“People crave attention,” Jack Lawson, one of three lawyers and four characters in David Mamet’s “Race” says toward the end of the play. “They crave money, ‘they’ are envious and sinful, just like you and me. A case, will grow, and develop, and ‘declare’ itself as it develops. Just like any illness.”

“Race,” which opens Friday at Palm Coast’s City Repertory Theatre and should be a highlight of CRT’s third season, is just such a case. It declares itself with the alleged rape by a very rich, famous, married, early-middle-age, white man of a black woman half his age. He seeks legal representation from a firm of three lawyers, two of them black, one white. Jack is the white one, the gravitational center of the play and its most accomplished character. It’s on the fault lines of his failed liberal assumptions on race that the case, and Jack’s relationship with his fellow-lawyers, will hinge.

Case and story develop and grow like an illness, infecting you–the audience–along the way, with sharp humor and sharper send-ups of stereotypes on race, sex, wealth, the media. But at the heart of it all is that familiar illness, the most familiar in all American history: racism. And Mamet takes it on with reactionary zeal worthy of Clarence Thomas and humor worthy of Antonin Scalia. (“It’s appalling what the government has done to the great African-American community in the last 50 years,” Mamet said in a recent interview in The Times.)

“When I first read ‘Race’ last spring,” John Sbordone, who’s directing the play, said, reading from his directors’ notes on ‘Race,’ “I thought, this is what CRT was founded to do. The play roared from the pages. The message screamed to be heard. As David Mamet writes, ‘race is the most incendiary topic in our history, and the moment it comes out you cannot close the lid on that box.’ That we hope is the outcome of this show. We want to open the lid on that box, and raise the discussion of this multi-dimensional issue to new levels. But that’s not all. We believe that Mr. Mamet’s writing deserves to be experienced in Palm Coast. This extraordinary American artist gives voice to the conscience of our country and must be given a platform.”

In Palm Coast especially, Sbordone says, since no Mamet play has been staged here before, and Flagler County has had its own disturbing history with race. “We were one of the last counties to desegregate,” Sbordone says. “We go back not too long ago to the issue of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ at the auditorium. It seems to be coming and popping up all the time.” The school district banned a student staging of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” three years ago, fearing that it would trigger racial unrest, then reinstituted the play after an outcry.

There is barely a faint thematic connection between Harper Lee and David Mamet. But it’s there. Mamet is essentially retreading the Mockingbird story in reverse, with what could pass as a nod to Lee: “Fifty years ago,” Henry Brown, one of the black lawyers in ‘Race,’ tells the accused rapist, “You’re white? Same case. Same facts. You’re innocent.”

But it’s not 50 years ago. And there’s nothing like a noble Atticus Finch in this “Race.”

A David Mamet play does not propose to let us spend an hour and a half in the presence of pleasant, happy or bearable characters. Mamet’s men—his women are not nearly as well realized or believable—are grasping, desperate, mean, angry, wasted. They are workplace Neros. They are furnaces of conflicts. Work is their narcotic. You never get the sense that they work to enjoy life. They work to escape it, and escape themselves. And they’re captivating. You just can’t look away. Mamet’s artistry is in creating these human train wrecks and inviting you to watch from a front-row seat. Plenty to see here. Don’t move along. Don’t worry: you won’t.

In “Glengarry Glen Ross,” Mamet’s most celebrated and accessible play, the escape—the job—becomes the trap, the torture chamber that forces the men of a condemned real estate office to face themselves and each other in a obscene game of “Survivor” (a generation before that pastiche became a TV hit: “Glengarry” won the Pulitzer in 1984). The artillery of obscenities alone is worth the price of admission.

“Race” keeps the obscenities to a minimum for a Mamet play, though your ears will hear a few lines you’re not likely to have heard in a very long time. The subject matter is obscenity enough. But as in “Glengarry,” the workplace—a lawyers’ office—is the subject of an intrusion that forces three lawyers to put their own assumptions, their stereotypes and bigotries, on trial. They don’t know they’re doing it. That’s the master stroke of the play: here are three lawyers trying to come up with a strategy for a trial who are putting themselves on trial for the audience, as each cross-examines the other’s vulnerabilities. Line after line reveals degrees of guilt that Mamet, with more pleasure for himself than the audience, spreads around. Mamet’s judging hand is at times more heavy-handed than it needs to be, because American artists from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Mark Twain to Spike Lee to Mamet are incapable of dealing with race at any length without at some point going pulpit on their audiences. But they’re not to blame. America’s original sin is.

