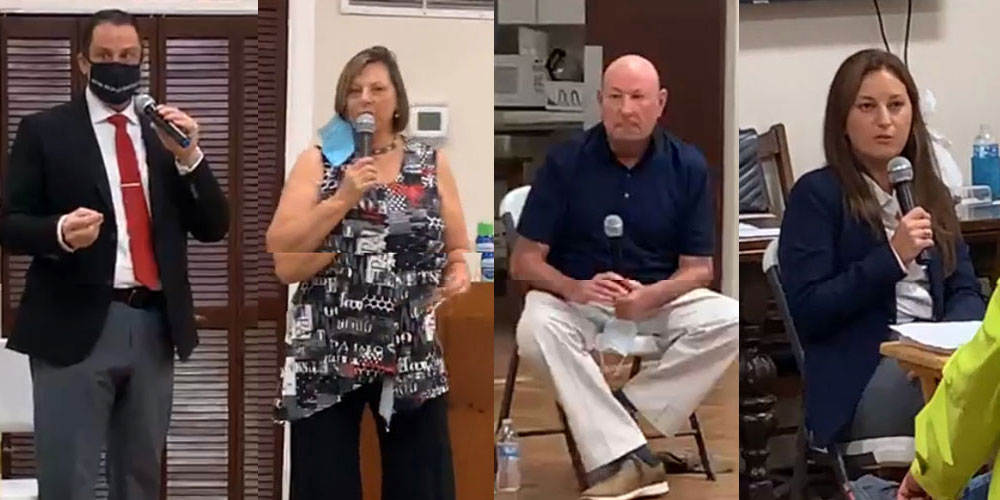

As it has done at every election, the Flagler Beach Woman’s Club Tuesday evening hosted the city’s only question-and-answer forum with candidates in the March 2 municipal election.

The pandemic had limited the number of people in an audience that usually draws standing-room crowds, there were no traditional cookies, but the hour-long event was shown live on Facebook and, as always, was kept briskly on pace by Margaret Sheehan-Jones, the club member who emcees the forums.

Two races are on the ballot. Incumbent Mayor Linda Provencher’s decision to step down drew three candidates: Kim Carney, the former city commissioner, Suzy Johnston, a Realtor and an almost permanent presence at city commission meetings since declaring her candidacy–she is running under Provencher’s mantle–and Pat Quinn, a political greenhorn. It was his chance to define his candidacy, but he had the least to say of the candidates, and said it in a voice that, like his ideas, has yet to find its footing.

First-term Commissioner Eric Cooley is running for reelection. He’s being challenged by Paul Harrington, who ran for a seat last year and the year before and lost–and who was a no-show Tuesday. Harrington, who tends to align with Carney, is in the midst of a code enforcement conflict with the city. He did not respond to an email asking him about the no-show, nor to a call to his cell phone, before this article published.

As always, the candidates introduced themselves before the questions.

Cooley said he’s been a resident for seven years, owning the Seven-Eleven across from the pier during that span, and serving on the city commission for the past three. Previously he’d been in corporate management for a couple of decades, a “cut throat” culture he wanted to leave behind, as he did Chicago. He cashed out his retirement, bought his store and is now “working in my retirement,” he said. He spoke of his frequent involvement in voluntary efforts from the now-defunct Feed Flagler to beach cleanup with the Flagler Beach All Stars and dune-vegetation efforts.

“Part of the things that you see when you’re involved in so many different activities is you find things that you think need improvement, you find things that you can probably add to. That’s how I got inspired to be a commissioner three years ago,” he said. Three years ago the general business climate was not business-friendly, he said. Changing parking designs downtown helped make matters more welcoming, he said, and efficiency at city hall improved (he credited the late Larry Newsom, who’d been hired two years before he was elected).

Suzie Johnston is in her first political campaign but came across as more seasoned than her years or political experience would suggest: she’s learned by osmosis, scion of a still-living and working political monument in the county (Tax Collector Suzanne Johnston). The younger Johnston–she is Cooley’s companion, a subject that did not come up in Tuesday’s questions–was born and raised in Flagler Beach and is raising her young daughter. She spoke of herself as a close ally of current Mayor Linda Provencher. “I knew when Linda P. was not going to run for mayor, it was time for me to step up to the plate. I’ve spent the last 30 years volunteering here in Flagler Beach and the last nine years working directly alongside Linda.” She is a member on the city’s FB3 business group and is a board member on the Flagler Education Foundation. “I have the energy and drive, I have the tools of my degree in business and marketing, but most importantly, I always give 100 percent,” she said. She spoke of “new solutions, new initiatives and a new set of eyes,” though she did not provide any in her opening statement.

