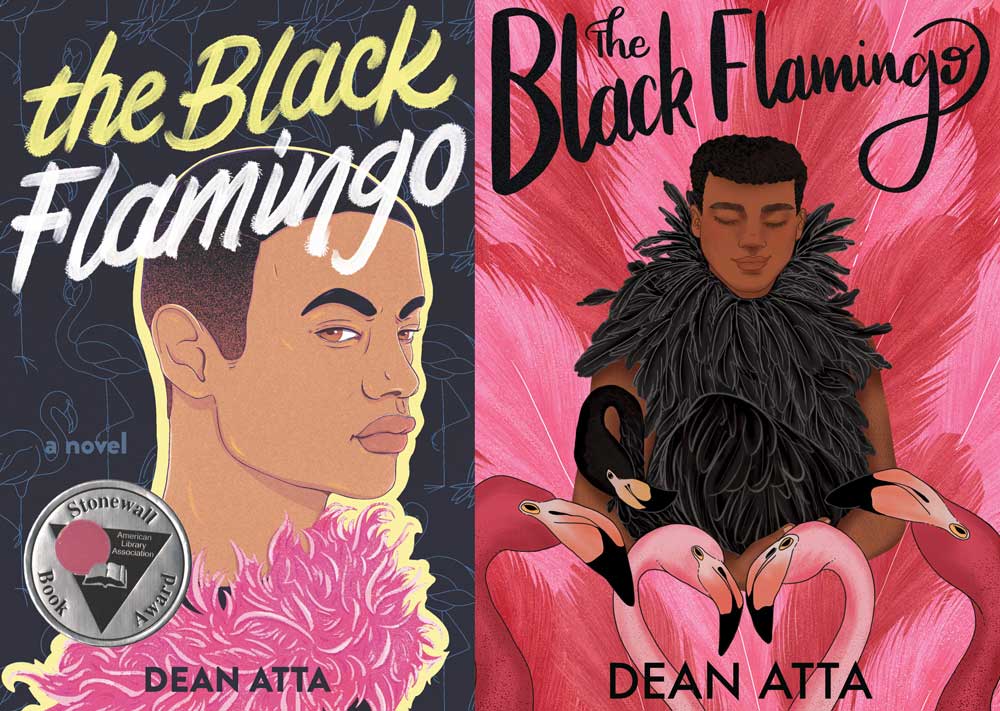

Dean Atta’s The Black Flamingo (Blazer and Bray/HarperCollins, 2020) is among the 22 books so far this school year that a trio of individuals have sought to ban from high school library shelves. A joint committee of Flagler Palm Coast and Matanzas high school faculty members and parent representatives meets today at 3 p.m. to discuss The Black Flamingo and decide whether to retain it or ban it. (The committee last met two weeks ago and voted to retain Jennifer Mathieu’s The Truth About Alice.) The meeting, open to the public but not to public participation, is at the Government Services Building, 1769 East Moody Boulevard, Bunnell, in Room 3A on the third floor. The following review is presented as a guide.

![]()

Dean Atta’s The Black Flamingo is one of those novels that, beside leaving you moved and joyful and just plain bonkers for the writer’s grit and style, makes you wonder how it could possibly end up on anyone’s shit list. I could understand somebody not getting all Bianca Del Rio about it. It’s all in verse, after all. But who can be so crabby, so dismally sad and dense as to want to ban from school library shelves the story of a young man discovering himself through supportive friends, a loving family, the occasional betrayal, through theater and poetry, through school’s and life’s cruelties and exclusions and through more than a few unexpected redemptions?

Dean Atta’s The Black Flamingo is one of those novels that, beside leaving you moved and joyful and just plain bonkers for the writer’s grit and style, makes you wonder how it could possibly end up on anyone’s shit list. I could understand somebody not getting all Bianca Del Rio about it. It’s all in verse, after all. But who can be so crabby, so dismally sad and dense as to want to ban from school library shelves the story of a young man discovering himself through supportive friends, a loving family, the occasional betrayal, through theater and poetry, through school’s and life’s cruelties and exclusions and through more than a few unexpected redemptions?

Well, somebody can and has. Somebody–one person, really–wants this book that Time Magazine called one of the 100 best Young Adult books of all time removed from library shelves at Matanzas and Flagler Palm Coast high schools.

