They’re both arresting paintings. In Marc Chagall’s “Music,” from 1920, a dark-green-faced, bearded, Jewish violinist plays his instrument with a grin that sings pure joy as he floats over houses in clothes that could just as well be parts of his instrument, or scrolls of music. He’s dancing without having to make a move. A boy floats higher above him, his arms outstretched as if to say: my playground. Amuse me. It’s a mood of deep greens and dark browns against a pale background, the violin alone standing out in bright orange, a powerful color of happiness.

No wonder Fred Samuelson’s interpretation of the same painting decided to focus on color and movement in his reinterpretation of the painting: his violinist is given over to shades of violet, with one small orange exception, there are no background stories, only a large window behind the musician, and the musician himself, or herself for that matter, literally multiplying and shimmering to the vibrations of the instrument. Elements of the cubist original are preserved, but it’s an entirely original painting, not an imitation. Chagall here is just a theme. The painting is the variation.

Inspired By Chagall:

- Opening at Hollingsworth Gallery Saturday, March 12, with a free reception from 6-10 p.m. The gallery is located at City Market Place, 160 Cypress Point Parkway, Palm Coast. Call 871-9546 for details.

So it is with the entirety of the new show at Hollingsworth Gallery, opening Saturday evening (March 12): “Inspired by Chagall.” The show is actually presented by Beaus Arts of Volusia, and particularly Beau Wild, the Daytona Beach artist who just had a show of her own at GOLA (Flagler Beach’s Gallery of Local Art), who invited artists to create works inspired by specific works by Chagall, the Russian-French artist whose popularity in the 20th century was matched by few others (he died in 1985, at age 97). The works are varied and variously challenging—one or two of them nearly exact copies of an original Chagall, most of them variations, like Samuelson’s violinist, on particular Chagall themes.

For those who love Chagall, it’s a way to see how the old artist’s enchantment adapts to younger generations. For those who don’t know him, it’s an engaging way to come and learn about one of the greats. Wild asked every artist to include a brief explanation of his or her work, along with the original Chagall that inspired it. It avoids a good deal of head-scratching or frustration and makes the show that much more accessible—and unpretentious. Even young children can delight in it and understand it on their own terms, the way Chagall’s work is meant to be seen. He was not one for theory or art for complexity’s sake. He was about folklore, childhood memories, Jewish life, dreams and wonders, a sort of Yiddish Miro.

Click On:

- Humane Safari: Alms for the Paw Opening At the Flagler County Art League March 12

- In Your Face: Palms and Heads Color Hollingsworth Gallery Opening

- What’s All the Fuss About? A Gallery of Provocative Art From 3 Local Shows

- On Point: Color Splash from Hollingsworth To the Art League

- Encore: Flagler County Artist of the Year Edson Beckett at Hollingsworth Gallery

- Portrait of a Transcending Mind: J.J. Graham’s Hollingsworth Gallery Genesis

“The way I look at it,” Hollingsworth Gallery owner JJ Graham says, “is kind of like when we go to a concert and you see a band that has their own style, like Pearl Jam, and all of a sudden they do this great Led Zeppelin cover but they do it in their own way. A lot of these artists I know personally, they have their own highly developed style and direction, so that’s the way that I see this. They’re paying homage and doing interpretations of his work in their own way. It’s really educational because you get to see a tradition, you get to see reflections of a great artist who’s stood the test of time so far.”

Don’t expect to see anyone competing with Chagall in this show. The artists are likely too smart to try. No one can really compete with Chagall whole, not just because there’s too much of him, his creativity and abandon busting every seem in sight, but because no one has his experience: his Jewish origins in a Russian shtetl, the source of his greatest works, has been entirely erased by Russian pogroms, the Nazi holocaust and Stalin’s collectivization. His paintings are like the writer and Nobel Laureate Isaac Singer’s stories of the same kind of life in Poland. They’re the most vivid testament to that life. On top of it all comes Chagall’s ability to make music out of color and color out of poetry, as if he were painting with his soul rather than a brush. “You see that element of play in his work. A bird flies out of one painting into another, then the violinist takes on the persona of the bird and floats over the city,” Graham says.

