Every day, some 20 people who have served in America’s armed forces kill themselves, a rate 1.5 times greater than for the general population. The rate is even higher for veterans younger than 34. In Flagler County, suicides, of veterans or of others, are at crisis proportion.

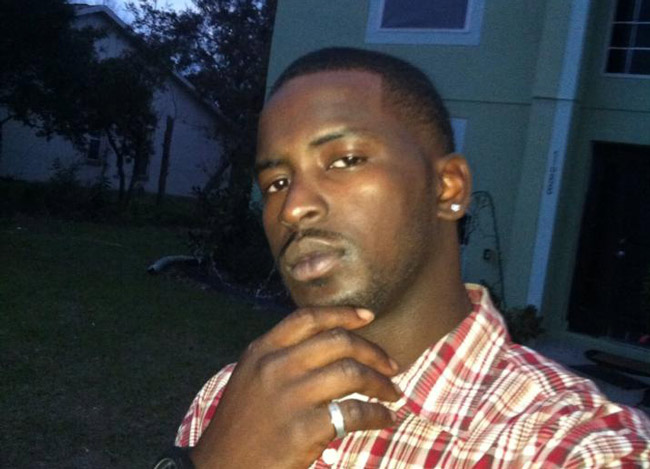

On Nov. 16, Abdul Ganiyu Ayanwale Jr., a 28-year-old Army National Guard veteran, a resident of Palm Pointe apartments in Bunnell, the father to young children, apparently killed himself by gunshot at the home he shared with his girlfriend. That, at any rate, is the Bunnell police’s preliminary finding (it calls it “a possible suicide”)–a finding Ayanwale’s father, who lives in Brooklyn, N.Y., does not share. He is convinced his son would not kill himself.

Ayanwale had served four years in the National Guard but had never been deployed. His last years were overtaken by a series of run-ins with the law and depression, including a 2012 shooting incident that landed him in court. Though he was acquitted, the incident took him out of the Guard. He wanted to get back in, but the death of his mother, precipitating further incidents, interfered, including a June arrest for carrying a concealed firearm and a July arrest for domestic violence. Though his girlfriend signed an affidavit stating she wanted “all charges dropped,” the state was pursuing most of the charges. Days before his death he’d been issued a notice to appear in court.

“He just felt like nothing was working for him, that Florida was cursed,” Dickson said.

“He loved his kid, he loved his parents, he loved to be around people,” his father said. He’d give him advice: “If you don’t have anything to give, smile, because a smile is charity.” And he’d tell him: “Killing people is a sin, killing yourself is a sin. He knows.”

When Ayanwale’s mother died last year, he had trouble coping. He went to New York to be with his father, and when he returned to Florida, for the birth of his son, he met Courtney Dickson, 25, calling her a “ray of sunshine” in his despondency over his mother. They soon moved in together in the Bunnell apartments. She was supporting him, urging him on when their difficulties together didn’t overwhelm them.

“Abdul was very loving, he had the biggest heart,” Dickson said. “He was great with kids even though we didn’t have any children together. My kids called him daddy. He watched them while I worked, he cooked dinner with them, he bathed them, he played hide and seek with them, he helped clean their room, he was very hands-on, my kids’ family loved him.”

Ayanwale had a son and a daughter of his own, who lived with their mother, and Dickson has two daughters, 4 and 6, who were part of the household with her and Ayanwale.

Though he’d tried previously to end his life by taking a kitchen knife to his neck, Dickson said, the day of his death he’d shown no such signs. The day had gone as well as it could, as Dickson remembered it.

“The day that it happened, it was like the perfect day, he told me he loved me, you could never tell that anything was wrong,” Dickson said, “and I’m thinking maybe what I said to him clicked in, that he really had a change of heart.”