I’ll go on a very short limb here and venture that the person who filed the challenges (who doesn’t even have children in school) hasn’t read the book. Book-burners generally don’t, though in this case it’s just too obvious because even in the hands of a second grader (or in those of Bill Bennett), the book would only leave glitter marks: the language is that pure, that sparkly and free of anything that might get bleeped on broadcast TV.

The one exception is the scatological reference I dropped in my opining line. It appears five times in the book, three times as the sort of harmless exclamation you might hear yourself say in church when you suddenly remember that you didn’t log out of Pornhub before leaving children and husband to their Sunday snores. Actually, “Shit! Why did I say that so loudly?” is one of those five instances in Flamingo, as the protagonist just realizes he’s asked another boy out in front of a whole bunch of schoolmates.

There goes the raised eyebrow. A boy asking another boy out, at school? But would you have raised that eyebrow had the line been about the boy asking out a girl? Of course not. Even if those two were in second grade (the protagonist is in high school). Your eyes would have glazed right over that line as if it were as unremarkable as NFL hulks molesting each other’s butts after every play on network TV.

Now we’re getting into the why of this desired ban. It’s not the words. It’s not the explicit scenes, or even the suggestion of explicit scenes, because there aren’t any. It’s simply who the character is, what Dean Atta portrays, and the sense of freedom with which he portrays it.

The Black Flamingo is a coming-of-age novel in verse about Mike Angeli, a boy of Jamaican and Cypriot descent growing up gay and black in London, going to college in Brighton–“the gay capital of the UK”–and discovering drag as his “rebirth,” his “liberation” and “ancestry,” and whose dreadlocks get him stereotypically mistaken by the incidental idiot for Bob Marley or a drug dealer. So there you have it: the trifecta of book-banners’ fixations: gay, black, drag. It mustn’t help that, like his creator, Mike didn’t even have the courtesy to be American, where he could at least get a good beating at cops’ hand, though one of the more dispiriting scenes in the book describes Mike in the car as his uncle is moving him to college, getting pulled over for no other reason than the suspicion at a pair of blacks in a nice car. Atta gives the uncle a voice:

Pulling me over

for driving a nice car.

This isn’t what I wanted

for your moving day

but this is what it’s like

to be black in this country

or anywhere in the world.

They interrupt our joy.

Our history. Our progress.

They know they can’t

stop us unless they kill us

but they can’t kill us all,

so you’re living your life

and suddenly interrupted

by white fear or suspicion.

(Gov. DeSantis must be having a seizure somewhere.) A few of Atta’s poems get a bit didactic like that, especially as the book wears on, but the heavy-handedness is rare. It’s easily overwhelmed by a flip side of depths of feelings subtly observed, as when Mike is visiting his grandfather in Cyprus, his traditional grandfather with whom he’s never broached the subject of his well-emerging gayness. The TV news has been reporting on the landing of an unusual black flamingo on the island:

The black flamingo is on the news again.

I pick the dining chair facing the TV.

Grandad asks,

“Why does it matter if he’s black?”

Adding, “The other flamingos don’t care.”

And I am certain what he’s saying is:

“I love you.”

Very much like Mike, Atta is a British poet of Jamaican and Cypriot descent who grew up black and gay in London and went to college in Brighton, where he was president of the African Caribbean and Asian Society, graduating into his own world of poetry and drag.

It’s tempting to read The Black Flamingo as autofiction, the genre very much in vogue that erases boundaries between autobiography and fiction. Some of its most celebrated practitioners–Karl Ove Knausgaard and Annie Ernaux, who just won the Nobel for literature–reject the label, as does Atta, who told an interviewer that the book is mostly fiction.

What does it matter, anyway, whether the fiction is “based on a true story” or not? The greater the fiction, the truer, whether it is factual in our pedestrian, as-it-happened sense or not. He also told an interviewer that the book started as that one poem, the one about the black flamingo, and grew to novel length from there. If so, the inspiration is as telling as the simple recurring message at the heart of the book. It’s really about love, including and especially love of self, which the black flamingo comes to represent as Mike’s drag persona: “He is me, who I have been,/ who I am, who I hope to become./ Someone fabulous, wild, and strong./ With or without a costume on.” Exuberance outplays doom on almost every page.

Mike is just shy of 6 years old when the book begins, and well into college when it ends. He gets Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles for his seventh birthday despite asking for a Barbie. He’s bullied, gets in a fight, gets transferred to a Catholic school, where classmates become surprisingly accepting, most of them. Some leave abominable little anonymous notes from Leviticus in his book bag. But there’s Daisy, the girl who becomes his best friend and part of his family. Their friendship almost breaks when she reveals her fear of being taken for a lesbian and he calls her a homophobe. The resolution is a bit forced: it turns out Daisy was repressing her own sexuality all along.

