By Lincoln Mitchell

In 1959, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev visited San Francisco and members of the International Longshoreman’s Union greeted him with cheers, newspaperman Frank Coniff quipped: “This is the damndest city. They cheer Khruschev and boo Willie Mays.”

It was the height of the Cold War and, for Coniff and many of his readers, there was no better symbol of America than Mays. At that time, Mays was a 28-year-old centerfielder for the San Francisco Giants and the best ballplayer in the world, and he was occasionally booed by fans of his own team.

A decade before that, Mays was playing for the Birmingham Black Barons, a Negro League team near his hometown of Westfield, Alabama, while still in high school.

Mays, who died on June 18, 2024, at the age of 93, was not only the greatest baseball player of the last 80 years, and quite possibly ever, but he was an enormously important figure in American sports, culture and history. His journey from the segregated Deep South of his childhood to being honored by President Barack Obama with the Presidential Medal of Freedom spans much of America’s racial history in the 20th and early 21st century.

In 2009, Mays traveled to the All-Star Game, in which he had played a record 24 times (from 1959-1962 there were two All-Star Games a year), on Air Force One, where he told a rapt and smiling President Obama how much it meant to him after “growing up in Birmingham” to see an African American elected president.

Mays repeated several times how proud he was of Obama. The president responded, “If it hadn’t been for folks like you and Jackie (Robinson), I’m not sure I would have ever got elected to the White House.”

‘Racism and racial epithets’

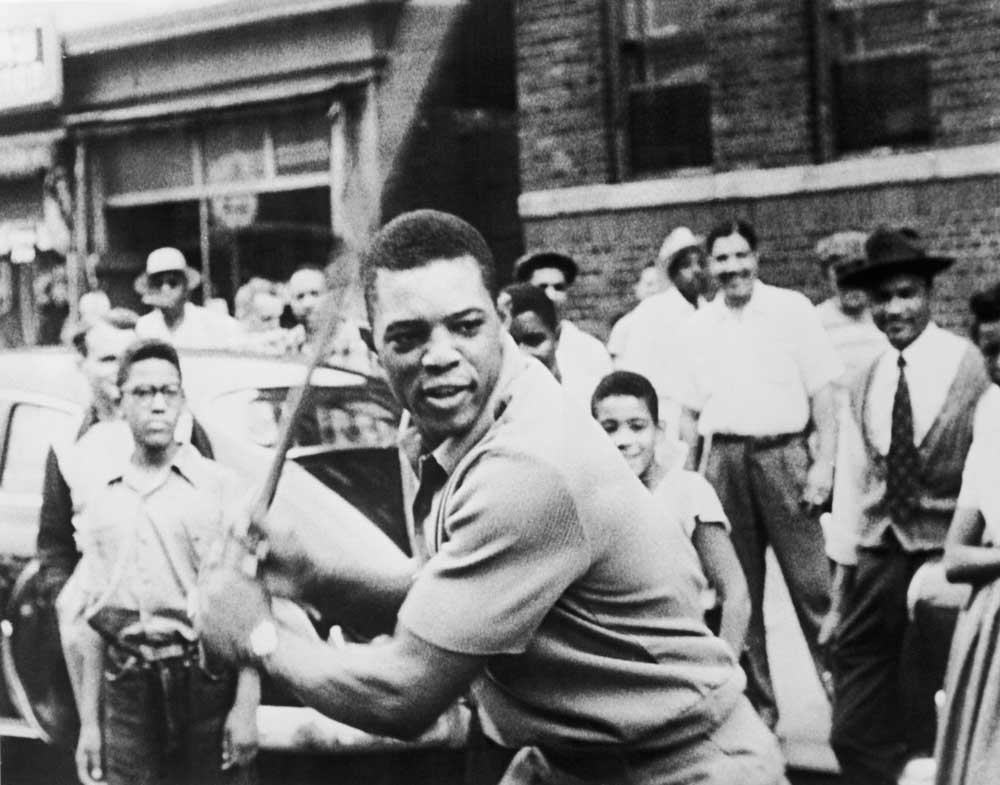

Mays began his career with the New York Giants in 1951, four years after Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He became known as the “Say Hey Kid” because of his youth, exuberant style of play and habit of greeting people with the phrase, “Say Hey.”

