A Celebration of the life of Jim Guines is scheduled for 11 a.m. July 22, 2025, at St. Thomas Episcopal Church, 5400 Belle Terre Parkway, Palm Coast. All are welcome.

![]()

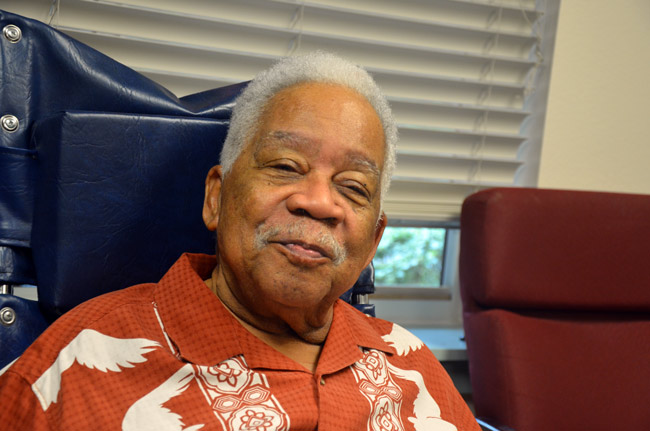

Jim Guines, the forceful, witty, always independent and at times unpredictable member of the Flagler County School Board for 11 years until 2007–the man many had known as Smokin’ Jim for his storied barbecue–died this morning (June 15) at 93 after battling many illnesses and what Lawrence Durrell called “the slow disgracing of the mind.”

A few days ago LaVerne Guines, his wife of 53 years, moved him to Stuart F. Meyer Hospice a short distance from their home in Palm Coast. His caretaker Wendy Watson announced his death on Facebook before dawn today: “Something suddenly woke me up right before 2 am. I heard silence. I jumped up and found my sweet Jim had crossed into his eternal rest. It must have just happened. Oh my sweet stinker Jim. I am forever grateful for your presence in my life. It’s been an honor sir. Rest well my friend.”

Colleen Conklin, who’d served seven of her 24 years on the School Board with him, had at times endured his wrath, especially in the early years, only to become his mentee and, over time, one of his closest friends. She was at his bedside days ago.

“Jim Guines wasn’t just a friend—he was family,” Conklin said today. “His wisdom, unwavering support, and passion for helping children left a deep impression on everyone who knew him. He believed in pushing you to discover your full potential and made you believe anything was possible. I will forever be grateful for his guidance, his laughter, and his love. He made the world better, and I’m lucky to have been part of his and Laverne’s orbit.”

Ten years ago FlaglerLive wrote a profile of Guines on the occasion of a celebration of his life and legacy, and a fundraiser for the Jim and Laverne Guines Scholarship Fundheld at Flagler Palm Coast High School on Nov. 22, 2015, what was to be his last appearance at a major public event. The profile follows.

![]()

Sitting in his wheelchair by himself outside his home in Palm Coast in late-morning sunshine, his arms folded in on themselves and looking without looking at a point in the distance, Jim Guines appears a bit less of the force of wit and penetrating judgments he’d been on the Flagler County School Board for 11 years until 2007, the board member who could demolish opponents with his words and turn benefactor on a dime.

At 83, he’s spent the better part of the last eight years battling one physical setback after another with his wife LaVerne shouldering much of the struggle—surgeries, depression, a stroke. He can no longer walk. He tires. But in conversation, his vitality is intact most of the time. Something on the morning news or an incident from 10 years ago—or 40—can rejuvenate him better than any medicine. He speaks of wanting to write two books. He still goes on cruises. He still talks of working, until LaVerne brings him down to earth.

He was always a force of will. He still is. Next Sunday, Flagler County will show its appreciation, thanks to an idea Howard Holley, the businessman, community leader and one-time political candidate recently had after visiting Guines and finding him in one of his lesser moods. “You like to have somebody get their flowers while they can still smell them,” Holley said of the celebration, “so that was the thinking. I called a few people to see if they concurred, and everyone did.”

The 3 p.m. event at the Flagler Palm Coast High School cafeteria, is a $25-a-person fund-raiser for Guines’s scholarship, which has helped numerous Flagler students attend college. While on the school board, Guines always considered his school board salary improper—he wanted board members, who are paid about $31,000 a year, to serve without pay—and shifted much of his pay to the scholarship fund and other donations. (The Flagler Education Foundation is also a sponsor.)