Mike’s crushes course through the first two-thirds of the book with delicate tension, never crossing into anything overt either for Mike or for the reader, because so much at that age is so bewilderingly tentative and unspoken: “I’m thinking about Rowan. / I’m thinking about Kieran. / I’m thinking about going to Hell when I die / and a living Hell on Earth.”

When he’s 16 (his mother has given him condoms, imploring him to be careful), he downloads an app and meets an older man in a cemetery. Is this where the book crosses a line? Not at all. The man drugs him. Mike wakes up disheveled. We don’t know–he doesn’t know–what happened, though that seems a bit naive. All he knows is that it’s best to delete the app and leave anonymous meets for others and the thread is improbably dropped.

When he does end up losing his virginity, consciously, the act is barely implied by a repetitive foreplay of words in innocent questions and answers, not acts. it’s ingenuous and warm, and it makes you want to hug them both. Incidentally, the longest hug Mike had was 19 seconds, he tells us early on.

The last third of the book loses a bit of its tautness as Mike’s more assertive adulthood takes over. The verse sounds almost like a drag clinic here and there (I read the book by way of Atta’s own intimate narration). It doesn’t diminish the book’s effect, the way Mike seems unconsciously to be a guide through the shoals of adolescence and young adulthood, of race and sexuality, of family and friendship, the way Atta sums it all up in a hymn of a poem about “What It’s Like to be a Black Drag Artist (for those of you who aren’t), ending after trills of humor and jubilation with an identity reclaimed:

It’s Afrofuturism. It’s Afrocentrism. It’s black,

black, blackity-black. It’s batty bwoy, sissy.

It’s queer, gay, and faggy. It’s yours

and it’s yours. It’s mine. It’s time to step

out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

![]()

The following questions in bold are reproduced here exactly as they appear on the Flagler County school district’s school-based Review Questionnaire for media advisory committees taking up book challenges–or attempts to ban books–at the school level. Committees fill in their answers as they reach a decision on each challenged book, after a lengthy committee discussion. The answers below are provided as an amendment to the preceding review, in the more focused context of the district’s question, and are of course only the reviewer’s own–in this case, FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam. Committees may reach vastly different conclusions. Those will be appended below, once they are issued.

Title: The Black Flamingo.

Author or editor: Dean Atta.

Publisher: HarperCollins.

Basis of objection: “Materials contain pornography, Materials are not appropriate for the age of student.”

1. What is the purpose, theme or message of the material?

The novel is a road map shaded in hope and resilience about how to grow up black, gay and self-affirming in an environment that may not be understanding or supporting–but isn’t hopelessly without the ability to learn to be both.

2. Does the material support and/or enrich the curriculum?

While it’s unlikely that the book would make it on any English syllabus in these fearful and intellectually impoverishing times, it easily could–not for its theme (which risks unfairly pigeon-holing the book as a single-subject or single-purpose novel), but for its form and style. By pulling off a book in verse and making it as accessible as a picture book (Atta’s style is quite visual), the author breaks down some readers’ resistance to poetry and shows its possibilities as a form that doesn’t belong only to the Eliots and Dickinsons: if you want to make a student’s path to Shakespeare’s sonnets less daunting, have the student read Atta first. (The themes between Flamingo and the sonnets are closer than they appear anyway.)

3. Does the material stimulate growth in factual knowledge, literary appreciation, aesthetic values,and/or ethical values?

The book is profoundly, at times annoyingly, ethical: it does not engage with too many gray areas and risks being dogmatically P.C. here and there. That’s more a literary than a ethical failing of course. But as literature, it invites the reader to rediscover the power of poetry in its more conversational, less intimidating sense, the way it was read and heard, say, in ancient times. (Intentionally or not, Atta is harking back to his very ancient Greek-Cypriot heritage.) So the book works aesthetically and ethically. It is not designed to impart facts per se, other than the obvious: homosexuality is a fact, and much as it should pain anyone to have to say it in a time and place where it is not as obvious as it should be, homosexuals are no less human than others. Even (gasp) black homosexuals.

