As Flagler County schools today go through their traditional back-to-school rituals—everywhere embraces of the new year, of new classes, of old friends not heard from since the previous hour’s texting—a special celebration took place at Flagler Palm Coast High School that sums up what’s best about the district and its highest-performing students and teachers.

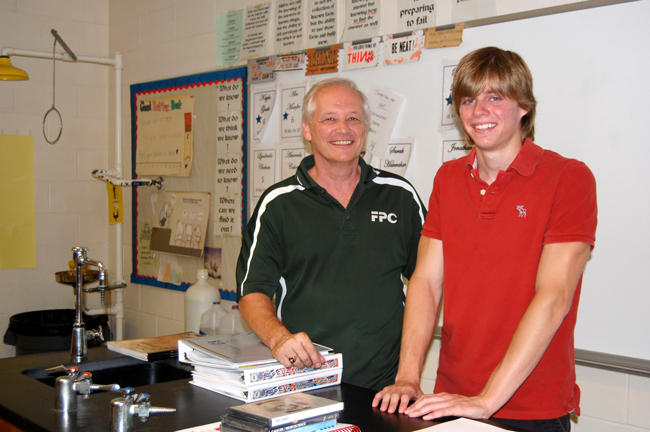

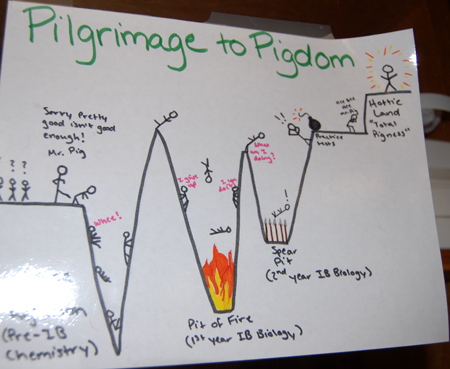

The celebration was in Jim Pignatiello’s class, the teacher everyone there knows as Mr. Pig—fondly so, usually, except when he drives his students to the brink of despair, out there just this side of the impossible. The celebration was for Rowan Littlefield. He’s starting the year as a senior in the International Baccalaureate program. He capped his junior year with a feat no one has ever accomplished in the district before on a science IB exam: Littlefield earned a perfect 7 in his standard-level biology exam, on the IB’s scale of 1-to-7.

There’s been sevens before in language or humanities classes (Adrian Lujo and Cassandra Munoz both scored 7 on their standard Spanish exam last spring, too; both are native Spanish speakers). But never in biology, physics, or chemistry. The breadth of the achievement is difficult to overstate.

“When it comes to thinking and application, our kids just don’t measure up to what most of the rest of the kids in the world are doing,” Pignatiello says. “We hear that every year. When you’re looking at IB, these are the same kids they’re competing against to get these sevens. And you’re looking at a very small percentage of students worldwide who get this.

“I think no matter where it occurs, this is something that we need to celebrate. I mean, football team wins a game—and I’m not trying to put down athletics: I coached for 16 years—but every time somebody wins or does something, you know, it gets headlines in the paper. These kids take these tests once a year. They get one game a year. And they’re competing on the world stage. Not just in our league or in our district. They’re competing on the world stage. You get some of the brightest kids anywhere in any country that we hear about all the time, and they’re holding their own. That’s worth something. That’s worth something.”

Large, laminated cards crowd out more than half the big board in Pignatiello’s class, displaying his biology and chemistry’s students fours and fives. No sixes yet. Littlefield’s is almost literally in a class by himself. His is more of a banner than a card, his 7 more permanently imprinted, since it can’t be bested, rather than stickered on, as other students’ grades are (leaving room for improvement).

“The first thing I had to realize was that I had the ability to kind of go and get the seven,” Littlefield says. “Right after Christmas break I kind of realized I really badly want the seven. I think everyone has to realize that’s what they want. And I absolutely think anyone, everyone is capable of getting a seven. Once you realize that you just have to absolutely commit, dedicate so much time every day, be willing to sacrifice things like hanging out with friends and what not and just study every day. I wanted to, as Mr. Pig always says, distinguish myself from my peers. That’s kind of Mr. Pig’s motto. I try to live by it.” He adds, wryly: “Since he forced it upon us.”