Bettmann/GettyImages

In those years, the integration of the National and American Leagues was still in its earliest stages. There was an informal rule limiting each team to no more than three non-white players. Many teams, including the Yankees and the Red Sox, were still entirely white.

Although the Giants played on the northern edge of Harlem, where Mays lived early in his career and was widely beloved, when the team traveled to more southern cities and during spring training in Florida, Mays was subject to the same racism and racial epithets as Robinson.

The centrality of baseball to American culture during this period made Mays even more significant. This was still a time when baseball players were by far the most recognized athletes in the U.S. and when much of the country tuned in to the World Series every fall.

By the late 1950s, Mays was, along with Mickey Mantle, the most famous ballplayer in America. For decades it has not been unusual for African American athletes to be broadly admired, but Mays was the first. Mays’ appeal to all fans was not just due to how good a player he was, but also the panache with which he played the game, wowing fans with basket catches and daring base running, as well as a public personality that was outgoing and friendly.

Representing … with a ‘regal stature’

Robinson was a trailblazer and a unique figure in American history, but Mays’ impact on the culture was broader and at least as important.

Frank Guridy, a professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University, summed this up: “Mays was this Black mega-superstar in this country who was somehow able to transcend his background as somebody from the Jim Crow South to become appealing to white America. He was able to be Black and represent the Black intervention in the sport, while maintaining a regal stature that is appealing to all people.”

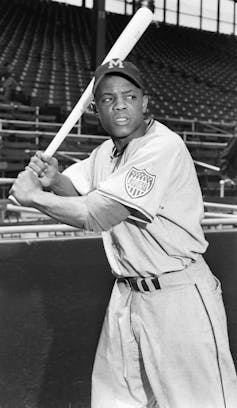

Bruce Bennett Studios/Getty Images

During the 1960s, when Mays was the best and most famous baseball player in the world, he was criticized by some for not being radical or outspoken enough. That criticism seems a bit unfair now.

Unlike many other great African American athletes of the era, like Bill Russell, Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Wilt Chamberlain, Jim Brown or Robinson, Mays was a product of the Deep South and, on some level, carried that trauma with him.

It is often overlooked that, for the last decade or so of his career, he was deeply respected by almost all African American baseball players because of his ability and his role as an early trailblazer. As the best player, with the most seniority, on the San Francisco Giants in the 1960s, he set a tone and kept the peace in what was then by far the most diverse clubhouse in baseball.

Daniel Shirey/MLB Photos via Getty Images

Because Mays played in San Francisco for the Giants from 1958 until he was traded to the Mets, and back to New York, during the 1972 season, his off-the-field activities did not always receive the attention they deserved. However, for decades he worked with youth in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point community, a largely African American neighborhood where Candlestick Park was located.

Transcending racist history

Mays, who played his last game during the 1973 World Series, was a baseball star at the very end of the period when baseball was a massively important cultural institution, and at a time when baseball led the country on civil rights and integration.

His extraordinary statistical accomplishments speak for themselves, but the grace, joy, energy and intellect with which he played the game allowed him to separate himself from other great players of his, or any, era.

Mays’ death is not only a loss for baseball, but for all of America. Willie Mays is a reminder of what America can produce and how there is always hope that the country can transcend its ugly racial history and embrace a graceful, talented and proud African American man as a uniquely important national hero.

![]()

Lincoln Mitchell is an Adjunct Research Scholar in the Arnold A. Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies and Adjunct Associate Professor of Political Science in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University.

Leave a Reply