of their time in dialogue with various characters in search of information, stories, or even banter and jokes that are irrelevant to the game’s progress, much like footnotes or subplots.

Several classic adventure games even have direct links to literature: The Abbey of Crime (1987) is a Spanish adaptation of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, while the legendary insult sword fighting of The Secret of Monkey Island was written by science fiction author Orson Scott Card. In Myst (1993), the gameplay itself revolves around two books.

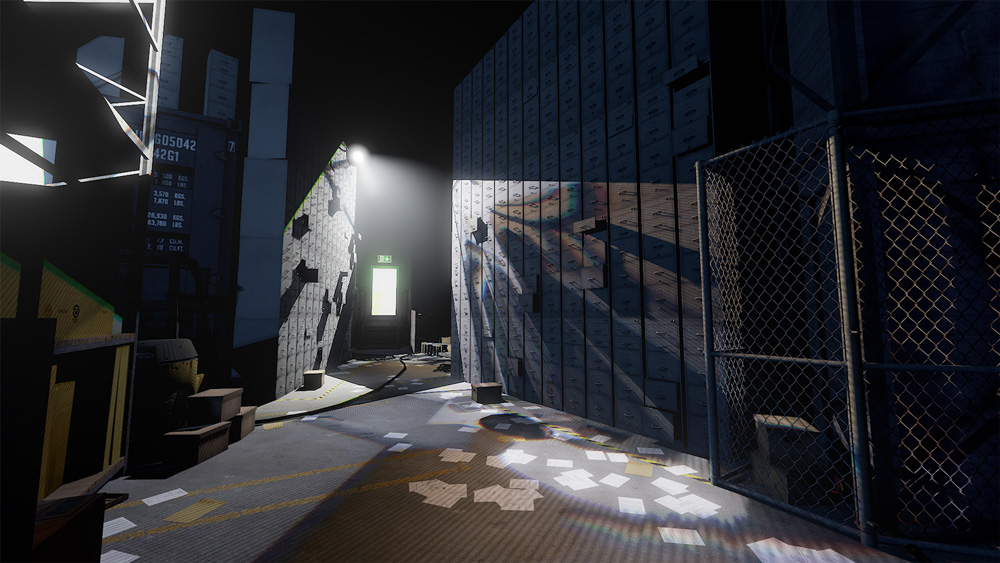

Literature on the screen: “story-rich” games

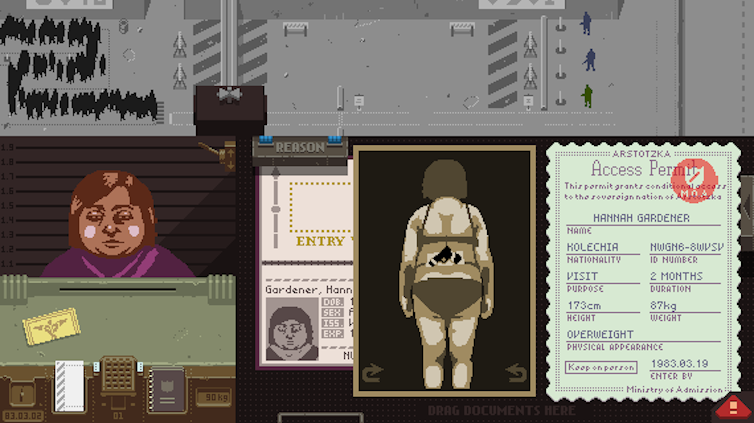

In more recent years, a new sub-genre of adventure games – known as “story-rich” games – has become popular thanks to independent creators and producers. In Papers, Please (2013), a border policeman in a fictional dictatorial regime deals with terrible moral dilemmas on a daily basis. In Firewatch (2016), players take the role of a forest ranger who investigates a conspiracy by walkie-talkie. In Return of the Obra Dinn (2018), the player must reconstruct a tragedy on the high seas with the help of an incomplete book and a peculiar compass. In all these cases, gameplay and visuals take a back seat to strong narratives.

Papers, Please

A quintessential example is The Stanley Parable (2011), where the player takes the role of a worker in a strangely deserted office. They have to explore several corridors while trying unsuccessfully to interact with their surroundings, accompanied by the voice of an enigmatic narrator. Upon reaching a room with two open doors, the voiceover states that Stanley “entered the door on his left”.

The player can choose to follow the instructions or disobey, provoking the wrath of the narrator much like in the denouement of Miguel de Unamuno’s 1914 novel Fog, where the main character speaks directly to the author.

Each decision then opens up new paths leading to dozens of possible endings, similar to a “choose your own adventure” book. Its fragmentary and disordered story – as well as its playful spirit – is reminiscent of Julio Cortázar’s 1963 novel Hopscotch. The experience of playing the game is marked by postmodern literary features – as described by critics like Mikhail Bakhtin or Linda Hutcheon – including metafiction, intertextuality and parody.

One of its creators – Davey Wreden, a critical studies graduate – also created The Beginner’s Guide (2015), a game in which the player moves through levels of failed video games to learn more about their mysterious creator. In one, the player’s task consists solely of wandering through a virtual cave reading the countless comments left there by other frustrated players.

Steam/The Beginner’s Guide

In recent years, the genre of digital or electronic literature has emerged, including books with QR codes, works that can only be read with virtual reality headsets, poetry collections published as apps, and so on. These works are fundamentally based on language, begging the question of why video games cannot also fit into this category.

This debate takes on added relevance today, as digital formats are having an undeniable impact on our reading habits. Just as today we accept oral cultures or popular music as literature, perhaps one day we will do the same with interactive stories like The Stanley Parable. Writing has always tried to break away from established ideas, and we know that literature is not limited to words on paper. Sometimes it pays to disobey the voice in our heads and walk through the door on the right, the one that leads to new, unexplored possibilities.

![]()

Andrés Porras Chaves is Profesor of humanities at IE University, Spain.

Pogo says

@P.T.

Thank you for putting this forward. I would rank it among the best from the Conversation site to appear on this site.