The beaches are eroding, the dunes are disappearing, properties are becoming more vulnerable. None of that is new. But for Flagler County, quantifying it is new, and quantifying the full cost of slowing that erosion is newer still.

Flagler County Commissioners heard that cost today: $6.3 million a year, in today’s dollars, year after year. That’s among the more reasonable options. It’s money the county does not have. If it is to secure it, it would have to come up with new revenue sources, either from tourism dollars, from targeted taxing districts, from its own general fund, or from state and federal sources, and almost certainly, a combination of all those sources.

And yet it isn’t a colossal cost. $6.3 million a year is less, far less, than what the county spends on recreation, transportation, fire and law enforcement, or interest on its debts, for example. But it’s nowhere in the budget.

As befits any analysis of oceanic, climatic and coastal issues, there was a lot to digest for County Commissioners and many others in attendance Monday in a seminal three-hour workshop on the uncertain and so far largely unplanned future of the county’s increasingly at-risk shoreline

The workshop was designed to reduce some of that uncertainty. Commissioners were presented with reams of data and options, and asked to give direction as to what to do next–not just direction to the county administration, but to cities, to homeowner associations, to residents at large, all of whom, commissioners concluded, would have to be part of the solution.

“There’s other counties in the state that have been doing this for years and years and have a dedicated fund that does all this,” Hansen said. “That’s what we don’t have. We’d have to get from here to there while minimizing the pain.”

The workshop was not about how to get from here to there, but about the mechanics of that distance: how much work the beaches will need, how much it’ll cost, how the pain, like sand leavening new dunes, might be spread.

The county’s 18 miles of shoreline were significantly damaged by hurricanes Matthew in 2016, Irma in 2017, and Dorian in 2019. The county restored 11 miles’ worth, though those dunes have eroded since.

There are three large projects ahead: the much-written about $25.8 million U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project that would rebuild 2.6 miles of dunes in Flagler Beach and a $10.85 million state-funded project that would rebuild 2.8 miles. Both are funded. The county also received $3.8 million from the state Department of Environmental Protection to restore the dunes at Gamble Rogers State Park. The Federal Emergency Management Administration also provided $2 million, with a $339,000 match from the county and an equal match from the state that would restore 2 miles at the north end of the county.

Beyond that, “Flagler County does not have a long-term plan, and we are here to discuss that,” Faith al-Khatib, the county’s engineer, said.

The county hired Jacksonville-based Olsen Associates Coastal Engineering to conduct a long-term study and include costs ahead. That study, a foundation for a beach-management plan but the plan itself, formed the core of today’s presentation.

“Of the 40-some counties that have beachfront on them, we’re the only county that really doesn’t have a long term plan. And that’s not our fault,” Hansen said. “We have never needed one. We have been spared the ravages of hurricanes here in Flagler County.”

Beach-management plans, of course, are not predicated on whether a county is impacted by hurricanes or not: coastal counties typically have such plans regardless. As Hansen himself said, other counties have funding mechanisms in place already for their management plan–because they planned ahead. Flagler has been behind on that score, with storms rather than enlightened leadership forcing the issue. Leadership on the issue came around with the storms.

“Unfortunately,” Hansen continued, “starting with Matthew and Irma now we’ve been whacked pretty good and we’ve lost our dunes. So that’s kind of the background of why we’re starting down this road because we have to, or we’re going to lose our beach.”

Creed had some startling facts about the physical condition of the county’s dunes–the first such hard data ever presented to the commission. For example, the dune crests, or “summits,” in lay terms, are still high in most parts of the county. But they have moved inland. The average crest is 18 to 19 feet. But the crest drops significantly at the north end of the county.