But it’s mostly a tribute to a rare sort of leader.

The Visible Man

“I’m not the Invisible Man,” Guines said with a twinkle in his voice, referring with irony to Ralph Ellison’s novel. “In my confinement and my illness I get a little depressed, and this gives me joy. I appreciate the concern from my Rotary Club and all these other groups. I’m grateful that some people in the community thought it was worth it.”

Holley has known Guines only a few years, first getting to know him when Holley sought his counsel before deciding to run for the county commission in 2014. Every encounter since has left him with the same impression, how Guines “exemplifies how we want to have impact in our community,” Holley says. “So one of the benefits of this is to say, look at this, and let’s use this as a benchmark for how elected officials ought to be perceived.”

Guines was no saint—in any way—and never pretended to be. He took risks and made mistakes, as was the case with the hiring of one superintendent he’d championed, only to soon realize he’d blundered: the superintendent was secretive and divisive, he was corroding board members’ relationships with each other and setting the district on what one board member described as a “corporate” course not made for Flagler schools, while verging on a school building bubble the district could not sustain. One of those schools (Matanzas High School) was shoddily built and had to be reconstructed in parts, while the district took the builder to court.

In those days, Evie Schellenberger, who served with Guines seven years on the school board—and had her run-ins with him and his acidic ways–says his wisdom stood out “as thinking of the future, not just what we needed right at the moment.”

The Catalyst

Guines helped the board avert disaster when, during the years of Bob Corley—the superintendent he’d championed, then opposed—he reminded the board that “you cannot build the future on growth, because you don’t know when that growth would stop,” Schellenberger remembered. “And of course it did. The fear was we’d build too many schools and we’d have too many empty buildings.” There are a few empty classrooms now, she says, but the overbuilding was limited, and by 2005 Corley, who’d pushed the board to create its own building department, had been pushed out, largely at Guines’s doing.

His decision to retire in 2007, just five months into his fourth consecutive term, was more than a shock. “If Guines’ absence has the feel of a death in the community,” a News-Journal editorial stated at the time, summing up his impact, “it’s largely because of what Guines has meant to the community in the last dozen years. Unquestionably, he’s been the School Board’s most involved member, personally mentoring students or creating mentoring programs from scratch, enabling educational programs for the less-than-privileged, like his Make-It-Take-It computer program (students build and own their own computers) or using his own money, from his board salary, to underwrite scholarships. There’ve been few community events involving students – sports, concerts, plays, fund-raisers – that he wouldn’t attend, usually with his wife, LaVerne. Often, it was his ‘Smokin’ Jim’ barbecuing enterprise that would get him to ballgames and festivals, though not for profit: Independently wealthy, Guines used his barbecuing to raise money for various causes. It was just such a fund-raiser (for a Catholic charity several months back), his last, that may have exhausted him beyond his limits. And those were just his activities away from the School Board. On the School Board, Guines was, notoriously, the shock to the system that the board has needed a few times in the last dozen years.” (In a letter to the editor, LaVerne Guines took exception to one phrase: “The editorial was factual,” she wrote, “with the only inaccuracy being that we are independently wealthy.’ The accuracy is that we live comfortably.”)

The Make-It-Take-It program has a special place in his memory. It was a way to get computers in the hands of poorer students, long before the district started developing its one-to-one computer initiative, which in the past few years placed a computer in each student’s hands. Guines likes to think of Make-It-Take-It as having been ahead of its time. “I am delighted that this school system has every classroom totally equipped for Apples,” he says, “and every kid has a chance to have a computer every day, and even at home, to take them home. So I’m proud of that.”

He was far from done even after retirement and despite illness. One of his newer undertakings: he was and remains a founding member of the FlaglerLive Board of Directors.

Audio: Jim Guines on the Mentor Program in a 2012 Interview

In 2012 he created the African-American mentor Program with then-Superintendent Bill Delbrugge and John Winston. It has survived and thrived in the hands of Winston–a man who exudes Guinesian energy and charisma. Guines speaks of it with pride, underscoring its principles: it’s not about giving young men (and, subsequently, young women) a big brother, but a moral center and high standards to rise to. It’s what’s enabled several of the program’s participants to go from the dean’s office (or worse) to the honor roll.

None of that begins to tell the story of Jim Guines. It may at this point sound like an obituary. But he’ll be the first to warn in a Twain vein: reports of his death are greatly exaggerated.