Kim Carney was a Flagler Beach commissioner for nine years before she decided to challenge County Commissioner Dave Sullivan for his seat last November. She lost. She described her path as similar to that of Provencher, who’d also served on the city commission before becoming mayor. “Although I was not successful, I continue to believe that our city needs representation at the county level,” she said, hinting of a future run for a county seat. “I am not committing to a future run, but I did tell Mayor Provencher that I would run for mayor if I was not seated at the county.” She continued: “I can tell you that I’m not perfect. But I can also tell you that I am passionate,” describing herself as a citizen and taxpayer first. She said she hadn’t heard either of her opponents speak to specific issues, and said the race wasn’t about “popularity,” but about moving the city forward. “My style is about facts, not propaganda,” she said, though she did not give examples of “sunshine law violations” she said have damaged the city. (She gave an example of “propaganda” toward the end of the evening.)

Pat Quinn, a candidate for mayor, is the newcomer to Flagler Beach politics, though he’s had connections to Flagler Beach, through property and family, since 1995, and has been a full-time resident since 2007. He has 32 years in construction, was a carpenter in New York City, retiring in 2006 to move to Flagler Beach, where he opened a home-inspection company. He said he wants to see First Friday and the city’s parades return–rare is the voice that would not–and spoke of beautification, though he also revealed his distance from city matters when he had to ask the audience for the name of the city’s fire chief (Bobby Pace).

Topping the questions was the proposed hotel in place of the old farmer’s market–and the old hotel, demolished in the early 1970s. Quinn said he wanted to look at the blueprints, putting his construction experience to use, and was cautious against “eyesores.” Carney said she’s been a proponent of such a project, though “we should not jump just because we see an artist’s rendition,” which only projects what could go there. But that would have to be balanced with all city regulatory requirements. She cast a little doubt on underground parking (“it’s scary, but if it works and it passes the litmus test”) and spoke of preserving residents’ land rights. Johnston, too, is a proponent, recalling her grandmother’s stories of going to her prom on the top floor of the old hotel. The hotel would bring in tax dollars and visitors, she said, compared to “slim to none” accommodations currently. The hotel would also “extend our season,” she said.

Cooley echoed those thoughts. “The hotel was there before we even had codes. That is our history,” he said, speaking of the hotel in the context of the city’s community redevelopment agency, the enterprise zone for downtown. But he cautioned against making substantial changes to other landmarks such as Veterans Park, immediately to the east of the hotel property.

The questions at such forums can sometimes reveal the thinness of the questioner’s knowledge about the issue in play. For example, the candidates were asked whether they support “dredging” the ocean floor to add sand to the beaches, and if so, how would they get that accomplished. The first part of the question may have referred to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ plan, over 15 years in the works, to dredge a borrow pit seven miles offshore and dump hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of sand onto 2.6 miles of beach in the city, just south of the pier, rebuilding dunes and protecting both beach and roadway in the process. That project, set to recur with more dredging every decade or so, was to have taken place already but for a few property owners who have yet to sign easements to allow the project to go forward. (They will be taken to court if they continue to refuse, the county warns.)

But the project is already paid for in part with federal dollars, and in part by state dollars secured by county government. Flagler Beach is almost entirely a bystander. It’s not up to city commissioners to make it happen or to stop it, but up to the county and the Army Corps of Engineers to shepherd the project through its paces, as they are doing now. Still, the project’s controversies have been in the public eye for over a year, and the question gave the candidates a rare chance to contrast their different views sharply.

Carney has a long history of opposing the project. She called the Army Corps’ assurances “a lot of propaganda,” because the current ecosystem, in her view, will be hurt by the creation of a different ecosystem).

Johnston took a diametrically opposed view, and spoke as people familiar with Provencher’s style have come to expect from the current mayor: directly and sharply: “I have a different idea. I’m for dredging. I’m for renourishing the beach, bringing in, dredging the sand, bringing it in, putting it on our beach.” She spoke of the “scary feeling” of hurricanes crumbling dunes and jeopardizing properties. “We have the next 50 years of maintenance. We’d be crazy to not be for it.”

Cooley, who’d been part of the discussions about the project, rested on the Corps’ expertise and history of beach engineering. “They know what they’re doing,” he said. That’s true, up to a point: the Corps also has a history of cataclysmic failures, not least of them the one that, in the 60s, reengineered the barrier island, including parts of Flagler Beach, in what proved to be a disastrous effort to control the mosquito population. The barrier island community was at the center of a controversial plan two years ago to reverse that engineering. The plan, paid for by the St. Johns River Water Management District, carried through, to the dismay of Flagler Beach residents. “My belief is we follow subject-matter experts and we do what they say,” Cooley said of the renourishment project.