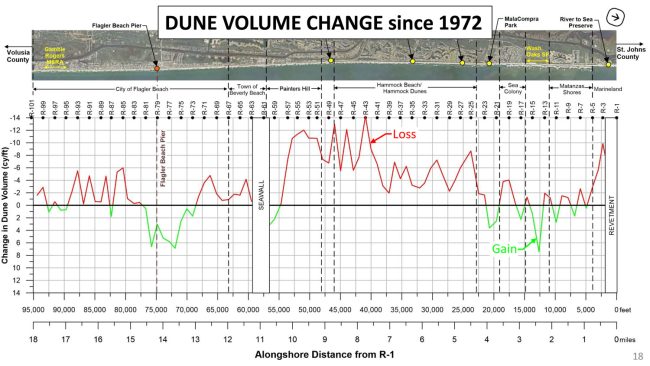

Since 1972, the year when the state installed instruments measuring dune heights at 1,000-foot intervals, about half the dunes in the county have lost height–not at the north end of the county, but in the Hammock, Painters Hill and at the south end of Flagler Beach, south of State Road 100. More critically: dune volume has decreased almost everywhere in the county, especially in those same places where dune heights have fallen. Dune volume is as important if not more so than dune height: the combination stops water intrusion. (See all graphs and data in the presentation embedded below.)

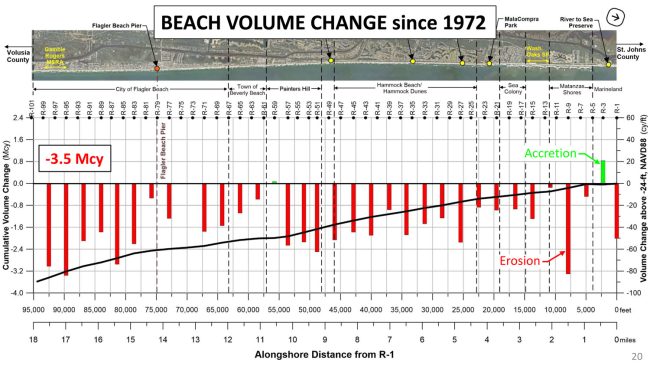

One more wrinkle: dunes can be high and thick, but that can be irrelevant if the beach itself is bare. “It is the beach that protects your dunes,” Creed said. “If you don’t have a healthy beach, you can put all the sand you want to in the dunes, but if it doesn’t have the fronting protective beach, it is very vulnerable, and it will just not last.” In that respect, beach volume in Flagler, all along the shore (with a minor exception in Marineland), has experienced sharp erosion since 1972–or 3.5 million cubic yards of sand in that span. And 1.1 million cubic yards were lost just in the last 10 years, pointing to an alarming acceleration and underscoring a point Creed did not make: the sea is rising, inexorably.

Bottom line: there’s been critical erosion in all of Flagler Beach, most of Painters Hill, and in Marineland. Those areas would be more eligible for state funding (through the state’s beach program) and possibly for extensions of Army Corps of Engineers projects such as the one pending in Flagler Beach.

“We’ve seen erosion rates over the last 50 years and there’s no reason to believe that those will change,” Creed said. “However, the question moving forward is: how high will they be? Will it be like the last 10 years? Or will it be like the previous 40 years? And it could be some combination of the two or some mix of the two. So that’s important decision-making moving forward in terms of scoping projects and how much sands should we plan for, particularly when we start looking for money.”

It’s not as simple as rebuilding beaches simply by dumping sand. Especially at the north end of the county, there are nearshore coquina rock formations that provide protected habitat for endangered species, so there are strict constraints on what can be done to the beach there. If beach reconstruction causes damage to the habitats, the damage must be mitigated. Mitigating those impacts can be very costly–between $1.5 and $4 million an acre. But beach management can also go lighter in more sensitive areas like that coquina-rock shore: smaller dunes, replenished at more frequent intervals.

So depending on the project, the source of the funding and the location of the dune reconstruction, the size of the projected dunes would range from 6 to 44 cubic yards per foot. Creed provided six options, from least impactful dumping of sand to most impactful. The cost increases as sand volume increases. Every dune will need to be maintained in future, in some cases as frequently as every three years, or as long as every 11 years.