Recurrence of Violence

Guines was born in Chattanooga, Tenn., in 1932, one of two sons. It was a rough childhood. Poor, segregated, violent. When he was 6, he had tuberculosis. He spent nine months at the once-famous Pine Breeze sanatorium on the high grounds of North Chattanooga, sleeping in open-air porches in compliance with TB treatment at the time. (Pine Breeze closed as a TB sanatorium in 1968 and was converted to a mental health institution.)

When Guines was 8, his father was stabbed to death. His brother Bethel was murdered on April 14, 2005, in Chattanooga. He was 70 years old. He’d retired as a union leader from the Tennessee Valley Authority and volunteered his time five days a week, delivering breakfast to the poor and infirm in his Meals-on-Wheels truck. He kept a small firearm to protect himself, as the job required early morning deliveries through some of Chattanooga’s tougher neighborhoods. He was set upon by a couple who swiped his gun and forced him to an ATM for cash, then shot him in the head and dumped him in the woods. “For his good deed, trying to feed the poor, he was killed,” Guines says, still embittered by the memory.

Bethel Guines left behind a wife and four children. Januari Williams, a 26-year-old Chattanooga woman, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 20 years. She is eligible for parole in two years. “It does make a statement on black on black crime,” Guines said. “It’s real, it’s a real thing, it happened to my family.”

“Whippings Made Me Perfect”

One of his clearest memories from his childhood was a caning he got from his uncle, though that memory is more smiles and laughs than tears. He was somewhere between 8 and 10 and living with his grandmother. “We had a whole slimy pool that ended up at the end of a little run-down stream in the forest, we used to go back there swimming,” Guines remembers. “My grandmother would tell me please stay out of that swimming pool. It’s nasty, it’s slimy, and you’ll probably end up with a disease.”

Guines’s independence streak was part of his character from those earliest days. He defied his grandmother. He swam. Until his Uncle Doug caught him, forced him out of the pool—naked—and forbade him to put any clothes back on, ordering him instead to go on up ahead of him back to the house for his beating. Guines protested. He had to run through streets, even go in front of his girlfriend’s house. “I couldn’t hide my privates. When I tried he said no, don’t cover up, let it hang, I’m going to beat your butt when we get home.”

So Uncle Doug did. “He knocked me off the porch with one slug. I came back up and took my whipping,” he says. “Those two whippings I did get helped me be perfect. I remember those well to this day, although my uncle Doug is deceased, died of cancer.”

He remembers well: two whippings. The second was much worse, and came at the hands of his junior high school principal. “I would call that today serious corporal punishment,” Guines says. “The principal administered it to me out in the hall. I don’t know what I did, but I do remember the punishment. I could feel the lump on my butt for at least a week after that. That’s how hard he hit me.”

Guines would have his encounter with far worse violence. A grim rite of passage for so many young black men in America then as now, it would happen at the hands of white police. He was teaching at St. Augustine’s College by then, the historically black college in Raleigh, N.C. (now St. Augustine’s University). By then he’d served two years in the Army as a military policeman, taken his GI Bill and graduated college at Alabama A&M (now Alabama University), earned his Master’s and was either working on his doctorate or had earned it from the University of Tennessee.

He’d been one of just three black students admitted to graduate school at UT, with scholarships from the Southern Education Foundation and the Kellogg Foundation. The civil rights struggle was all around him. He’d steered clear of much of its more demonstrative aspects. But he was in the thick of it as an educator: he was called upon to teach integration and to integrate school districts in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, which Southern states resisted for many years.

A Cop’s Gun to His Jaw

One night at St. Augustine’s College a bunch of black college students were walking back to campus from a movie. Guines had been drinking. He saw two young white cops harassing the students. Guines intervened. “You guys shouldn’t be picking on these kids, these are college kids trying to get home and you’re creating a problem,” he told the cops. “Well, these two guys grabbed me up by my collar, put me in the back of the police car, drove me around back some place on the campus, pulled out their pistol, put it to my jaw, and said let me tell you something, ‘I’m going to blow your head off.’ I said, Let me tell you, if you do, you’re gonna make another Martin Luther King out of me. You’re gonna make another Martin Luther King out of me. And the guy said, ‘Look, let’s let this N-word go, he’s too damn smart.’ I’d been in college, I guess I was smart. But looking back on that experience and understanding now what’s happening to a lot of kids on the part of police, it scared the living crap out of me. It’s a wonder I didn’t get my head blown off. So I have been there.”