Quinn said he was “kind of in favor,” but said he saw such a project in Westhampton Beach on Long Island, N.Y. “Two years later, all the sand is gone, so maybe we do something different out there,” he said. Quinn was misinformed, and may have misunderstood the way renourishment works: erosion is built into the project, which is why it requires periodic renourishment.

The Westhampton Beach project, on a barrier island almost identical to Flagler Beach’s, was also the subject of a rigorous, peer-reviewed analysis published in the West Palm Beach-based Journal of Coastal Research in 2009, when the analysis summarized the project’s history since 1996, when it started, with a projected 30-year lifespan. The project provides for beachfill placement, dune construction and beachfill renourishment until 2027, the study stated. “Project coastal processes monitoring since 1996 has shown that the shoreline position in the project area has been stable and there has been volumetric growth of the dune field west of the groin field,” the study found. “The 10-year average volumetric loss in the project area of 180,000 cubic yards per year is very similar to the 759,000 cubic yards (190,000 cubic yards per year) renourishment volume placed in 2005 after a four-year renourishment cycle…. Good stewardship of the beach and dune system will allow the Westhampton Interim Project to be maintained and provide the storm damage reduction purposes for which it was designed.”

The last renourishment, a $22.3 million project that was 65 percent federally funded, was completed less than a year ago. “Time and time again, the Army Corps of Engineers has delivered for NY-1,” U.S. Rep. Lee Zeldin, who represents that district, said at the time, “despite those who have sought to shamefully attack them for political gain.”

The Flagler Beach candidates were also asked a covid-inspired question: “Where do you stand on personal freedoms versus public safety, and how do you feel city government is doing in this regard?” The city approved a mask mandate. It had also approved of the health department’s closing of the beach for a few weeks in the initial surge of the pandemic last spring. Late last month two residents were arrested at a Flagler Beach City Commission meeting, for trespassing, after refusing to wear masks or leave the room when asked.

Johnston found a way to skirt the civil-liberties-angle of the question by focusing exclusively on public safety, favoring community policing and speaking of residents’ sense of safety in their homes. Intentionally or not, she did not pick up on the more pandemic-tinted part of the question.

Cooley took it on more directly. ‘One of our number one jobs is to keep our citizens safe,” he said. “If we have a hurricane coming, we’re going to tell you to evacuate. You have personal choice. You can stay. But it’s also our job to keep you safe. You all know, we’ve all seen that when this pandemic was coming, and we were watching town after town start closing beaches, mind you this is in the middle of spring break when we are very, very busy, we have a giant influx of visitors coming to town, I was one of the advocates to say: we need to stop this, the partying the hanging out on the beach, the visitors. We have to protect our citizens.” He has since had little patience for the sort of misinformation and scaremongering that has equated public safety measures with repression. But he reminded the audience that seat belts and evacuations are also safety measures, and between one choice and another, he said, he’d fall on the side of safety.

Carney spoke more along the lines of Johnston’s understanding of the question. She spoke of her involvement in the city’s beach management plan, when discussions of personal freedom came up. “It’s a public beach,” she said. ‘We had to look at access to the beach and what the city would do to provide access, and are we required to provide 51 crossovers at the beach.” But rather than discuss the pandemic, she recalled discussions on the commission about bonfires, and how that could hamper sea turtles at nesting time. The decisions are tough to make, “but somebody has to make them,” she said. To Quinn, “public safety should come first.”

The perennial question about police and fire service consolidation with the county was again raised Tuesday evening (“I knew this would be a question that came up,” Johnston said). But there’s no quickest way for a city candidate to lose an election race if he or she were to speak in favor of consolidation, and none of the candidates did so.

Carney who has previously been critical of fire department spending on firetrucks, said she is “not opposed to fire and safety. My problem with it is the way they presented it. And when I talked about propaganda when I opened tonight, I was led into a meeting where I thought I was going to be voting on fire equipment, and it ended up being a $650,000 fire truck. As a commissioner, I felt that I was blindsided. I do not believe all the data was presented. I don’t like the way a lot of data is presented. But it is not my will to go above anybody or any citizens’ request or need for fire safety.”

watchdog says

In my opinion, the counties future is in trouble if another Johnston gets there tentacles wrapped around this one. Flagler’s very on “Yellowstone” cable show.

BMW says

Keep Ms. Carney and her talk of “Propaganda” out of anything to do with Flagler Beach’s government. She is mean spirited, vindictive and our town has too much to do to take a step backward. And, if Harrington is her ally, that’s a team we can do without. If Ms. Carney was a viable candidate, with her years of service on the Commission, she should have a litany of accomplishments to cite as opposed to all of her “Propaganda” speak.