4. Does the material enable students to make intelligent judgments in their daily lives?

Three years ago I reported on the trial of Victor Williams, 43 at the time, who was accused of drugging and raping a 16-year-old Palm Coast boy after the boy and Williams met on the Grindr app. A pivotal scene in The Black Flamingo takes place when Mike, the protagonist, turns 16, downloads an app, and uses it to meet a man considerably older, in a cemetery, where the man proceeds to drug Mike, who passes out. We don;t know what happens to him, though the suggestion seems obvious. Mike, oddly less traumatized than he should have been, nevertheless uses the experience to get rid of the app and stay away from stranger meets of the kind: a wise choice and a useful message for people at both ends of these apps: Victor Williams is serving 10 years in prison.

5. Does the title offer an opportunity to understand more of the human condition?

Very much so, but not for its more obvious reasons. While The Black Flamingo is typically presented as a young adult book by and for young, minority gay individuals (that roadmap I mentioned earlier), that again is unfairly limiting. The book speaks just as powerfully to the white heteros who make life so miserable for those unlike them–the white heteros who cram their sexuality down everybody’s throats at every turn in our dogmatically hetero public culture, but who turn around and accuse the first openly gay person to be cramming down his or her sexuality down their throat. The Black Flamingo‘s gently humane story can and should be read by those who either don’t understand or don’t accept homosexuality. It’ll open their mind without offending it.

6. Does the material offer an opportunity to better understand an appreciate the aspirations, achievements and history of diverse groups of people?

Yes. I referred in my review to the protagonist hitting the trifecta: gay, black, drag (and non-American, immigrant in this case). The title alone is symbolic of a book drenched in diversity.

CONTENT

1. Is the content timely and/or relevant?

Florida in particular and the United States in general is going through a period of blowback against the LGBTQ movement and minority cultures, black cultures (the plural is essential, as ought to be the plural of black histories) especially. So yes, the content is timely and relevant.

2. Is the subject matter of importance to the students served?

Considering that, according to the Centers for Disease Control, “43% of transgender youth have been bullied on school property. 29% of transgender youth, 21% of gay and lesbian youth and 22% of bisexual youth have attempted suicide,” then yes, the subject matter is of great importance to the students served, particularly those students who would rather not be served.

3. Is the writing of high quality?

Dean Atta is a wonderful writer. Some didacticism aside, the style is light, at times very inventive, never dull, as in this set of verse that flits from puns to surprises to baffling similes to pathos wrapped in fun: “I come from griots, grandmothers,/ and herstory tellers. I come from / published words and strangers’ smiles./ I come from my own pen but I see / people torn apart like paper, each a story / or poem that never made it into a book.” (Page 246)

4. Does the material have readability and popular appeal?

Readability, certainly: once you start you’d better forget about your commitments for the following three hours. But popular appeal? That’s a loaded question in a soon-to-be open carry state, where it’s been open season on LGBTQ people and people of color.

5. Does the material come from a reputable publisher/producer?

The book was first published in 2019 in Britain by Hodder and Stroughton, one of Britain’s oldest publishers (established in the 1840s or 1860s, depending on how you date it), with tantalizing precedents of publishing books considered controversial in their time (Alice in Wonderland). It’s published Winston Churchill, John le Carre and Enid Blyton, among innumerable others, and was acquired by Hachette, the mega-publisher. In the United States, The Black Flamingo was published in 2020 by Blazer and Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins, one of the five largest publishing houses in the country. Its parent company is Rupert Murdoch of News Corp, home of Fox News, which has fueled the fires of book-burning over the past two years.

6. If presented as factual, is the content accurate?

The book is a novel, though nothing told lacks verisimilitude or a foundation in fact.

7. If the text is informational, is the text comprehensive?

It is a how-to book only in the literary sense that all coming-of-age novels from The Odyssey to The Magic Mountain are informational.

APPROPRIATENESS

1. Does the material take in consideration the students’ varied interests, abilities and/or maturity levels?

Yes. Dean Atta presents a variety of perspectives, all of which can speak directly to students in their middle and high school years, though adults would find the book just as insightful. The book’s style is entirely unpretentious, seeking to connect with readers, not knock them over the head with impenetrable style. Impenetrable hacks like me could learn from Atta.

2. Does the material help provide any of the following:

- A resource that represents a level of difficulty accessible to readers at the school?

- Diversity of appeal?

- Representation of diverse points of view?

Yes to all three of these questions, for the same reasons explained in the previous question.

3. Does the material help to provide representation for various religious, ethnic, and/or cultural groups and the contribution of these groups to American heritage?

