By Kwasi Konadu and Clifford C. Campbell

The 13th Amendment is having a moment of reckoning. Considered one of the crowning achievements of American democracy, the Civil War-era constitutional amendment set “free” an estimated 4 million enslaved people and seemed to demonstrate American claims to equality and freedom. But the amendment did not apply to those convicted of a crime.

And one group of people are disproportionately, though not solely, criminalized – descendants of formerly enslaved people.

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,” the amendment reads, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

In other words, slavery still exists in America, but the only people whose labor can be enslaved are those convicted of a crime.

To some lawmakers and human rights advocates, that exception is a blight on democracy and the very idea of freedom – even for those convicted of a crime. As scholars of slavery and the histories of African America, our research shows the 13th Amendment’s exception clause reinvented slave labor and involuntary servitude behind prison walls.

Free labor

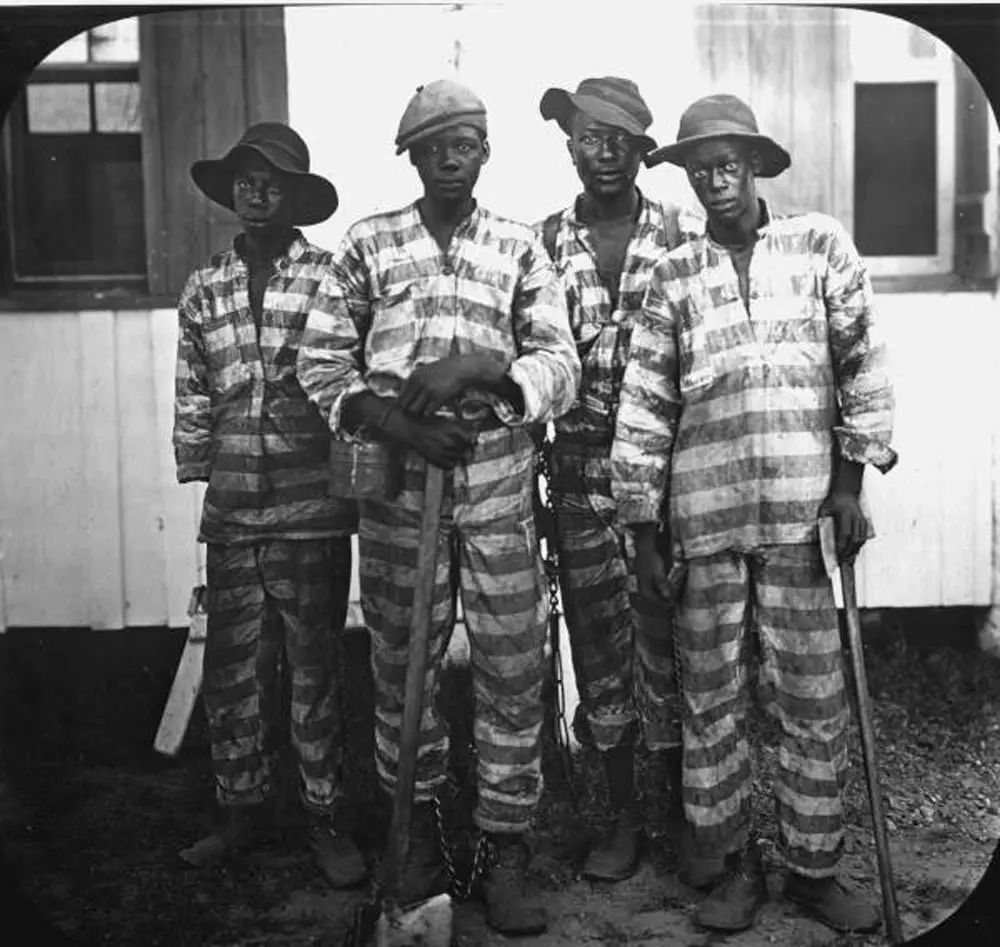

Since the late 1700s, U.S. states have used the labor of convicts, a predominantly white institution that came to include people of African ancestry. Convict slavery and chattel slavery co-existed. In Virginia, the state that had the largest number of enslaved Africans, inmates were declared “civilly dead” and “slaves of the State.”

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that states ended convict-leasing, the practice whereby wealthy farms or industrial business owners paid state prisons to use inmates to work on railroads and highways and in coal mines. In Georgia, for example, the end of convict-leasing in 1907 caused severe economic blows to several industries, including brick and mining companies and coal mines. Without access to cheap labor, many collapsed or suffered severe losses.

Today, the United States has the largest prison population in the world, with an estimated 2.2 million incarcerated people. For many of them, the 13th amendment’s exception has become a rule of forced labor. Over 20 states still include the exception clause in their own state constitutions. Thirty-eight states have programs in which for-profit companies have factories in their prisons. Prisoners perform everything from picking cotton to manufacturing goods to fighting forest fires.

In a 2015 story, “American Slavery, Reinvented,” The Atlantic magazine described the consequences of refusing to work. “With few exceptions,” wrote the story’s author, Whitney Benns, “inmates are required to work if cleared by medical professionals at the prison. Punishments for refusing to do so include solitary confinement, loss of earned good time, and revocation of family visitation.”

