The Ten Books of Christmas: Between Christmas and New Year’s FlaglerLive customarily reduces production. It helps us, and no doubt you, exhausted reader, to take a break from outrage and lurid politics. This year I’m doing something a little different. Instead of only running the usual end-of year sum-ups and fillers, I’m launching the Byblos column and offering the Ten Books of Christmas: every day I’m publishing an original piece of mine on one of the books of the year I found most notable—books old and new, fiction and nonfiction, whether inspired by covid, confinement, covfefe or just the libidinous, inebriating pleasure of reading. No doubt only six or seven readers out there are interested in this sort of thing. That's OK. They’re ignored the rest of the year, so this is for them. I hope they find these, ahem, brief reflections (rather than reviews) at least a little provocative. The days' installments are listed below. --Pierre Tristam |

![]()

At his best he could write more clearly than Thoreau, had none of the dullness of John Muir, could be more forceful than Rachel Carson, and would always have more literary flair than Bill MicKibben. But in the mid-1960s Edward Abbey was despairing about his lack of success.

He’d had three novels published, without much noise. Kirk Douglas had turned one of them, The Brave Cowboy, into a movie, calling it Lonely Are the Brave. Abbey was barely paid. He’d been a $1.95-an-hour seasonal park ranger at national monuments in the west and in the Everglades to live and pay for booze–his ultimate downfall–wives and mistresses (“Whenever I discover a natural scene that pleases me, that I find beautiful, my first thought is: What a place to bring a girl!”)

He’d had three novels published, without much noise. Kirk Douglas had turned one of them, The Brave Cowboy, into a movie, calling it Lonely Are the Brave. Abbey was barely paid. He’d been a $1.95-an-hour seasonal park ranger at national monuments in the west and in the Everglades to live and pay for booze–his ultimate downfall–wives and mistresses (“Whenever I discover a natural scene that pleases me, that I find beautiful, my first thought is: What a place to bring a girl!”)

“He wanted the same thing all writers want–fame, money, beautiful girls,” he wrote in his Thoreau-length journals, using the third person. He thought highly of himself. He couldn’t match impact with ambition.

“Just write about your camping trips,” his agent Don Congdon told him, according to James Cahalan’s 2001 biography of Abbey. “Can I really do that? Will that make a book?” So he did, transforming journal entries and notes from his seasonal work, especially two years at Arches National Monument in Utah, into American impressionism in prose.

What a book it made. Desert Solitaire, published in January 1968 and worthy of any top-100 list of the best books of the last hundred years, is a meditation, a polemic, a manifesto, a provocation, a valentine and an elegy to the red desert and to American wilderness. It is also as much memoir about a vanished wilderness as Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short stories are about Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto. Almost everything Abbey describes, including the serenity of Arches park, is gone but the grounds and the sky. In vast places, like where Lake Powell invaded after Glen Canyon Dam was built in 1966, even the ground is gone.

One of the 18 chapters of Desert Solitaire is a last voyage through Glen Canyon country before it started filling with water in March 1963. Abbey would have liked to blow up the dam, which he considered a crime against nature. “[T]he proper answer to this typical act of politico-industrial vandalism,” he wrote in a June 1969 review of a Wallace Stegner book, “is not the acceptance of what is now called Lake Powell but rather the demolition of Glen Canyon Dam,” an idea Abbey would develop as environmental terrorism chic, and that would take shape in his second-most famous book, The Monkey Wrench Gang. Four years after the founding of Greenpeace, the 1975 novel sought to legitimize ecological sabotage in defense of the environment. That was before 9/11 and school-massacre laws sabotaged the First Amendment and turned thoughts and words into acts of terrorism.

