The charges Stanley Wykretowicz faces could, if he’s found guilty in his trial this week, send him to prison for 30 years. He’s accused of brutalizing his 2-year-old niece in his Palm Coast home in February 2014, where his niece and his then-13-year-old daughter lived at the time. He was the girl’s sole caregiver. faces a first-degree felony and a second-degree felony. He’s always claimed his innocence, attributing the girl’s unresponsive condition to illness when he took her to Florida Hospital Flagler.

That, and falling twice in the bathtub: the 2-year-old was significantly bruised on her forehead, her shoulder, her stomach and her back. But he said that had nothing to do with her illness.

A beating was very much part of the first day of trial before Circuit Judge Dennis Craig in a Flagler County court today, after a jury of six men and one woman (one of them an alternate) was seated on Monday. But it was a beating the prosecution was suffering at the hands of the defense, a trio of lawyers who flanked Wykretowicz, 41, like a posse throughout and kept Assistant State Attorney Joe LeDonne off balance and on his heels for most of the day—an unusual position for a prosecutor whose trial wins can usually be gauged within an hour or two of opening arguments.

Not this time.

The day ended after the prosecution’s four witnesses had delivered far less than a blow to the defense, let alone a fatal blow, and often walked into the defense’s explicit strategy of making it seem as if no one knows the what, the when, the who, the where and the how of the little girl’s predicament (except, of course, for Wykretowicz, who is not required to testify).

When the jury was dismissed for the day, LeDonne announced to the judge that he might be calling Wykretowicz’s teen-age daughter to the stand on Wednesday.

That was the first time Aaron Delgado, the defense’s lead lawyer, looked surprised—either because it was an act of desperation on LeDonne’s part or a tactical move Delgado had not expected.

“That testimony is fraught with peril for a mistrial, more so than the usual because she’s an accusing witness in a separate case,” Delgado told the judge, asking for a “proffer,” a sort of elaborate sidebar to the trial where the two sides actually cross-examine the witness but without the jury present, to establish boundaries to what the witness may or may not say before the jury.

The reason the daughter’s testimony could be “fraught with peril” is because she is at the heart of another child abuse case involving Wykretowicz: almost a year to the day when he brought his nice to the hospital, he was charged with new felony child abuse and battery by strangulation charges, both third-degree felonies, after his daughter reported being physically hurt by Wykretowicz’s girlfriend (who also faced similar but not identical charges) and constantly demeaned by Wykretowicz to the point that she was cutting herself.

The jury in the present case is not hearing any of this, nor can that backstory be made part of the testimony against Wykretowicz should his daughter testify. It’s part of a list of things the jury won’t hear, including the fact that Wykretowicz’s niece, who recovered after three surgeries, is no longer living with him, and a no-contact order against him is still in effect regarding both girls. He is allowed to see minors only on Christmas eve and Christmas day, in supervised visits. (He’s out on $150,000 bail on the present case. A half dozen friends or members of his family sat behind him in the courtroom).

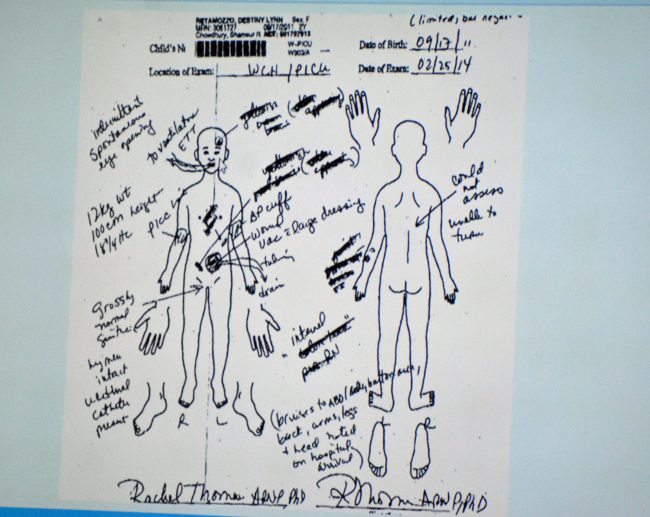

Even in the case involving the 2-year-old, a key witness, Rachel Thomas, an advanced registered nurse and member of the Child Protection Team at the University of Florida who determined that the girl had been abused, was not allowed to utter that conclusion in front of the jury. The defense successfully argued that she could not be considered an expert witness. (Never mind her doctorate in nursing, her 15 years of training in child abuse and neglect and the more than 50 times she’s given expert testimony in such cases: the defense was relying on a section of Florida law, remarkably out of step—and sexist—but enduring, that can be interpreted to limit expert testimonies in medical cases to physicians).