In some cases, inmates are paid less than a penny an hour. And many who served their sentences leave prison in debt, having worked without the protections of the Fair Labor Standards Act or the National Labor Relations Act.

In Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana and Texas, penal plantations exist where predominantly Black men pick cotton and other crops under the watchful eyes of typically armed white men on horseback. Some of the largest cotton production prisons are in Arkansas, helping to make the United States “the third-largest producer of cotton globally,” behind China and India.

Ironically, many of the prisons, like Louisiana State Penitentiary, or “Angola,” are located on former slave plantations.

Modern-day convict slavery

Late in 2021, on the 156th anniversary of ratification of the 13th Amendment of Dec. 6, 1865, U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley, an Oregon Democrat, introduced a bill to eliminate the exception. Known as the Abolition Amendment, the resolution would “prohibit the use of slavery and involuntary servitude as a punishment for a crime.”

“America was founded on beautiful principles of equality and justice and horrific realities of slavery and white supremacy,” Merkley said in a statement, “and if we are ever going to fully deliver on the principles, we have to directly confront the realities.”

Based on our research, those realities are steeped in the mythology that America is a “land of the free.” While many believe it is the freest country in the world, the nation ranks 23rd among countries that uphold personal, civil and economic freedoms, according the Human Freedom Index, co-published by the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C.

For U.S. analysts who examine the nation’s constitutional pledges and its actions, the country is less free than often assumed.

Over time, those realities demonstrate a conflict in U.S. history, illustrated by the 13th Amendment. Some states approved the amendment in 1865. Others, like Delaware, Mississippi and New Jersey, rejected it. Free labor was at stake. America embraced the idea of freedom, but it was economically powered by slave labor. Today, the net result is that America is a nation with “4 percent of the planet’s population but 22 percent of its imprisoned,” according to Bryan Stevenson writing in The New York Times Magazine.

Some readers might be puzzled by our discussion of “slavery” in modern life. The Slavery Convention was an international treaty created in 1926, and it defined slavery as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership is exercised.” The “right of ownership” includes buying, selling, using, profiting, transferring or destroying that person. This legal definition of slavery has been upheld by international courts since 1926.

The U.S. government ratified this treaty in 1929. But in doing so it opposed “forced or compulsory labour except as punishment for crime of which the person concerned has been duly convicted,” according to the treaty. The wording of the U.S. government’s opposition is the same as the 13th Amendment. Sixty-four years after passing that amendment, the U.S. government affirmed the use of prisons for forced labor or convict slavery.

It is, then, unlikely the Abolition Amendment will become law despite the authority to do so granted by the second section of the 13th Amendment. A constitutional amendment would have to pass both the House and Senate by a two-thirds majority, then be ratified by three-quarters (or 38) of the 50 state legislatures.

Interest by lawmakers in abolishing modern-day slavery is nothing new.

Back in 2015, President Barack Obama issued a proclamation to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment’s passage. He praised the amendment for “the protections it restored and the lives it liberated,” but then conceded work still needed to be done to fully abolish all forms of slavery.

The interest in the 13th Amendment has also been widespread throughout popular culture. Films, books, activists and prisoners across the United States have for some time linked that amendment to what legal scholar Andrea Armstrong calls “prison-created slavery.”

But given the political realities and economic imperatives at play, free prison labor will persist in America for the foreseeable future, leaving in serious doubt the idea of American freedom – and abundant evidence of modern-day convict slavery.

![]()

Kwasi Konadu is Professor in Africana & Latin American Studies at Colgate University. Clifford C. Campbell is Visiting Lecturer at Dartmouth College.

![]()

![]()

Dennis says

I agree that the prisoners should be made to work within the prison doing jobs that keep the prison going such as cooking, cleaning, and laundry and the like. Anything outside of that should nor be allowed. I often see county prisoners cutting weeds and such around Palm Coast. I always though that they volunteered to do that to get out for a time. Guess maybe I was wrong. I cant say this is racist, because everyone works and if you do the crime, you get to do the time, no matter your color!

Geechee says

You totally missed the entire foundation of the article and what it was explaining. But then again (probably because your Caucasian) in this country you’ve never had to adjust to another’s culture or prejudice. Do yourself a favor and truly research the article before publicly commenting with baseless one-liners.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Codes_(United_States)#:~:text=Black%20Codes%20restricted%20black%20people's,at%20a%20job%20whites%20recognized.

Geechee says

Excellent article. This is what needs to be taught!

https://www.pbs.org/show/slavery-another-name/

Andy Dufresne says

As a white boy that was a former resident in three southern state prison systems over the course of a decade in the 70s and 80s (including a 9 month stint in the aforementioned Angola), I find little to agree with in this article. I cannot recall a single soul, black or white or other, that thought of working while doing hard time as slavery. I worked, ate, slept, showered, laughed, cried right along with black men, and most of the time I was one of very very few whites amongst many many blacks. Most of the rifle wielding men on horseback were black men. I’m probably one of the very few white people on this planet that actually knows what racism is and feels like. It has shaped and molded me into the better man I am today, with first hand knowledge of how utterly disgusting racism can be.

