By Ezra Salkin

“I’m going to make an outrageous comment,” said Ivory Johnson, a thin and graying man, standing up just as our class was about to join hands for our customary closing prayer.

When he said this, a barely perceptible nervousness seemed to take hold of the priest and the rabbi—two men of ample shape and similar facial hair, sharing the head of a table at the front of a St. Thomas Episcopal Church classroom.

“I’ve tried to understand the concept of the messiah,” Ivory said. “And we talked about God choosing Abraham. Then we have Jesus. The only difference I can see between Jesus and Abraham is that Abraham had a son. But both came from God and walked upon the earth.” He paused. “So I have a feeling that both were one and the same.”

If the scene had taken place in a bar instead of a church, it could have been the start of a joke. But Rabbi Merrill Shapiro and Rev. Robert Elfvin decided that an exploration of Ivory’s remarks would have to wait for the following week, along with other comments that ranged somewhere between thoughtful and off the wall. “Think about it,” Ivory said with a shrug, to a roomful of people interested in talking about the Bible, whether they believe in its precepts or not. The group then linked hands and the priest led the class in a prayer that was gracefully non-sectarian.

No comment is out of bounds in this interfaith class, held weekly at St. Thomas Church in Palm Coast since December. Many of Shapiro’s observations might sound unconventional to the group, most of whom embrace a Christian perspective—the class does take place in a church—when it comes to understanding the Old Testament, or “the First Testament,” as the rabbi calls it.

One example: God actually wanted Adam and Eve to eat the apple from the Tree of Knowledge. This makes the carefully plotted Christian notion of original sin complicated, and is a good illustration of the dichotomy of perspective which makes the class interesting. When seen in a positive light, according to Shapiro, the tree effectively symbolizes the centrality of literacy in Jewish culture. If good literature is often the exploration of gray areas, it’s through this lens of ambiguity that Jews seem to view their texts.

When it comes to historicity in Judaism, which is to say, whether or not Noah actually loaded a boat full of two of every animal in the world, or whether Jonah was swallowed by a whale, the rabbi says it isn’t all that important. If it’s all fiction, Shapiro says, “Don’t sell fiction short.”

That sort of dialogue is typical of the weekly class, which grew from a one-time invitation to Shapiro by the Rev. Dr. Frank Hull, the rector of St. Thomas, tapping Ivory, a friend and political colleague of the rabbi’s as an emissary, to speak to his congregation about Genesis from a Hebrew perspective. The class went so well that Hull invited the rabbi back to explain the Torah, also called the Pentateuch, which are the five books of Moses that comprise the beginning of the Hebrew bible. Hull asked Elfvin to help guide and balance out the class at about that same time.

“There can be a tendency among some of the more fundamentalist Christians, though not many Episcopalians, to think that God wrote the Bible in English and sent it down by Federal Express,” says Hull. “And because it is claimed that the New Testament ‘replaces’ or ‘supplants’ the Old Testament—which is an over-simplification—that therefore you can just ignore it except for a few Levitical laws that fit your current opinions about life or society.

“Knowledge is a good thing,” Hull continues. “A rabbi has probably spent more time studying the Pentateuch, especially in Hebrew, than any priest. Many clergy have never studied much, if any, Hebrew at all. From an Episcopalian point of view, knowledge is always valued in and of itself. So, from my point of view, why not invite a rabbi?”

And that invitation has led the group, which has expanded from the original seven parishioners to more than 20, to discuss such things as the Jewish concept of sin. There’s no hell or devil in Judaism, says Shapiro. Sometimes a serpent is just a serpent. There are no angels, at least not as Christians depict them. In a recent class, Shapiro called the 1993 Bill Murray movie “Groundhog Day” and its notion of repentance—“You do something wrong and you must repeat it over and over again until you get it right”—one of the most religiously significant films of modern times, more so even than the 1956 Charleston Heston version of “The Ten Commandments.” (The very title is a misnomer, as there are in fact 613 commandments, a fact that never fails to impress the class.)

Not surprisingly, given our polarized society, religion occasionally intersects with politics in the class. As the whole of Judaism tends to lean progressive, what does the rabbi make of Christian conservatives who often reference and quote the Torah to support their positions?

“They read the Old Testament, they do not read the Hebrew Scriptures,” says Shapiro. “They often misquote the bible, but then they often misquote the founding fathers of the United States. I know people can take our tradition, can take our texts and can read them anyway that they like. They’re often deeply in error.”