“My opinion was that she suffered blunt force abdominal trauma from physical abuse,” Thomas had said in a proffer, out of the jury’s hearing. “If I was speculating I would speculate a kick or a punch but not from a fall,” she said of the girl’s condition.

“I’m not letting her testify to say that it’s child abuse,” Judge Craig said, after hearing the defense claim it had not deposed Thomas nor prepared for her as an expert witness. ”I’m also concerned with her opinion that it was done by blunt force trauma,” because that infers child abuse, he said.

LeDonne was visibly, audibly frustrated. “There’s no other way for her to testify” he said. “Her opinion is it’s traumatic injury, that it’s not any kind of infection.”

In vain. One of the two most important witnesses of the day for the prosecution was muzzled where it mattered most. It was an unlikely but key victory for the defense early on.

Knowing that, the defense could then craft its cross-examination to exploit the obvious hole—to make Thompson sound less convinced, and therefore less convincing to the jury, that her observations were anything more than accurate but disparate observations, especially when Delgado seemed to undermine her credibility by harping on peripheral issues: did she not read a pathology report? Did she not make that part of her final report? How could she not? Practitioners don’t read every imaginable report there is on every case of course (she called the pathology report “one tool in the arsenal,” and described pathology as expertise “on the cellular level”), but juries don’t know that, and lawyers know that with juries it’s perceptions that count, not whether a protocol was properly followed, as it very much was in Thompson’s case. (Thomas explained that the pathology report may have been uploaded in the system after she was required, by the Department of Children and Families, to file her own report.)

Delgado had made his point. “As we sit here you really have no idea as to how the perforation occurred,” he told rather than asked Thomas.

“I have an opinion but I’m not allowed to render it,” Thomas replied, by then more curt than she had been at the beginning of the testimony.

Medically, the focus of the case is not the external bruises the girl showed when brought to the hospital, but the perforated part of her intestine the pediatric surgeon discovered during the first of three surgeries. There’s no disagreement on either side as to the medical reason behind why the girl was unable to digest food, why she was throwing up—as her uncle described it—for two days, even why she had become comatose when he brought her to the hospital: the perforation had led to the spillage of stools inside her belly, essentially starting to poison her with sepsis, or an infection, and parts of her intestines were filled with bacteria and inflammation and had to be cut out.

What caused that devastation is at the heart of the case. The prosecution says the perforation was the result of blunt force trauma—a stomping or a beating, or something willfully violent. The defense says it’s an infection from within that has nothing to do with beatings or falling in the bathtub. It’s “Necrotizing enterocolitis,” the medical condition that replicates symptoms the girl developed.

Except that that condition, both Thomas and the surgeon who operated on the girl said to the jury, does not happen in girls her age. It’s a condition that afflicts only pre-mature babies and babies in their first weeks of life. If it happens in older children, it’s extremely rare.

Delgado’s opening argument made two points: that contrary to the prosecution’s claim that the harm to the girl was inflicted from outside in (in other words, by her uncle), it was contracted from inside out: her uncle had nothing to do with it. The defense’s chief evidence is a pathology report that replicates that claim, though not the leap that Delgado would keep making through the first day: that since the pathology report’s conclusion is that an infection had developed, there had been no blunt force trauma. That claim is to be made Wednesday by an expert witness the defense is paying $2,000 to appear, and to say, in Delgado’s words, “absolutely no blunt force trauma.”

Still, at every turn, the defense’s approach proved more effective than the prosecution’s, starting with the two sides’ overall strategy. The defense on one hand was content to drown the jury in the murk of medical doubt and a bombardment of unfamiliar medical terms and information, knowing that it lends the approach a semblance of expertise even if every claim could be mercilessly and endlessly debated by a medical board.