The county has secured an offshore borrow area some 9 miles off. The area has millions of cubic yards of sand potentially available, though it’s not limitless, and permits must still be secured to access more sand. There are land-based quarries that can produce sand, but it’s much more expensive: $55 per cubic yard compared to $15 for sand taken offshore.

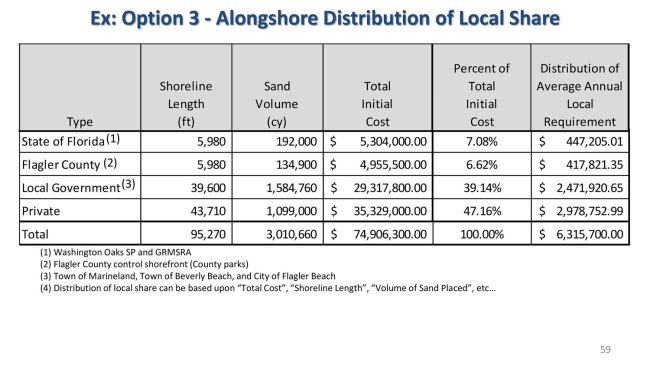

Creed’s bottom-line costs were sobering: $97 million when the whole shoreline was considered, and a mixture of off-shore and on-shore sand was used to rebuild dunes–just for one “event.” Removing federal and state credits, that reduces the cost. But taking a middle-of-the-road option among six options, and annualized over 50 years, “the local community, local being all of Flagler County and all stakeholders involved,” Creed said, “is between $5.5 and $7 million per year. This is not out of line with [where] other communities are.” That’s how he reached the more precise, amortized number: $6.3 million.

But while there is new state funding for beach management, Olsen had a surprising revelation for the commissioners: “The resilient Florida program money will not be used on the beaches and dunes in the state of Florida,” he said. “I’ve confirmed this just on Friday with the person leading this program. So moving forward in a beach management approach from the state of Florida funding is going to be best secured through the beach management program for that aspect of the improvements made along the shoreline.” Simply adding sand to the beach will also not be something FEMA will pay for.

Beaches don’t respect political boundaries, so piecemeal management doesn’t work. Management must be comprehensive even if funding can be (and by necessity must be) more fragmentary: no single source can pay for it all. So Creed offered up an option where the annual cost would be split between cities (Beverly Beach, Flagler Beach, Marineland), the county, the state, and private taxpayers, broken down by frontage: who owns what along the shore. That yields heavier costs for the cities than for the county, and the heaviest cost share, $3 million, for private property owners. The county could devise various funding mechanisms, whether through its tourism dollars, through taxing districts, through its general fund, and so on.

“It will be upon the county to decide,” Creed said. “What are the next steps for you?”

For starters, Flagler Beach City Commissioner Jane Mealy objected to the list of cities considered “stakeholders.”

“I think that Palm Coast needs to be included in that stakeholder group,” Mealy said, “because it’s mostly people from Palm Coast who come to use the beaches.” She was also interested in seeing an extension of the corps’ project north of the pier.

The corps’ study that led to that project along 2.6 miles of Flagler Beach’s shore took 10 years: it started in 2004. It was completed in 2014. It has yet to be implemented. In that time span, other counties have seen their beaches renourished.

“A lot of folks don’t realize, the Corps has about 20, 23, 24 beaches in the state of Florida that gets sand put on them every so many years,” Jason Harrah, the Corps’ project manager, said. “The majority of the beaches around the coast of Florida are manmade and folks don’t realize that. For the Corps, our mission is to protect property, protect life, protect infrastructure.”

He too had news: “a new study,” and a potential extension of the federal portion of the Corps’ beach management–not just renourishment and dunes is possible. “We shouldn’t have 10 years to complete a study,” he said. It would take three years and cost $3 million. (Al-Khatib said it could be a waste of money to conduct a study when the conclusion is already clear.)