(Guines himself chose to say “N-word” in this case, though he’s not shied from the word before, and was livid a few years ago, and made his anger known, when the Flagler school board scrapped plans for “To Kill a Mockingbird” for fear of having actors speak the word on stage. His anger was part of the backlash that helped restore the play.)

That was the rougher side of Guines’s life. There was also the wilier side, the more playful side, the womanizing side, which still brings grins by the bounty to Guines’s expression. It really was at the root of his decision to go into education, elementary education especially. It’s simple. He was required to declare a major in college. “The prettiest girls I’d see in the room were elementary education majors,” he says. But few men went into the field. He did. “So I took classes with all girls. Some of them were pretty. It was a minor for some guys. That was my major.” He was presumably talking about his college major, but you never know with Guines.

“He’s a mess,” LaVerne says, sitting next to him.

He loved women. He got around them. “Yes I did,” Guines says with that broad smile. “I have one right now. I love my wife.”

Their courtship was classic Guines. He was married to his first wife when he met LaVerne, and he had a girlfriend (he was going through a divorce). He’d just moved to Washington, D.C., as assistant superintendent of D.C. District schools, a post he’d hold for almost two decades until his retirement to Palm Coast. (He’d also spent a four-year stint as an administrator in Richmond district schools, where he met one of his long-time friends, Doug Wilder, who’d become the first black governor of any state since Reconstruction.) In D.C., LaVerne was a supervisor of elementary education. Her office was on the same floor as Guines’s, though they hardly saw each other in the office, because LaVerne was always on assignment in schools.

The Taskmaster

Her first impressions of Guines were shaped by his tough, demanding managerial approach. “I wanted the supervisors to know that I’d met with the school board,” Guines said, “and as I told them, I hope you know that I’m moving to get you a set of balls, and I hope you know what to do with them. I wanted the supervisors to be hard on teachers, make them teach, make kids learn, so I wanted them to really get in there, and a teacher who wasn’t teaching, fire them.”

It’s the sort of approach that won him no friends among teacher unions, there or in Flagler County, where he had a running battle with the unions, but that earned him respect as a no-bullshit leader (a word he used frequently in his prime as a school board member, but privately, and less so now).

“We met at a friend’s apartment,” LaVerne says of their first encounter. “He had a friend visiting him that weekend, a girlfriend, but meantime he wanted me to give him my phone number, which I did. He didn’t call me for a week, so then I checked on him.” They lived a block apart. “I left a note at the desk at his apartment building.” He claimed to have lost the number. She gave it to him again. Then she was the one who invited him to dinner. It wasn’t long after that the couple traveled to New Jersey to meet LaVerne’s parents, where Guines asked her father for her hand in marriage. They married in 1972.

“We’ve been married happily ever since,” he says. “No more girlfriends.”

Palm Coast

When LaVerne’s mother and stepfather lived in Ocala, the Guineses had a condo next to them. They were introduced to a Realtor who introduced them to Palm Coast, where they figured getting involved in a young community would be easier than in a settled one like Ocala. So they decided to move to Palm Coast when Guines retired in 1988. The couple got involved in the African American Cultural Heritage Organization, an organization separate from the African-American Cultural Society, and still around. On one occasion Guines delivered a speech on the theme of “Keepers of the Culture.” It caught the attention of then-ITT CEO James Gardner (father of the current property appraiser), who helped Guines forge his way into the Rotary and a broader role in the community.

He was first elected to the Flagler County School Board in 1996, beating Richard Wieser with 55 percent of the vote. He never lost an election, and his last, in 2006, when he beat Richard Marier, garnered him 69 percent of the vote, by far more than any other local elected official.

There’s a bit of confusion about his party registration—even for Guines these days. He is referred to as a Republican, and he was, in fact, a Republican in his years on the board. But that was at the suggestion of Theda Wilson, who had preceded him as the first black candidate to win an election to the Flagler school board. Guines had been a life-long Democrat, and he still is a liberal in most ways. But Wilson advised him to switch, if he was to be successful locally. Even then, she’d sensed the shift away from Democrat locally. Guines followed the suggestion, which proved politically useful. But he’s since switched to Independent, like LaVerne—and was an Independent when Holley, who was preparing a run for the county commission, approached him “as another African-American Republican,” in Holley’s words, thinking one Republican could advise another on local elections.