Gravity barely exists in Chagall. Whether it’s people, objects, color or perspective, physics is nonexistent in Chagall. Imagination is all. In “Birthday,” a painting inspired by his fiancée Bella Rosenfeld, a sense of transporting joy fills the whole scene as the man, seemingly armless and suspended in air, curves his neck impossibly toward his beloved to give her a kiss while she herself hovers above ground, a bouquet of flowers in her hand. The bed, the carpets, the scene outside the window all seem to float so vividly that the flattened perspective of the painting is more multi-dimensional than if it were in 3-D. Chagall was recreating his moment with Bella, who described him actually painting “Birthday” in 1915: “You flung yourself upon the canvas so that it quaked under your hand; you snatched the brushes and squeezed out the paint—red, blue, white, transporting me in a stream of color. United we float over the decorated room, come to the window and want to fly out. The brightly hung walls whirl around us. We fly out over fields full of flowers, over shuttered houses, roofs yards, churches.”

Chagall painted with the kind of loving violence that Graham does, which helps explain the affinity Graham has for the master. “He’s a shining example of the kind of artist I’m looking for in this gallery,” Graham says. “He’s not afraid to tell his own story, use his own imagery, apply his own poetic sense to paint. His work wasn’t strategically designed to go over somebody’s beach house sofa.”

For Chagall, objects become the extension of his characters’ imagination, and color is their magic carpet, taking that imagination beyond the imaginable. Of course artists want to ride that carpet. He makes it so desirable, if not at all easy. So rather than compete with him, the artists of Beau Wild’s collection have wisely chosen to adapt specific strands of Chagall. There’s plenty of him to go around.

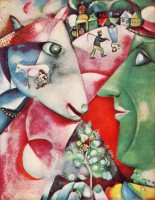

When you walk into the Hollingsworth Gallery, be sure to have a look at how “I and the Village” influenced two very different artists.

“I and the Village” is one of his most recognizable paintings, and one of his richest. He painted it in 1911, when Chagall had just arrived in Paris and his childhood memories had all the vividness of the present and none of the calcifying nostalgia of older age. When you look at the cubist painting at first you see a clownishly green but human profile dominating the right of the frame, looking at a the rounder head of a white and blue horse staring back. There is a strange filament extending from the eye on one figure to the eye on the next. Maybe the green face is Chagall’s, and the thread is the mystery of memory that enables him to recreate what we are about to see, when we look just a bit longer: scenes from the story of a young lifetime. A girl milking a goat embedded in the face of the horse, a farmer walking with his sickle toward a woman walking upside down, with houses alternately upright and upside down behind them. It’s the topsy-turvy world of a young boy’s fun. What young boy hasn’t rearranged the world to his whimsies, toppled reality to remake it in his fancy’s image?

To Naomi Lee Berlin, who titled her interpretation of Chagall’s piece “My Village,” hers is “New York City and the symbols I used to celebrate my love for the city. The stylized cow jumping over a full moon represents the richness of life in the lightly lit city, the dancing rabbi and the horse the freedom enjoyed by the diverse culture of the city.” The relationship between Chagall’s and Berlin’s villages is distant, in time, perspective and even richness. Berlin alludes to symbols rather than tells stories that become symbols, in Chagall’s hands. But even if Berlin’s image had none of the help of an explanatory note or was entirely disconnected from the nearby Chagall, it would still convey, with that flying, smiling, barefoot girl in the middle of the frame, that child-like delight in rearranging the world’s furniture out of its conventions.

Kathy O’Meara takes the same painting and goes in a radically different direction. She’s adapted her village to America, too, but by turning to abstraction, mixing media (there’s a sudden, square burst of cardboard that could represent more rundown homes, and filling in much of the story with ample doodles that suggest rather than tell any definite story. The work evokes both petroglyphs and a palimpsest—as if the artist is conveying the erasure of memory, rather than its childlike vividness. The longing that’s found in later Chagall comes to mind, in much different form: Chagall never lost his memory. He merely went too kitschy.

That’s just two examples. It’s a lot richer than that in person, from a complete and perhaps puzzlingly sober reinterpretation of “Birthday” to a free-standing mixed-media installation by Louise Lieber, who reinvents “Paris Through My window,” down to “Pink Trailer Days,” a terrific Chagallian work by M.S. Reynolds that Chagall himself might have painted had his shtetl been what American shtetls are, with Southern Baptist overlays—cozy ragtag collections of wears and tears, the odd cow and ancient washing machine included, along with that signature Chagallian affection for lovers’ warmth. Reynolds in this trailer scene does what Chagall would have never done in his early days, but would certainly appreciate in this interpretation: the girl in the picture is pregnant. Happily so it seems rather than by accident: girls who get pregnant by accident don’t have pretty fresh flowers in a vase next to their bed. The story-telling in this painting, which—when I saw it—appeared near the end of the show if you take it in in a counter-clockwise way, closes the circle perfectly on Chagall as Russian memoirist to Floridian transplant.

Leave a Reply