In February, Shapiro wrote a letter to the editor of the St. Augustine Record, titled “Keep Creationism out of state schools,” in which he criticized Governor Rick Scott’s appointment of Andy Tuck to the state Board of Education. Shapiro wrote that the Creationism that Tuck “wishes to be taught in place of evolution is a religious doctrine, not science!” He added, “The Bible and religious instruction have important positions in our lives but do not belong in taxpayer-supported schools and certainly can’t be called ‘science.’”

Shapiro, who is president of the national board of trustees for Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, has been involved in many efforts to foster interfaith dialogue across the country. “It often fails because people of various faiths sit in a room and have nothing to talk about,” he says. “Very often, both sides enter with a superior attitude, like ‘I’m going to teach these heathens the right way to live.’ But here, we’re not even involved in interfaith directly, we’re involved with doing a third thing, and that’s trying to understand how the biblical text speaks to us from across the millennia.”

Elfvin, 69, who during the class sometimes breaks down New Testament language into the Biblical Greek, says the sessions might not be as successful in the churches of many other Christian denominations. A life-long Episcopalian, Elfvin has spent much time in other churches ranging from Catholic—because he has “affection for it”—to Charismatic. Of these Pentecostal-style congregations in which the worshippers speak in tongues, the reverend confesses that he “likes far-out things.”

In a Southern Baptist church, for example, this class would be “a very difficult sell,” says Elfvin. “It would be very unusual because the emphasis (among Southern Baptists) is ‘Are you saved? Do you acknowledge Jesus as the lord and savior?’” That premise would undoubtedly result in an uncomfortable atmosphere for the Jewish members of the class.

It’s not likely that the class would go any more smoothly in many Roman Catholic settings, says Elfvin. He recalls a time when he was asked to do some guest preaching at a Catholic church in Iowa. Afterwards, a woman parishioner came up to him and said, “I hope we’re not going to do this all the time. I didn’t listen to a thing you said.”

“Well, why?” he asked.

“Because you’re not a real priest,” she replied.

“I dare say that person wouldn’t be open to a Jewish dialogue. She wasn’t even open to another Christian dialogue,” Elfvin says.

As it happens, the Episcopal Church, part of the worldwide Anglican Communion, is Protestant, yet carries over certain Catholic traditions.

“Anglicanism always put up with that dual understanding,” says Elfvin. “You can be a very reformed Protestant person and still be an Anglican. You can be a very Catholic person and still be an Anglican. It’s a church that embraces all people where they are and doesn’t insist that they all see it exactly the same way. And that was always the genius of Anglicanism.”

Elfvin moved to Palm Coast about two years ago, retiring from his parish in Iowa after being stricken with vasculitis, the same disease that recently claimed “Groundhog Day” director and co-screenwriter Harold Ramis. Like Shapiro, Elfvin wasn’t entirely certain about what he was taking on when he stepped up to lead the interfaith class.

“At the rate we’re going, I don’t know if both the rabbi and I will live that long to finish it,” he says, noting that, as slowly as Shapiro is taking the class through Genesis, “I can go even slower with the New Testament.”

According to Shapiro, our group, in which I was one of the younger participants, could have found itself walking on eggshells, but that hasn’t happened—yet. As more New Testament is brought into the discussion, specifically the Gospel of John, Shapiro suspects there could be some awkward moments ahead. But that will only make the class more meaningful, he says. One example is John 8:44, where Jesus uses some very choice words to castigate a group of Jews.

“Ultimately, we’ll be approaching some topics that are difficult to deal with and confront,” says Shapiro. “Rather than dodging issues, this will allow us to confront some of the ways in which the church has reacted to Jews and some of the ways in which Jews have reacted to the church.”

Class member Ivory Johnson, who’s nearing 80, says he encouraged Shapiro, who in 2009 retired from Temple Beth Shalom, Palm Coast’s one synagogue, to make the class a regular event. Johnson, a retired accountant, was the treasurer of the Flagler County Democratic Club when Shapiro was its president, before the group was dissolved in favor of more localized units.

Johnson first met Rabbi Shapiro about four years ago at a meeting related to Amendment 8, which sought to remove a prohibition restricting the use of vouchers to channel taxpayer money into private religious schools. Shapiro was against the amendment, and that impressed him.

“I was surprised that a rabbi would do that, because they benefit from this thing. A religious school would benefit from this funding. But he was against it because of principles,” Johnson says. (The amendment failed.)

Johnson has come a long way at St. Thomas, he says. His wife, Catherine, is a “cradle” Episcopalian, who also attends the class, but Johnson says he has always been “one of those non-believers.”

“I wasn’t an atheist. I just didn’t believe in organized religion,” he says. “I thought that religion did more harm than good.”

Historically, he says, religion has always been one of the great supporters of violence, which, as a Korean War veteran, he abhors. “I hated it. I thought it was the worst thing man could do to one another,” Johnson said.