Working was a privilege! Everyone wanted to work. Yes there were the boneheads that didn’t, or some were even too far gone upstairs to be safely allowed outside a cell. Yes they were kept in solitary. But that was their choice. For everyone else, easily 98%, white black green purple blue, we worked. We begged for the work. We begged to go out into the field. I worked the kitchen. I worked laundry. I worked cleaning the dorms. I worked fields pulling turnips and picking peas, rain, sleet, snow, or hundred plus degrees. I dug ditches. I pulled weeds. I made highway signs. I shoveled pig manure. Most of the time it was at .30 a day. That’s 30 cents! In the salad days it was a dollar a day. Simple economy of scale – didn’t need much more money than that anyways. The commissary was priced accordingly. If you wanted to gamble it, or be a loan shark, that was your choice. Just like the crimes that put you there in the first place was a decision you made.

No, I simply do not recall much of anyone thinking that somehow or another the white man is pulling the wool over our eyes and treating us as slavemasters. It just didn’t work nor feel like that. The relationship between the powers that be and the inmates was one of mutual respect and mutual benefit, always. Even the relationship between whites and blacks and hispanics was like that! Things can go south in either direction super fast, for one and all. But everyone I knew (excluding the obvious death row and supermax locations) wanted out of that nasty disgusting cell or dormblock as soon as they could. If you didn’t want to work, or if you thought that somehow or another you were above working, or you even thought you were being treated like a slave, then you went into lockdown. Your life was lonely and miserable and you got less than and were treated less than. But guess what? It’s like that on the streets too!

All of that doesn’t mean it’s “slavery”. Slavery in America in the 1700s wasn’t a choice. In prison in the late 1900s there were no whips. There were no ball and chains. There were no lynchings. Your wife and children weren’t raped and sent off elsewhere. Working in prison no matter the job, and being there in the first place, was a choice.

Geechee says

Uh, number one. Andy Dufresne was incarcerated unjustly and so where most of the black people arrested during the time this article is referring. “Black Code” laws or infractions were set up to fill the need of workers where slavery left off. Obviously, you didn’t read the article nor do the research into where the article came from. I made it easy and posted a link. Well here it is again and another. If your going to sit and type out that much of a comment at least do a little research and take your head out of the sand.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Codes_(United_States)#:~:text=Black%20Codes%20restricted%20black%20people's,at%20a%20job%20whites%20recognized.

https://www.pbs.org/show/slavery-another-name/

A.j says

Jake would you consider Emmit Tills a convict? I read what you said about convict and slavery, perhaps you are right. The reality of convict when it comes to The Black Man is he is lied on by white people mostly white women, the police carry him to jail, they eventually send him to prison based on a lie. It is a little different now but the word convict is different for the races. A black man is lied on and innocent he is locked up, a white man committed the crime they never pursue him. It is this white society always trying to keep Black Men immobile. Jake did you ever hear what white women say about us Black Men, they feel uncomfortable we look suspicious and we fit the description. That is a statement that has caused the death of a lot of innocent Black Men, and a lot are locked up. If you have a chance please read about the Tulsa Riots, The Hanging Bridge, if you haven’t already. Needless to say I don’t particularly care for white people especially white women, I know yall don’t care about my people, look at the murderous history of the white man against the black man. My fore fathers wanted to have a better life this white society hung them, Families of them. Just saying.

Timothy Patrick Welch says

Is work a bad thing?

Nope if its good for freemen is also good for those imprisoned. But only if it doesn’t take freeman’s job.

It cost ~ $20,000 per year to care for a prisoner. So the inmate or their family should be responsible for payment.

I often think your second felony conviction you should forfeit your right to public assistance, and your third conviction your immediate family should also forfeit their right to public assistance.

Just my thoughts

JimBob says

If you were to mention this topic in a Florida public school, you could be fired or jailed. In DeSantis’ Florida convict labor is purely a CRT subject.

Ken says

Spot on… this is reality and the kind of history and truth the Florida leadership wants to sweep under the carpet… could it be that articles like this help to expose current events?

jake says

“A convict is “a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court” or “a person serving a sentence in prison” “Slavery, a condition in which one human being was owned by another. A slave was considered by law as property, or chattel, and was deprived of most of the rights ordinarily held by free persons.” Two entirely different things.

“Hard labor is a form of work which is imposed as part of a prison sentence. The work is compulsory and people are not provided with compensation. The work itself is a form of a punishment. It is considered a form of unfree labor and is practiced in numerous countries around the world.”

“In other words, slavery still exists in America, but the only people whose labor can be enslaved are those convicted of a crime.”

Don’t see the problem with this. As someone mentioned above, compensation for the cost of incarceration has to come from somewhere, why not the person that chose to commit an illegal act.

Geechee says

I like how you remove any link to those who make the laws, and who they enforce them on and why they do so? Perfect example is January 6th. Who determines whether those involved are criminals? It’s a case of “I’m white and I say so.” Meaning the ones in power in this country determine to what degree something is considered a crime. It’s been said “when the United States wants to violate your rights, they pass a new law.” Go back and read the article and links before commenting.