Together they’d taken the children to school in the morning. They drove to Deltona, where Ayanwale used to live with his mother, to see a friend of his known only as “Ky.” Ayanwale had told Dickson he just wanted to drop off his resume there. It wasn’t clear why he wouldn’t just email it, and merely dropping off the resume may not have been his intent. Dickson stayed in the car. Ayanwale wasn’t gone long. He reappeared, and they drove on

In retrospect, Dickson believes Ayanwale had stopped at Ky’s house to pick up the semi-automatic .380 caliber handgun found with him after his death.

Later in the afternoon, the friend they’d seen earlier, who picked up the children from school when need be, was trying to drop them off at the Palm Pointe apartment, but no one was opening the door. She called Dickson. Dickson called Ayanwale. He would not answer. Dickson thought he was still asleep. Or tried to think it, anyway: she was aware of his recent depression and messages the day before, a day that had not gone nearly as well.

“All of that sounded good before but now I don’t want anything except to not exist and I wish I never impacted your life because me feeling this way means it was for no reason,” he’d written her. “I don’t want anything out of life anymore except to not have to live it or I would all that stuff for you that I’m not won’t be.” (The texts reproduced here have not been altered from the way they were reproduced in the police report.)

The text caused an argument. She tried to speak things out with him. He texted again: “I know what to do don’t keep us all in prisoned to me go have the life you and the girls deserve with one of the people you are interested in that I been holding you back from instead of being stuck with me this dead weight.” At that point Dickson told him that if he really felt that way, he should move back out, because he was bringing her down. He’;d moved out after the July incident, following a court-ordered no-contact requirement, but they had worked things out.

He then sent her a more conciliatory text, saying he’d be willing to find work. “I’m sorry for hurting you this way don’t be broken please forgive me so I can show you I meant it and I can give you what you want and deserve I even talk to Ky and he said he can get me a job with him working construction I just have to go fill out the application he got for me.” He asked her to take him to ky the next day (having no license of his own).

Police conducted a neighborhood canvas. One of the neighbors of Dickson’s apartment, on the lower floor, reported hearing “a lot of noise coming from apartment 11I” between noon and 2 p.m., and “at one point she heard a loud ‘bang.’” The neighbor thought it was a piece of furniture that had fallen over upstairs. She couldn’t distinguish if the noises were people arguing or something else, but she said it was not unusual to hear loud noises coming from upstairs, or hearing the sounds of kids running around. Other neighbors were not home at the time of the shooting.

After trying him for what seemed like 20 times, Dickson went home to check on Ayanwale. “I didn’t even have to walk in, I could tell from the doorway,” she says. “I didn’t want to keep that picture in my mind.”

Ayanwale’s father claims she called him first, then called police. Police and paramedics found Ayanwale on the bed (half under the blankets) face up, the gun on his chest. An orange and white kitten was sleeping next to him. Responders had to remove the kitten. Its paws indicated she’d walked through Ayanwale’s blood to hop up next to him. His phone was next to him, filled with the missed calls from Dickson, and from others, including his father.

Abiodun Ayanwale says he tried to speak his son at 11:51 a.m. that Friday. His son did not pick up the phone. But they’d spoken for perhaps 40 minutes the previous day, and they spoke every day. His son had been speaking to him proudly about his soon-to-be 1 year old, how he was beginning to stand. “I can’t wait for him to start walking,” his father remembers his son saying.

Dickson frequently spoke with his father too, finding him supportive and good at mediating issues between her and his son. She’d called him that week to speak of her worries that he might do something drastic, but asked him not to tell Ayanwale. She says she went as far as arranging to go with him to a regular Wednesday suicide-prevention meeting in Daytona Beach. But he would not go.

Abiodun then called his son “to check on his state of mind.”

He’s asked point-blank: Is he suggesting that Dickson had something to do with it? “I don’t think she killed him, but she must know something, because Abdul would not kill himself,” he says. “Somebody got into the apartment.” He’s not alone believing in a different cause of death: One of Abiodun Ayanwale’s other sin started a GoFundMe account for–in his aunt Roselyn Northover’s words–“the sole reason of assisting with the high cost of obtaining a private autopsy to prove the true reason for our beloved friend and family,” As of today, the effort had raised $3,000.