But it was Catherine, Johnson says, who finally got him out of bed and into church on Sunday mornings. “I said, my wife is an excellent woman—why can’t I see what she’s really into?” Now, he says, “St. Thomas is one of the best things to ever happen to me.”

Johnson’s beef with religion, or religious people, always seemed to be with people of the faith he was born into, Christianity. For example, he had a devout Baptist cousin whose wife left him for a deacon in their church. He had many positive experiences with Jews, particularly with many of the Hasidim, with whom his family shared an apartment building on New York’s Lower East Side in the 1960s.

The Johnsons were among the few non-Jews, and among the few African Americans, living in the building, says Deborah Wells, Johnson’s 49-year-old daughter, who also attends the class. As a child, she and her brother used to hold the door open for the Orthodox Jews during their Sabbath—when they were forbidden from opening the doors themselves because it’s considered an act of work—for the price of a quarter. She says that a Jewish neighbor cared for her when she was stricken with meningitis, and may indeed have saved her life.

Two years ago, Wells boarded a train to Prague during a visit with her son in Europe. As the train passed through the vicinity of the Theresienstadt concentration camp, she says she entered a catatonic state. She suddenly found herself traveling in a cattle car, in a different time, filled with despair. Wells believes she channeled the spirit of a Jewish woman living out her death trip during the Holocaust.

Wells is outspokenly agnostic and has no qualms about expressing her skepticism during class. “I felt like I was insulting people in the group because I don’t follow the traditions of bible study class, which is everybody must believe in the bible,” she says. “Otherwise you spend the whole class debating the veracity of the book, and that’s not the point of bible study. But there is a place for opposing views like mine when we change from bible study into an interfaith council, which is where I think the class is going and better serving its members.”

Aurora Hoffman Mercer, an original member of St. Thomas’s traditional bible study group, says, “I love the bible because you see there’s nothing new under the sun. Murder, adultery, you can see all this was happening then, too.”

A social worker who also does Christian counseling at the church, Mercer began coordinating the interfaith class, trying to keep everyone on task, after the presiding priest stepped down due to illness. As for that often uncomfortable blend of politics and religion, Mercer says that while many in the group are registered Democrats, she is “a very conservative Republican,” who always carries a gun (though not in church).

“It shows the openness of how we are there to learn and study and talk about issues and be respectful of one another,” she says. “We really try not to put politics in there. What we try to do is biblically talk about how we should behave as human beings.” Occasionally, politics do seep in, however, and then, she says, “If good things come and help us all understand a person’s viewpoint, then that’s terrific, but we’re not a political group and we’re not there to talk about politics.”

The great uncle of Mercer’s husband happens to be Bernard Baruch, a renowned early 20th century Jewish financier, philanthropist and adviser to presidents. Mercer says she hopes the class will only get more diverse, with more points of view and experiences added to the mix.

Connie Goldberg, 79, a retired family practitioner and Cancer survivor, had to attend two different Sunday church services while growing up along with her seven siblings. Her father was a devout Episcopalian but her grandfather on her mother’s side was a minister in a small and contrastingly simple congregation, a church almost completely absent of liturgy, called Brethren. In that church parishioners meditated on bible verses and contributed spontaneously.

By the time she got to college, she expected to be done with religion but was surprised when she felt called back to church. After being spoon-fed so much Christianity, “Learning about the Jewish way of thinking is really great,” she says.

Another class member, who knows something about religious intolerance, is Charlotte Siegmund, 83, who grew up in southern Germany during World War II. Her family, who had moved to Germany from the U.S., was Lutheran while nearly everyone in their German town was Roman Catholic. Because Siegmund and her sisters didn’t go to Mass, the other children called them “devils.”

“Maybe God will forgive you. Maybe not,” she said one day in class. The American experience of being around Jews has been more than enlightening, she says. She remembers the day she discovered that the American Jews who later surrounded her in New York were speaking Yiddish—not “terrible, terrible German.”

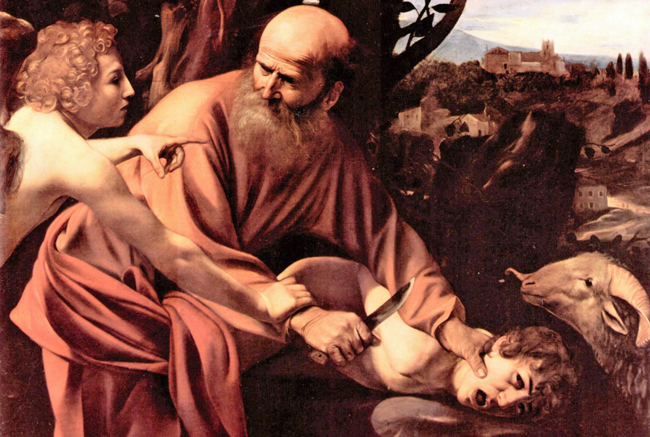

Joan Grube, a linguist by “hobby and education,” is one of the Jewish members of the class. As the group read of Abraham preparing his son, Isaac, for sacrifice, Grube wanted to know where Issac’s mother Sarah was in all this, a pertinent question rich with implications about patriarchal assumptions and the role of women.