It is in that chapter that he defines wilderness (“The word itself is music”) as an Eden far west of the mythical one. “The word,” he writes, “suggests the past and the unknown, the womb of earth from which we all emerged. It means something lost and something still present, something remote and at the same time intimate, something buried in our blood and nerves, something beyond us and without limit. […] But the love of wilderness is more than a hunger for what is always beyond reach; it is also an expression of loyalty to the earth, the earth which bore us and sustains us, the only home we shall ever know, the only paradise we ever need—if only we had the eyes to see. Original sin, the true original sin, is the blind destruction for the sake of greed of this natural paradise which lies all around us—if only we were worthy of it.”

The environmental historian William Cronon might not be kind to that perspective. “Go back 250 years in American and European history,” he wrote in “The Trouble with Wilderness,” a 1995 essay in which he paid tribute to Stegner but not Abbey, “and you do not find nearly so many people wandering around remote corners of the planet looking for what today we would call ‘the wilderness experience.’ As late as the eighteenth century, the most common usage of the word ‘wilderness’ in the English language referred to landscapes that generally carried adjectives far different from the ones they attract today. To be a wilderness then was to be ‘deserted,’ ‘savage,’ ‘desolate,’ ‘barren’—in short, a ‘waste,’ the word’s nearest synonym. Its connotations were anything but positive, and the emotion one was most likely to feel in its presence was ‘bewilderment’ or terror.”

That’s what Abbey wishes could be recovered. He doesn’t mind a bit of terror, especially if it keeps people away. He longs for the barren, the savage, the desolate. That’s what’s been destroyed by the commodification of wilderness into monuments, preserves, parks. He reviles the enclosing and scarring of nature into delineated trails, scenic spots and picture spots. I could see him setting off plastic charges at every visitor center and gift shop. And don’t get him started on roads in the wilderness, even in national parks.

Abbey hated cars. He hated drivers “born on wheels and suckled on gasoline, who expect and demand paved highways to lead them in comfort, ease and safety into every nook and corner of the national parks.” He called cars “sand-pitted dust-choked iron dinosaurs.” It wasn’t a new idea: Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, a liberal who refused to buy a car, opposed a national road system and wouldn’t have minded if Detroit were “Blown off the face of the earth.”

Abbey wanted to blow cars and paved roads only off national parks. “You can’t see anything from a car; you’ve got to get out of the goddammed contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus,” he yelled. Motorized tourists were “being robbed and robbing themselves. So long as they are unwilling to crawl out of their cars they will not discover the treasures of the national parks and will never escape the stress and turmoil of those urban-suburban complexes which they had hoped, presumably, to leave behind for a while.”

Desert Solitaire’s least poetic, most polemical chapter (he titled it a “Polemic”) is also its most influential, at least as far as park management is concerned. The National Parks system adopted Abbey’s recommendations in a few places. In “Industrial Tourism and the National Parks,” he made a simple call: “No more new roads in national parks.” And he went further: “No more cars in national parks. Let the people walk.” He’s the reason Zion National Park banned cars on some of its roads in 2000. Yosemite restricts vehicle traffic, if not that much, as does Yellowstone.

He doesn’t mind horses, bicycles, mules, and doesn’t mind shuttle buses. Otherwise, no motorized contraptions, motorcycles included. “We have agreed not to drive our automobiles into cathedrals, concert halls, art museums, legislative assemblies, private bedrooms and the other sanctums of our culture; we should treat our national parks with the same deference, for they, too, are holy places. An increasingly pagan and hedonistic people (thank God!), we are learning finally that the forests and mountains and desert canyons are holier than our churches. Therefore let us behave accordingly.”

I’m writing this on one screen while on another The National Park Service’s visitation numbers scroll on: 327 million visits in 2019, and that wasn’t even a record. In October the Deseret News reported that the gate to Arches National Park had to be closed over 100 times for overcrowding this year. It was on pace to break its 2019 record of 1.7 million visitors. In 1956, the first year Abbey was a ranger there, Arches, still a national monument, drew just 28,500 visitors.

Desert Solitaire really is a eulogy.