Most issues on the school board had little to do with ideology and a lot to do with socio-economic trends: growth, poverty, the divide between high and low-performing students, access to technology.

All of that has faded now. Guines hasn’t. Not just yet. “My wife always tells me you don’t need no credit for this or for that, God knows what you did, and as a Christian I accept that.” But he’s not looking forward to Sunday’s tribute any less. His only regret: not to be able to fire up the barbecue pit and serve as Smokin’ Jim.

–Pierre Tristam

![]()

The profile was originally published on Nov. 20, 2015, under the headline, “The Live Profile: Jim Guines, Smokin’ Shock to the System and Now 83, Will Be Celebrated Sunday,” ahead of the “Dr. Jim Guines Appreciation Event.” The comments that appeared at the time have been preserved.

Kendall says

Thank you for such a wonderful article about one of our own local “legends.” So glad to hear he’s doing well and is being honored this weekend! Flagler County is so luck to have Dr. and Mrs. Guines!

Geezer says

Jim Guines sure seems like a swell guy.

How nice to see later in fife that many appreciate him.

This is what a meaningful life looks like.

Well done sir.

Mr. Guines – this Bud’s for you!

Aves says

Thanks for doing this amazing profile on Smokin’ Jim! I’m one of the students impacted by his scholarship fund. It helped me graduate college. He’s a great man and a great educator and I didn’t know some of his history. Now I’m sorry I live out the state and can’t go to the fundraiser.

Frances Royals says

As a teacher in Flagler County for many years, I got to know Mr. Guines and appreciated his support through the years. He mentored some of my students and was always supportive of me as a teacher. He really understood some of the needs that our students have that are often not addressed by our educational system. What a great celebration for Jim, an intelligent man with a great sense of humor and a real desire to help the young people of our county. I wish him the best.

Veronica Maggs Thornton says

I ran the Make It-Take It program of which Jim seems so proud. He should be! It changed the lives of many, not only here but overseas as well. There are children in Africa and The Philippines who have access to technology thanks to his vision with Make It-Take It. There is so much more I cannot start to tell. They don’t make them like him any more. A man who changed thousands of lives, including mine

Anonymous says

Happy Birthday Jim

David B says

Always loved Smokin’ Jim’s BBQ chicken dinners at the FPC football games.

Cheryl Massaro says

Dr. Guines was an amazing man and even better mentor. Years ago, prior to my employment with Flagler schools, Dr. Guines took time to meet with me and guide me through the hiring process. Jim Guines alone supported my goal to manage the then new Flagler County Youth Center. My accomplishments would not of happened without his guidance. Flagler County, may have lost his physical presence, but I know his spiritual support and influence lives on!

Jack N says

He was a remarkable person

Wendy Watson says

Jim was my patient for 7 years. He meant everything to me. He made my life so much more the happier and better in so many ways. He wasn’t just my patient, he was my family. My heart is broken 💔 and he will be missed more than you know. I sit in his house now and the silence is deafening. He’s not here picking on me or yelling at me or just being my JimBob. I was there with him all week as well as LaVerne and Jim’s daughter Kimberly and her husband Ervin. We shared stories while we laughed and cried. Life will not be the same without him for sure. But we will hold on and be strong and I will keep being with LaVerne. I promise to keep her strong and keep her going. She’s one of the strongest women I know. We will be ok….. Just for you our sweet Jim.

Stacey Smith says

As a former long time employee, I can say he was one of the best people Flagler Schools ever had. He stood firm on his beliefs and didn’t care what others thought about him. Blessings on the other side.

Kimberley Guines Blowe says

My father was one of the strongest and bravest men I’ve ever known. He seemed fearless. To many, he was a mentor. To me, he was a loving father. I was always his baby girl—no matter how old I got.

I was truly blessed to have such a remarkable human being in my life. One of my favorite memories is riding in the car with him, music playing, just the two of us talking about everything and nothing. He’d look over at me and say, “Daddy loves you.” I never doubted that he did.

He made me feel seen, supported, and loved—throughout my life. His presence was a constant source of strength in my life.

Words can’t capture the depth of my grief. Losing him has left a hole in my heart that can never be filled.

I will miss him forever.

I want to thank LaVerne Guines (Mama L), and Wendy (his Care Giver), who took such good care of him during his health struggles. Their love, patience, and devotion meant so much to him—and to all of us who loved him.

Love you Daddy