The process starts with the local government making the request and identifying the beaches in question. The local government must also be willing to provide all necessary easements–and proper parking access to the beaches that would be rebuilt. That’s not a given on several stretches of Flagler beaches, though Commissioner Andy Dance said if public access is a condition, then it must be provided. Next, Congress must approve the study through the annual Water Resource Development Act. Then the federal dollar appropriation must be secured. Don;t expect any of this to happen fast.

The area with the likeliest chance, based on Harrah’s projection today, is in Painters Hill (the area south of the Flagler Beach pier is already set for reconstruction.) “We know the damages have increased drastically,” Harrah said.

So what will the county do?

Hansen proposed hiring a second county engineer to focus on beach issues. “I have been asking for this position for the last 10 years,” al-Khatib said.

Some commissioners spoke of drafting the necessary documents to get additional studies completed for the extension of the Corps’ projects, but there was no clear direction on that score. Commissioners will wait for the Olsen study to be finalized.

Several residents–property owners–addressed the commission, either to support the study, and more pointedly, to not let the Olsen study or the county’s long-term beach management plan mask immediate needs.

One resident urged some attention to rebuilding dunes by Sea Colony (a “band aid” fix is in the works there, Hansen said), and a broader approach to “stakeholders” than just shoreline property owners, if the county was intending to create taxing districts. Others explicitly spoke in support of the Olsen study. “It is the right thing to do,” Colleen White, a representative of the Hammock Dunes Community Association, said. Her community includes 2.5 miles of beach front and some 1,200 residences, and worked with Olden Associates previously. The association is conducting some of its own repairs based on those findings.

“We’re in a critical need. Before the nor’easter hit, I think we were in a position where we could take a hit,” Jim Ulsamer, who represents the Ocean Hammock Property Owners Association, said. “Now we’re not.” He was referring to last year’s storm, which he said took out more sand than in 16 years of storms. “So while this project, the long term project, looks like it is going to take a while to implement, we need something to be done now. So we’re willing to meet with the county as we have always in the past and do our share, and help get this moving.”

A resident raised one of the most important points of the afternoon about the estimated long-range cost: it does not calculate inflation or rising costs of beach renourishment, even though, notoriously, those costs rise (and have been rising) much faster than inflation over the past decade. “The cost for the basis of our estimate are current market conditions,” Creed said. He said on-shore sand hasn’t seen much of an increase in the last three years.

“This isn’t a problem that’s ever going to go away,” Commission Chairman Joe Mullins said. “This needs to be managed and it needs to be managed ongoing.”

![]()

The Beach Management Study’s Presentation:

Click to access beach-management-study.pdf

Robin says

I was at today’s workshop. My hope is that the Commissioners will pull together to resolve this issue and select a plan. Otherwise what we saw in 2016 WILL happen again. It’s just a matter of when.

Jimbo99 says

Let it go already. The ocean is taking the shoreline naturally. Waste of money & energy to rebuild it. Unfortunately those that have ocean front property, that will erode away, that land is relatively worthless as the process continues. Those that could afford the property must accept that they enjoyed the view, but it’s not on the rest of the nation, the state & county to pick up the tab on this. And that’s not just Flagler county, it’s all of FL, from the Panhandle Gulf of Mexico =>FL Keys => Fernandina Beach. The coastline of the USA isn’t limited to that. Every city & county would need to invest across the board like this to even have a slim chance of saving the coastline every year, and that just isn’t happening.

Enjoy the beach for our lifetimes, the next generation will have it’s beach experiences & perhaps a new shoreline. The new A1A is the next street west of existing A1A, that much is going to happen. eventually that’ll be gone too. That’s what global warming & overpopulation results in. Paying someone millions is pointless waste of resources for the inevitable. This isn’t healthcare for the planet, it’ll be fine, here in some form long after all of us are gone. Science is a good thing when it provides a basis for understanding the process & life cycle. Science is a bad thing when the subject turns to how can we save the coastline like it is in the moment, forever. That’s Fool’s Gold, anyone selling science of a bandaid solution to refill the dunes, when they know the next Northeaster storm or hurricane season is going to take out the last round of dune restoration.