“That is a novel waiting to be written,” was Shapiro’s short answer.

When she retired as a high school English teacher, Grube was determined to learn Hebrew, and began taking lessons with Shapiro, in a women’s class that was small enough to rotate among homes “like a floating craps game.”

As a non-observant Jew, Grube found that her late-in-life Hebrew lessons led to a deeper interest in her ancestors’ religion and the Old Testament. She recently held a weekend-long celebration at her house, honoring the installation of openly gay rabbi Rabbi Zev Sonnenstein at Temple Beth Shalom. (The Episcopal Church has been at the forefront of churches that have decided to ordain gay priests, though policies differ from diocese to diocese. Currently, the diocese of Florida does not take part in this practice, says Hull.)

At St. Thomas, Grube has found the opportunity to also learn about Christianity. “I knew nothing about the New Testament except what you learn through literature and what you learn being in America and having non-Jewish friends, of course,” Grube said. “But I’m by nature a student and a teacher. If there’s a course anywhere, sign me up, I’ll be there—whatever it is!”

Like many American Jews, she has a Christian friend who vocally expresses concern for Grube’s soul (an experience that she and I share). Grube has been trying to get her friend to become a regular member of the class.

Several members of the class have remarked on the violence in the Old Testament. In Genesis, God destroyed the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah for the “iniquity” of its peoples and, in an act that seems improbably cruel, he turns Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt for glancing back as everything she’s ever known is destroyed by hellfire and brimstone. The reason: God had told Lot and his family not to look back.

“Rabbis today speak of immobility and inflexibility within Judaism,” Shapiro said one day in class. “All Jewish law and thinking can either be like Lot’s wife, locked in stone, immobile, or we can recognize that our thought processes, our law, our understanding of people is always flexible and growing. There are some who are anchored in law: This is what it was, this is what it is, this is what it must be; and there are other people who are much more flexible.” What is most significant about Lot’s wife, said the rabbi, is that she was more preoccupied with looking back than forward.

The class at St. Thomas is continually growing, which might soon necessitate moving it from the meeting room to the parish hall. All are welcome: If you are interested, it won’t be hard to find a spot at the table.

muse says

I recently stumbled across Zoroastrianism while reading up on ancient civilization and was not surprised to find out that it not only predates Judaism, but that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are spinoffs of this religion. Zoroster, the creator of Zoroastrianism preached one god as creator of the universe, of good and evil, and of sin. And he declared himself a profit of this one god. Interestingly, too, not long ago I read the Epic of Gilgamesh (written 8,000/6,000 years ago in ancient Sumer) and was befuddled to read about the great flood and other biblical stories. Today, this is called plagiarism.

NortonSmitty says

I cannot believe you would print such a blasphemous article on this sacred day. The day we all celebrate the undeniable occurrence of the blessed day when our Lord and Savior gave his life to save us all from Original Sin. And for his efforts, they nailed him to a cross and flayed him until his manly body finally died. And the evil ones then threw his decaying carcass into a damp and lonely cave, sealing it with an immovable rock..

But Lo and Behold, three full days later, the stone miraculously rolled aside! And our Lord and Savior stepped aliveout of that dank cave! And if he sees his shadow, we get six more weeks of Winter.

And gives me my second favorite Zombie holiday every year. Life is good.

THE VOICE OF REASON says

Clever, but flawed premise. And here’s why:

Easter is determined as the Sunday following the Paschal Full Moon, which puts it anywhere between March 22 and April 25. But the vernal equinox, which marks the first day of spring, is almost always March 20 (occasionally March 21).

So whether he saw his shadow is immaterial because Spring would have already sprung. This year, for example, Spring started on March 20 and Easter was on April 20.

But more importantly, I’d be interested in knowing what tops your list of Zombie Holidays?

NortonSmitty says

Halloween, of course.

Will says

It’s wonderful that this is happening here in Flagler Co.

GY says

Thank you St. Thomas and Rabbi Shapiro for teaching the truth about love as it should be understood in all faiths.

Larry says

Sounds like they need an atheist to balance it out.