I read the book every few years, never tiring of it. I read it again during the Pandemic. It was a way to oppose confinement with the experience, half imagined, half with Abbey as guide, to go back to Arches and other national parks I’ve loved visiting (not without my car, but also in a few shuttles, and a lot on foot). The book’s opening chapters include some of the grandest naturalist prose in American literature, the red wasteland of Arches park become an eden and every surface of sand, stone or a snake’s skin transformed into immeasurable beauty. Abbey rejects progress as either purpose or value. He rejects even more–and this is a lesson eons ago unlearned–the uses of nature as filling a purpose other than its own, especially a human purpose. Even when we say such things as “parks are there for our enjoyment,” we have unlearned to see nature as it must be seen–as its own end, not as a means to our enjoyment. The enjoyment is incidental, a privilege bestowed rather than a right owed.

This is how Abbey approaches his environment in the first few chapters, and this is where, stylistically, he achieves something most naturalists do not. He abandons anthropomorphic similes and metaphors: “Like a god, like an ogre? The personification of the natural is exactly the tendency I wish to suppress in myself, to eliminate for good. I am here not only to evade for a while the clamor and filth and confusion of the cultural apparatus but also to confront, immediately and directly if it’s possible, the bare bones of existence, the elemental and fundamental, the bedrock which sustains us. I want to be able to look at and into a juniper tree, a piece of quartz, a vulture, a spider, and see it as it is in itself, devoid of all humanly ascribed qualities, anti-Kantian, even the categories of scientific description. To meet God or Medusa face to face, even if it means risking everything human in myself. I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a nonhuman world and yet somehow survives still intact, individual, separate. Paradox and bedrock.”

He then takes us into that bedrock. That’s Desert Solitaire, “the center of the world, God’s navel, Abbey’s country, the red wasteland.”

That’s the great Abbey. There’s also the crabby Abbey, the reactionary Abbey. That Abbey makes only a few appearances in Desert Solitaire and many appearances in his other works, his essays especially. There was a suggestion of racism in Abbey’s polemics, which his ex-wives and his biographer went to some lengths to discredit, though he betrayed it even in his lyricism. “Very quietly and selfishly, all by my lonesome, I cook and drink and eat my supper, smoke a cigar for dessert, finish the wine,” he writes toward the end of Desert Solitaire. “The stars look kindly down. Drunk as a Navajo I pull off my boots and crawl into the snug warm down-filled womblike mummy bag.” Drunk as a Navajo? Mild, compared to what came next.

He would have loved Trump’s war on Mexican immigration. In 1983 he wrote “The Closing Door Policy,” an essay later revised as “Immigration and Liberal Taboos.” Not yet Cotton-swabbed, The New York Times turned it down after soliciting it. It’s the blueprint of a Trump executive order. Abbey ridicules the transformation of illegal alien into “undocumented worker,” sneers at the pregnant Mexican “who appears, in the final stages of labor, at the doors of the emergency ward of an El Paso or San Diego hospital, demanding care for herself and the child she’s about to deliver” as an “automatic American citizen” no less, and calls for the closing and militarization of the border. “We’ve got an army somewhere on this planet, let’s bring our soldiers home and station them where they can be of some actual and immediate benefit to the taxpayers who support them.” He thought “a force of 20,000, or ten men per mile, properly armed and equipped, would have no difficulty—short of a military attack—in keeping out unwelcome intruders.” (some 3,000 troops are deployed currently).

He was not big on feminism, either, or the conventional gloss of National Geographic’s take on world and nature. Writing for the magazine was in his experience “like trying to jerk off while wearing ski mitts.” He despised the East Coast literati, calling John Updike “the Englebert Humperdinck of contemporary American Lit,” Saul Bellow a “friend of power, hierarchy, techno-industrialism,” Tom Wolfe “a sycophant to the wealthy and powerful.”