An autopsy was conducted by the medical examiner in St. Augustine, as is the norm in such cases. The medical examiner has no direct connection to the Bunnell police, other than that he is hired by a board that includes the Seventh Judicial Circuit’s State Attorney, R.J. Larizza, sheriffs, police chiefs and county commissioners of the four counties in the district. The results of the autopsy have not yet been released.

Dickson, who has been contending with her boyfriend’s death and tending to her children, who miss him, is disbelieving at the way his family has turned on her, not even telling her where his services were held, and the way his father no longer speaks with her. “I didn’t do anything but love him unconditionally and be there for him,” she says. (Ayanwale, hailing from the family of a practicing Muslim, was buried at the Muslim Cemetery of Central Florida in Davenport after services in Kissimmee.)

Reading over the police report, Ayanwale’s father had one disagreement with the narrative.

“While speaking to Abdul Sr,” the report narrative states, “he confirmed his son has made suicidal statements in the past, and that Courtney recently called him about an incident where Abdul attempted to hurt himself.” Ayanwale disputes that. “I know I didn’t say that, definitely didn’t say that, because I wasn’t there, I’m not going to jump to a conclusion and say he’d done that because he’d never done that before,” he says, adding: “I will do whatever I can to seek the truth.”

![]()

The following resources are available for individuals in crisis:

In Daytona Beach: Stewart-Marchman Act Corporation Crisis Center

1220 Willis Avenue

Daytona Beach, FL 32114

Administrative Phone: (904) 947 – 4270

Crisis Line: (800) 539 – 4228

Available 24 hours.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 800/273-8255 (TALK).

If you are concerned for someone else, read about warning signs here. For additional resources, see the Speaking of Suicide website.

Anonymous says

I am very sorry to read this..being a vetran with PTSD , and being assigned to Daytona, so many times appointments are cancelled and I have to call to get medications, there they dont care and will tell me the doctors are overbooked..they are willing to put us in the situation so should be willing to handle us when we come home..sorry for the family…shitty service when you get back

Richard says

Very SAD! To think that we as a nation cannot take care of our veterans, our homeless, our victims of PTSD, etc. etc. etc. BUT will fight tooth and nail over allowing thousands of migrants into our country illegally. Boy have we got a FU’ed country.

Trailer Bob says

So sad…I agree with others, that the VA is not run properly. I too go to the Daytona VA and am not happy, I never get taken care of until things get so bad they decide to check you out. What should happen, is this…enroll us in private insurance and pay the premiums. We waste all kinds of money on these VA hospitals when there are plenty of hospital already. The government cannot run anything without wasting money while not providing the treatments we could get at a hospital or a doctors office just down the road. IF I were not a veteran and had health insurance, I would be in much better condition than I am right now. “Thank you for your service”…my ass.

Steadfastandloyal says

This young man was clearly troubled and yet didn’t take the help offered to attend the counseling, for whatever reason. I don’t believe the VA is mentioned in the article so not sure they can be blamed in this case. When the article says crime “took him out of the guard” does this mean he was dishonorable discharged? If so, he does not qualify as a veteran status

Privilege says

Black man dies by suicide, first three comments aren’t even about the person, the man, only generic Veterans related commentary. Fourth comment is just plain insensitive.

White man dies by suicide in next article and right out the gate he gets a rest in peace. My fellow Flagler county citizens your so biased you really probably don’t even know how you come across.

Janexii Ochoa says

Hello I am janexii one of his step-children /sister for his now 7 year old son and I agree with you even though he was taken out of guard doesnt mean he didn’t go through brutal training and did multiple thing to qualify when he died I was a little kid and I didn’t know what he had going on in his life but now I see and not one feeling about him has changed this man taught me how to ride a bike swim and talk correctly he helped me read he was there for my Christmas school performances and I know no one I possibly going to see this but Abdul was a good man took care of me and my brother and I wont let anyone change that opinion and I don’t care what any of these people say about him or themselves they didn’t know the man personally have a great day