“The biggest thing Mr. Pig told me at the beginning of the year was, there’s a reason why they give you a whole year to study for the test,” Littlefield says. “It’s not, OK, the last month I’m going to cram through the whole thing. You have to take the whole year, study probably like an hour every day, which is what I tried—sometimes a little less, sometimes a little more—but taking the whole year to study for it is basically what it takes. Mr. Pig is basically a great motivator. It’s what I think every teacher should be.”

When Littlefield makes his points, he has a habit of emphatically pointing both his index fingers downward, a double-Aristotelian tic as if subconsciously inspired by Raphael’s “School of Athens” (the famous painting where Plato and Aristotle are walking together, Plato pointing to the heavens and Aristotle, the more scientific, more grounded one, bringing him back to earth with his right hand gesturing toward Earth).

The exam itself wasn’t just a sit-down thing for a couple of hours at the end of the year. It was three exams (three papers) spread over two days, in addition to three lab works done during the year. Each of those lab papers looks like something you’d read in a peer-reviewed science journal, the sort of thing a student has to slave over for weeks, mostly on his own. “You have no idea what they’re going to pull. They’re going to find some type of research that somebody did on some concept somewhere in the world at some point in time,” Pignatiello says. “Nobody knows what it is. You have to analyze it, you have to find out what’s good, you have to find out what’s bad, you have to look for trends, you have to look for errors. In other words you have to truly do science.”

Littlefield heard–and made–all the excuses: “Oh my gosh we didn’t study this in class, I don’t know whatever this concept is.” And looked past them. He doesn’t have much patience for those excuses anymore, the kind that drive parents and teachers nuts until a student decides to bear down and do the work for herself, as a personal commitment–as Littlefield did–as opposed to doing it for a teacher or a parent or even a transcript. “It looks like we’re turning the corner as far as culture goes,” Pignatiello says. “In every high school I’ve taught at, the culture is, and any parent would know this, is to get somebody to want to do their best, what I call they have to get thirsty. There’s too much settling for mediocrity or ‘good enough.’ So it’s finding somebody like Rowan who not only has the ability but has the discipline, perseverance to stick with it, and do what needs to be done to get that kind of score.”

Roger Tangney, the director of the IB program at Flagler Palm Coast High School, compares Littlefield’s achievement to an A-plus at the college level. The grade will earn Littlefield college credit, as will the rest of his IB achievements, if they stay on that high pace. (He’s also earned a 6 in Spanish, though he’s nowhere near a native speaker.) “It’s a major accomplishment both for Rowan individually but also as a salute to Mr. Pig and his efforts, and hopefully it bodes well for the program,” Tangney said.

Last year, Anthony DeAugustino, FPC’s valedictorian, earned about 40 college credits through the IB program. This year, 31 seniors and 40 juniors are in the IB program, which draws students from FPC and Matanzas High School.

Senior year for Littlefield isn’t about to get easier. It’s back to Pigdom all over again.

“The senior year in IB is the total opposite of what culture has ingrained in a lot of students of what your senior year should be,” Pignatiello says. “It is the toughest, the most demanding year on your time and on your effort and on your energy. This is where some kids will backslide. That’s when they’ll have maybe these lofty goals, but they haven’t internalized them. That’s another key concept. You can have all these things that you can say, but if you really internalize them, I think that’s what happened with Rowan around Christmas time, he internalized these goals, they became part of himself, therefore they had meaning at that point, they were authentic. Therefore they became real, then the effort, the conscious effort, the discipline, the persistence, all those habits of mind, habits of success that we all know are important, that’s when they kick in.”

EMPM of palm coast says

God Bless

Jim Guines says

This is a great piece as it tells the dynamics of real interaction that go on between a great teacher and that magically impact on one of his outstanding students.

Bob K says

Congratulations to Mr. Littlefield and Mr. Pignatiello! Awesome job!

Jean says

Congrats Rowan and Mr Pig. All that hard work paid off!! I’m so proud – I’m walking on air.

XOXO,

Mom

Jim Guines says

Mom, you have every right to walk on air as I am very sure that you had a major hand in Rowan’s success. Would be wonderful if every student had great home support and interest of parents.

anonamass says

wow thats awsom!