In a review of Wallace Stegner, his competition, whom he found mired in “an excess of moderation, an extremity of forbearance,” he managed to take a swipe at Philip Roth and James Baldwin in a paragraph that suggests he would have appreciated Trump’s combative schmaltziness for a white-nationalist America disappearing as surely as the ground beneath Lake Powell: “How can a writer burdened with such a load, ‘still half believing in the American dream,’ compete with angry transvestite poets of the Negro persuasion or with sex-tortured Semites from the biog cities making a lifetime literary project out of their Jewishness? It ain’t fair.” Lines like that rankle today (but then so do innumerable lines in Roth and Updike that wear their misogyny on their fonts.)

None of that explains how Abbey could pull off a book like Desert Solitaire. His agent seems to have been a catalyst with his campfire idea. So might have a pamphlet circulating among rangers at the time, though this is pure speculation on my part.

In 1955 the National Park Service issued the 84-page booklet called “Campfire Programs: Training Bulletin for Field Employees of the National Park Service United States Department of the Interior.” Even the typewritten appearance betrayed the title’s bureaucratic slog. But the booklet starts below a quote from Edwin L. Sabin, the forgotten writer of adventure stories of the West (“But see—a spark, a flame, and now The Wilderness is home”). It goes on to quote Seneca, Tennyson, Shakespeare and Lewis Caroll. Abbey’s kind of pamphlet.

The writer is H. Raymond Gregg, a National Park Service naturalist who had a few journal articles to his credit and six years of “Nature Sketches” that aired from Rocky Mountain National Park on NBC’s radio network. His training pamphlet for “campfire leaders” was a manual for rangers participating in a national parks tradition going back to the 1930s. The tradition is still around, but in competition with too much of that theme-park entertainment that’s degraded the park experience over the years.

Gregg wrote at a time when the campfire talk was its own reason to visit parks, when visitors didn’t prevent themselves from immersion with their portable satellite dish and smart phone, when they weren’t segregated by AirpPods, steel boxes on wheels and asphalt that delineates the distance they’re willing to travel, when the campfire talk was “the only public function in the park during the evening hours.” He wrote when Abbey worked the parks.

“A ‘box office’ approach is not needed to attract and reach the audience,” Gregg wrote his trainees. “You need never lower your program standards on the justification that ‘the people like it,’ or ‘this is what the people want.’” A fire is as primitive as it gets. Gregg is trying to teach his future “leaders” how to seduce their audiences back to the primitive. Imagine reading that in any kind of pamphlet about any experience today, when give the people what they want is often the only standard.

If we can’t be sure that Abbey read this pamphlet, he probably would have had to. It was issued a year before he was a park ranger at Arches National Monument. He spent two seasons there, 1956 and 1957, from April to September.

He didn’t intend them that way, he doesn’t present them that way, but the 18 chapters of Desert Solitaire are 18 campfire talks, each distinct from the other, each in a different voice and to a different end, the whole forming a portrait as much of Abbey as of his Southwest desert. A couple of the chapters, like “The Moon-Eyed Horse” and “The Dead Man at Grandview Point,” are fictional stories passed off as nonfiction. The voice is so distinctive, the themes and the lyricism at times so epic, the reader can hear Abbey’s voice honing his prose from one campfire to the next like the comic honing his stand-up act from one small town stage to the next, until he was ready for hardback covers.

He had no idea he was writing a classic. I’m betting it’s a matter of time before the Library of America rediscovers him and issues his greatest works, including a selection of his essays: there are at least a thousand good Abbey pages to preserve for posterity. It’s time.