Sbordone loves plays that unnerve his audience. “Yes, I expect everybody to be bothered,” he says, the words rolling off his tongue with the same relish as Jack Nicholson’s “Here’s Johnny” n “The Shining.”

“If not,” Sbordone specifies, “then we will have failed.” And bothered “regardless of color, regardless of gender. I think everyone will find something to ponder, think about in their own lives, their own preconceptions.”

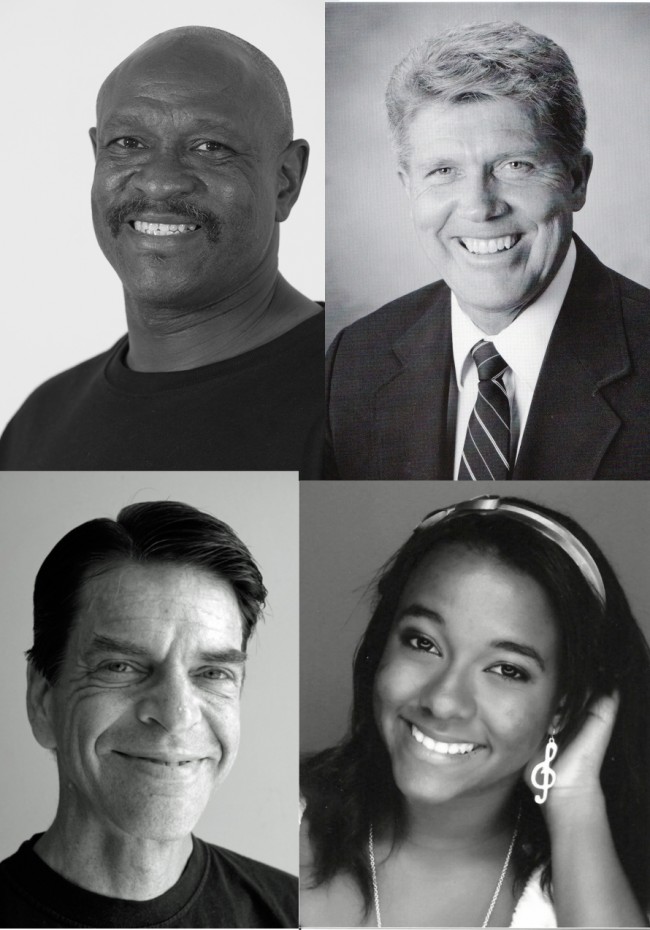

“Race” does that in spades, though Sbordone has had to work for it. Half his cast changed during rehearsals (Renny Roker was to play Henry, the role now played by Tony Felton, a writer-actor-bus-driver). Jack is played by John Pope (Henry in CRT’s “Lion in Winter”). Charles, the alleged rapist, is played by Jonathan Haglund, the year’s most recurring actor on CRT’s stage. And Philippa Rose, a graduate of Matanzas High School who worked in plays with Sbordone there and is just back from Florida A&M, is the third lawyer (“Susan”), and the wrench in the story. Susan’s thesis in college? “Structural Survivals of Racism in Supposedly Bias-free Transactions.” The fifth character is not a person. It’s sequins. They’re all over the place, figuratively and literally.

“Race” is above all a thrilling dramatic ride with successive twists and ambushes and surprises, a detective story as the play’s continuo and a good many hilarious one-liners. “There are no ‘facts of the case,’ Jack tells Charles at one point. “There are two fictions. Which the opposing teams each seek to impress upon the jury.” And the audience.

By the end of the play you’ll feel like you’ve ridden a rollercoaster. You’ll also have a multi-track debate going on in your head, or with your date, or with your past, or with your guilts, or with your prejudices.

That’s just the way Sbordone wants it.

![]()

“Race,” by David Mamet, directed by John Sbordone, with Anthony Felton, John Pope, Jonathan Haglund and Phillipa Rose, at the City Repertory Theatre, Hollingsworth Gallery, at City Market Place in Palm Coast. Feb. 17, 18, 24, 25 at 7:30 p.m., and Feb. 16 and 23 at 2 p.m. CRT is located at 160 Cypress Point Parkway, Suite B207. TICKETS: $20 for adult s, $15 for students. Get your tickets easily here, or call the box office at 386/585.9415

Perry Mitrano says

What a moving play. This group of actors live the part. If you have never seen a play at CRT you must give them a try. I have never been disappointed. Thank you John and Diane for this theater.