On the other hand it undermined the credibility of witnesses by seizing on minor inconsistencies. Flagler County Sheriff’s detective Annie Conrad, who worked on the case but was not its lead detective (it was never made clear why the prosecution never called detective Mark Moy, who was), had also not read every single document or report filed in the case: “Nobody seemed to share information with one another,” John Reed, another member of the defense team, told her in reference to documents on the case at the sheriff’s office.

She had not read Wykretowicz his rights through various conversations because he was forthcoming and not under arrest (nothing out of the ordinary, but enough for the defense to raise questions in the jury’s mind, as was made evident by a juror’s question later). Reed then tried to swing her into a defense witness when he asked her whether, through numerous interview with her and others at the sheriff’s office, Wykretowicz had ever changed his story. He had not, Conrad said, though she couldn’t day that in and of itself that’s not necessarily proof or disproof of anything, as detectives well know. (Wykretowicz used to be a jail guard in Orange County, N.Y.) And Conrad, too, did not recall seeing that recurring pathology report. (Sam Masters, the third attorney on the defense’;s team, did not ross-examine but sat next to Wykretowicz throughout, explaining the process when necessary.)

The prosecution did not seem to have a strategy other than to let what it projected as the obvious tell the story—the images of the bruised and comatose child at the intensive care unit (though the judge forbade showing the child intubated), the medically indisputable claim that “falling on the side of a bathtub does not cause a perforated colon,” and the fact that she was brought to the hospital “lifeless, she was blue, she was nonresponsive, and that’s why we’re here today.” But there was no further connection between the seemingly obvious signs of trauma and the prosecution’s claim that Wykretowicz was the cause. The prosecution, in other words, was hoping to skate on the visceral aspects of the case rather than present unassailable evidence. And it had no plan B when its witnesses were forbidden from lending some expert credibility to the seemingly obvious. So the “seeming” qualifier—the equivalent of reasonable doubt—was never removed.

The prosecution made its strongest case with Daniel Robie, the physician who operated on the little girl, and whose leadership positions and resume would fill a booklet. He provided conclusions Thomas could not: “To me this looked like an injury that occurred from some type of a blunt force and damaged that piece of intestine,” he said. “Over the many years that I’ve been practicing I’ve seen this on more than one occasion,” including, he said, “blunt force actually caus[ing] a hole to occur from that injury, in the intestine, and have no other injury at all. And I’ve seen that many times in my career.”

Delgado handles witnesses like a semi-automatic tenor, firing questions staccato-style in short, declarative statements without preambles or qualifiers, tunneling witnesses into equally short answers and zapping them shut if they stray. He couldn’t pull it off with Robie, who spoke to his own rhythms and knew his medicine (and let Delgado know it).

Yet Delgado got Robie to concede that the bruising on the girl’s skin was not caused by the injury, for him to seem dismissive of pathologists in some cases (“to me the live patient at a bedside gives you a lot more information than any tissue in formaldehyde”), and to concede that he could not say with certainty what kind of trauma the girl had sustained if indeed it was trauma. The difference was slight but effective, if also disingenuous on Delgado’s part: by asking the question Delgado was himself conceding that trauma might have taken place, but he was sowing doubt in the jury’s mind by making the doctor seem less than knowledgeable on the cause, even if no one who hadn’t witnessed it could or would specify what form of trauma had been used. Similarly, he got the doctor to concede that while he’d initially insisted that whatever traumatic event had happened to the girl couldn’t have been more than a day or two old, it could after all, have “possibly” been more than 48 hours old.

No matter how contrived the approach often seemed, Delgado was underlining his recurring thesis: that the prosecution could not establish the when, the where, the why, and so on, and betting that the jury (or the prosecution) would not dig deeper than the surface appearances of minor contradictions and inconsistencies.

And LeDonne let him get away with it: when Delgado was done with the surgeon, the prosecution’s strongest witness, LeDonne had no further questions. It was 23 minutes before 5 p.m. The decision looked more like a surrender to a tough day than anything else, and possibly to more than just a day.

Dano says

What do you expect from a non high profile trial that took nearly 3 years to get prosecuted?

Todd S. says

They say Delgado is the best criminal defense attorney around…

Jenn says

I truly hope and pray that Justice is served these two girls he should be locked up for life