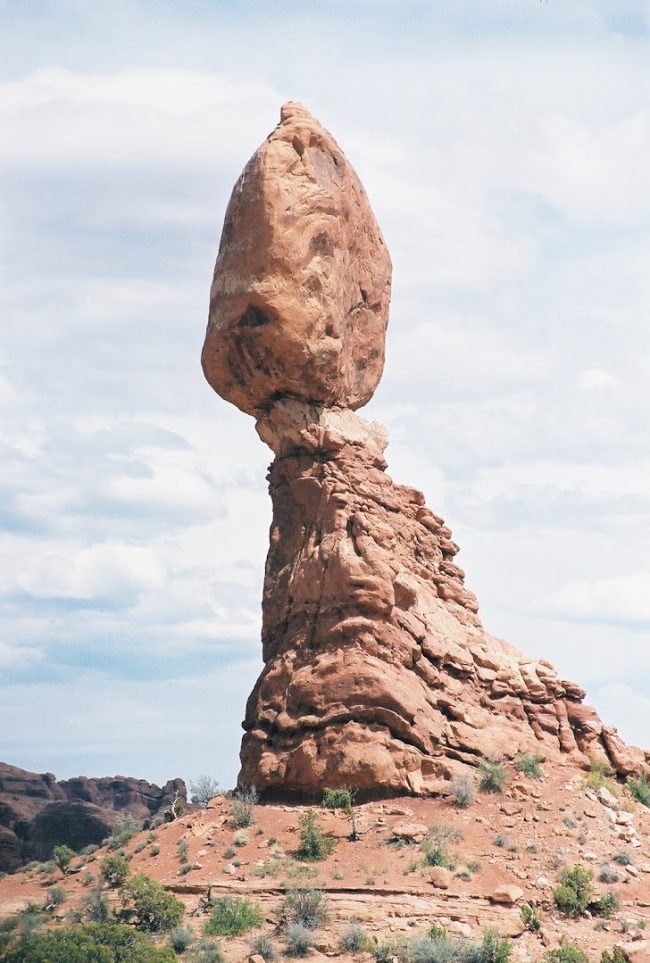

Like Supreme Court decisions, some of his best lines are footnotes or parentheticals summarizing an entire philosophy, like this sermon I could imagine him giving from the top of Arches’ Balanced Rock: “(My God! I’m thinking, what incredible shit we put up with most of our lives—the domestic routine (same old wife every night), the stupid and useless and degrading jobs, the insufferable arrogance of elected officials, the crafty cheating and the slimy advertising of the businessmen, the tedious wars in which we kill our buddies instead of our real enemies back home in the capital, the foul, diseased and hideous cities and towns we live in, the constant petty tyranny of automatic washers and automobiles and TV machines and telephones—! ah Christ!, I’m thinking, at the same time that I’m waving goodby to that hollering idiot on the shore, what intolerable garbage and what utterly useless crap we bury ourselves in day by day, while patiently enduring at the same time the creeping strangulation of the clean white collar and the rich but modest four-in-hand garrote!)”

It’s not wilderness. But it’s still Abbey’s country.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is the editor of FlaglerLive. Reach him by email here.

Ray W. says

Thank you, Mr. Tristam, for this end-of-the-year series of personal interpretations of favorite reads.

I am partial to a recent gift from my oldest sister of William Least Heat-Moon’s Blue Highways, perhaps inspired by Abbey, though I think Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance may have also contributed to the book. The title, Blue Highways, comes from highway maps of that time identifying routes of perhaps remote and sometimes obscure state and county roads with blue ink. Least Heat-Moon took a lap from the mid-Atlantic South through the rural Deep South through the southwestern deserts through to the northwest coast through the upper American Midwest through to New England and then home, all in an old van with a sleeping bag and a portable toilet. Stylistically a journal of his travels, Least Heat-Moon discovers pockets of Americana that was fading away 50 years ago, though I doubt the lifestyles he encountered have been completely lost.

Pogo says

@Ray W.

Had any 5 calendar cooking lately?

Happy New Year

Damien Esmond says

Abby’s Desert Solitare Convinced me in 1993 to drive my ’69 VW Westfalia little camper from NY to all 5 national parks in Utah, Almost died on Pucker’s pass in the Canyonlands NP, as my vehicle was woefully inadequate for the cliff hugging trail, but Wow, what a month of desert exploration, never in my life had I got an opportunity to do that again.

Bill says

I’ve read Desert Solitaire countless times. But one thing always remains. Abbey was kind of a dick.