Religious, ethnic and cultural groups, yes: The Black Flaming is set in contemporary England, a very diverse country with its own racial and ethnic tensions. There’s also an element of religious tensions in the book, when Mike, the protagonist, is targeted with anonymous notes cribbed from Leviticus, threatening him with doom and death over his homosexuality. The notes end up being written by a girl whose brother comes out as gay, and who later apologizes to Mike.

4. Does this material provide representation to students based on race, color, religion, sex, gender, age, marital status, sexual orientation, disability, political or religious beliefs, national or ethnic origin, or genetic information?

Yes to most of the above: Unmentioned in the review is the quiet portrayal of Mike’s mother, a single mother who seems to have a lot in common with Maya Angelou (there are five references to Maya Angelou in the novel, including a full poem devoted to her). Political beliefs and disability (other than the sort of intellectual and emotional disability that makes people bigoted) play no role here, but there are intersections between national origin and living in a different, dominant culture, and of course color, sex, sexual orientation and gender play a central role, which is really why we’re here, addressing this in a debasing, inquisitorial book challenge, isn’t it?

5. In a Yes or No answer only, do you feel the material has a purpose for a school library collection?

Yes.

Comments specific to the objection:

The single objection was filed by Terri McDonald, but plagiarized from a national website that provides book-burners everywhere with a template to submit to their respective school districts. So it isn’t really Terri’s objection. It’s the same objection copied and pasted word for word, page for page, from that BookLook.info website’s “report” on The Black Flamingo. The objection reads: “Materials contain pornography, Materials are not appropriate for the age of student.”

That it contains pornography is demonstrably false by any definition of the word. There is not a single scene where so much as the outline of a cock even appears on a Speedo, though there is a delightful scene when Mike’s family buys him a Speedo before their trip to Cyprus, and Mike pretends to be offended. The scene in the graveyard literally cuts from when Mike and the other man are touching each other (without any sexual details), to when Mike wakes up, disheveled. Not appropriate for the age of students? Again: there’s nothing “inappropriate” in the book, unless one considers two boys kissing inappropriate. If the objection is to that, while no such objection about a boy and a girl kissing would be filed (otherwise we’d be without half the books in our libraries), then this objection is not about “inappropriateness.” It’s about bigotry, which is not permissible in Flagler schools. In essence, the objection is itself self-disqualifying on grounds of overt prejudice.

Additional comments:

None.

Recommendation (retain, remove, other):

Retain in middle and high schools.

![]()

A few other reviews of The Black Flamingo:

- Kirkus

- Publishers Weekly (starred)

- The Guardian

- Goodreads

- Dean Atta talks to Nadine Aisha Jassat about his book Black Flamingo (video)

- Dean Atta on Brent Locked In (video)

![]()

Janet Sullivan says

Thank you for the

extraordinary amount of time you spent on this. Very educational for the residents.

The dude says

It’s funny how the ones screaming about burning books the loudest also have no real skin in the game. These are the folks who end up on the HOA boards. Old, angry, and anxious to rule the lives of all thier neighbors.

What Else Is New says

Only cowards ban books. One wonders how those who remain uninformed can function with their ignorance. I consider our Governor in the mix.

Pierre Tristam says

Thank you Janet, but it’s a fraction of the amount of time our educators are having to spend on this, at the expense of their work, their students and their private lives, all to answer the drive-by “challenge” of a single book-burner who didn’t even have the integrity to file her own challenge: she plagiarized it from a national website run for those mums for bigotry vigilantes. That’s the real shame here. These subliterate goons are playing the system, and state government is now their amen corner.

Michael Cocchiola says

If the school committee bans it, I will have a very poor opinion of the schools and their commitment to the education of our young people.

Laurel says

To the Mommies of Illiteracy: If you think that teenagers don’t know about sex, don’t know about gays and are somehow going to turn overnight into someone other than who they really are, then you need some education yourselves. Teenagers are way ahead of you.

To reference to, and expose teens to Maya Angelou is worth the book alone.

Candi says

In the first paragraph of this article you incorrectly state the book title as “The Pink Flamingo.” The correct title is “The Black Flamingo.”

FlaglerLive says

Thank you.

don miller says

how did this book get to this point of scrutiny anyway? It is taking up space that should be for renown authors with a pedigree. What’s next arguing the values of KS indian sex books with pictures? Or how to access HIV prep? this book is just persuasion propaganda and not of paramount literary importance. yes, it is me again. Count on me to counter balance the who cares anything goes gang.