Steve says

Not going to save anything no matter the dollar amount. The Atlantic Ocean will take it.

Deborah Coffey says

You got it! $6.3 million year after year isn’t ever going to stop the ocean. The global warming problem has been ignored for far too long.

Dennis says

That’s a small amount of money to protect the beaches. Heck, it’s only one wasteful bought building the county won’t have to buy! Money used well and not wasted on another “white elephant purchase.”

Fool Me Once says

“And that’s not our fault,” Hansen said.

This comment speaks volumes about the competency of the BOCC and its willingness to be accountable to the taxpayer.

Crusty Old Salt says

Flagler Beach Commissioner Jane Mealy nailed it on the head. A voice of logic and reason. Most of the beach goers that come to Flagler Beach are not residents from the very small population of 5000 or so residents from Flagler Beach. They generally are from Palm Coast , whose population in 2020 was estimated to be 89,000 plus. Today, probably approaches 100,000. Currently, close to 20 times the population of Flagler Beach and that multiplier quickly increasing. The remaining balance of beach goers would be from the surrounding geographic area along with tourists.

If we move forward in this direction, the cost sharing needs to be distributed in a fair and equitable way for all that use the Beach in the City of Flagler Beach. Flagler Beach Commissioners and property owners please stay on top of this issue. Do not be complacent.

Mark says

Well they can either keep their heads in the sand and hope the problem goes away (which it won’t) or start getting the ball rolling now, this month not not down the road. “Next, Congress must approve the study through the annual Water Resource Development Act. Then the federal dollar appropriation must be secured.” not expecting any of our Congressional or State Legislators to do anything unless the County and Towns call them out. The price will only increase the longer the wait.

Sherry says

Those who continue to say that we should do nothing to protect beautiful Flagler Beach should not be visiting and enjoying it, right?

If you are not a part of the solution, “you” are part of the problem!

Jey Stone says

Although each storm and nature’s effects are ultimately unpredictable in degree years of evidence from other management programs have shown to assist in protecting, preserving, managing and provide competent system of restore also whilst having emergency and set funding with surplus carry over. The real issue would be the competency of government officials running it which doesn’t inspire confidence right or wrong. And the nitty details. That said I don’t care either way because even without the beach can change but ain’t going away so. And it’s Public I will access regardless. In conclusion if Flager does move forward Palm Coast must definitely be tapped .

Lance Carroll says

I would think that a majority of visitors to Flagler Beach come from outside Flagler County. Has there been a million dollar study on that subject? Oh wait a minute…just check the new tag reader cameras….

Although, no amount of money or pumped/trucked sand will stop erosion. The reports of 50, 40, 10 yrs of erosion, in my experience, is a moot point. Hurricane Matthew eroded more coastline, in less than twelve hours, than the last 50 yrs total. Hey believers: get your heads out of your asses…..oops, I mean: get your heads out of the sand! Like sands through the hourglass…..

Steve says

What are the chances of charging a fee going across the bridge on 100 like in the hammocks? Residents of flagler beach could purchase a yearly pass while tourists chargd some fees. I would think that would help with dune costs but, don’t know how much or the legal leaps

Misty says

Why should residents who live nowhere near the coastline have to subsidize multimillion dollar beach front properties. Its the same concepts with FEMA flood insurance. Where homeowners that live nowhere near the coastline have to subsidize multimillion dollar beachfront properties. Let those who choose to live in harm’s way pay for its cost.

Marc says

If you use the beach, charge a $10 fee per person. It should not be the county tax payers covering the cost who never go to the beach. Let the people that use the beach pay.