By Shannon Toll

Each year on the fourth Thursday of November, when many people start to take stock of the marathon day of cooking ahead, Indigenous people from diverse tribes and nations gather at sunrise in San Francisco Bay.

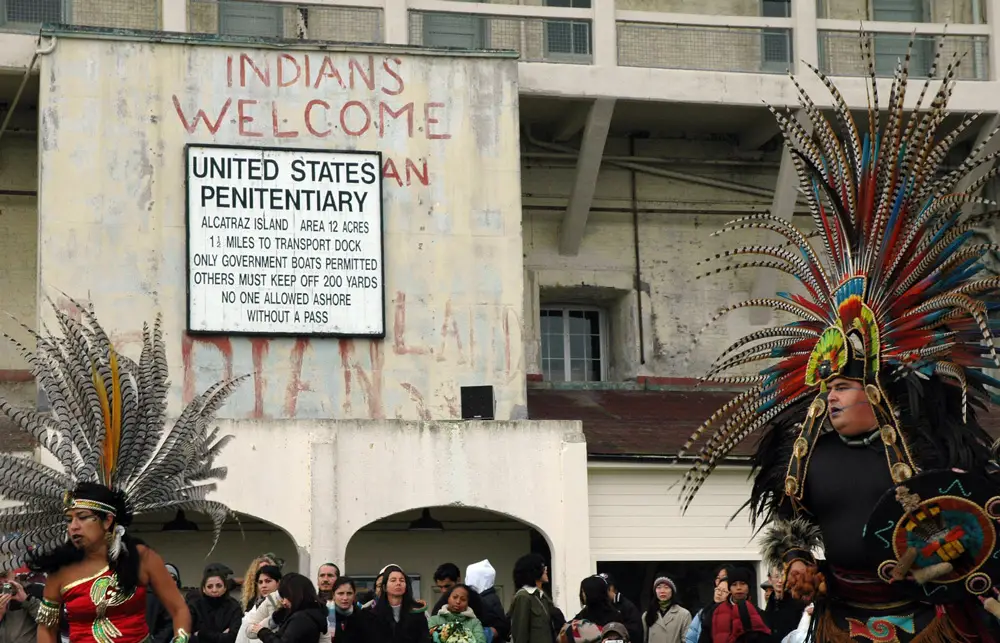

Their gathering is meant to mark a different occasion – the Indigenous People’s Thanksgiving Sunrise Ceremony, an annual celebration that spotlights 500 years of Native resistance to colonialism in what was dubbed the “New World.” Held on the traditional lands of the Ohlone people, the gathering is a call for remembrance and for future action for Indigenous people and their allies.

As a scholar of Indigenous literary and cultural studies, I introduce my students to the long and enduring history of Indigenous peoples’ pushback against settler violence. The origins of this sunrise event are a particularly compelling example that stem from a pivotal moment of Indigenous activism: the Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island, a 19-month-long takeover that began in 1969.

Reclaiming of Alcatraz Island

On Nov. 20, 1969, led by Indigenous organizers Richard Oakes (Mohawk) and LaNada War Jack (Shoshone Bannock), roughly 100 activists who called themselves “Indians of All Tribes,” or IAT, traveled by charter boat across San Francisco Bay to reclaim the island for Native peoples. Multiple groups had done smaller demonstrations on Alcatraz in previous years, but this group planned to stay, and it maintained its presence there until June 1971.

Before this occupation, Alcatraz Island had served as a military prison and then a federal penitentiary. U.S. Prison Alcatraz was decommissioned in 1963 because of the high cost of its upkeep, and it was essentially left abandoned. In November 1969, after a fire destroyed the American Indian Center in San Francisco, local Indigenous activists were looking for a new place where urban Natives could gather and access resources, such as legal assistance and educational opportunities, and Alcatraz Island fit the bill.

Citing a federal law that stated that “unused or retired federal lands will be returned to Native American tribes,” Oakes’ group settled in to live on “The Rock.” They elected a council and established a school, a medical center and other necessary infrastructure. They even had a pirate radio show called “Radio Free Alcatraz,” hosted by Santee Dakota poet John Trudell.

The IAT did offer – albeit satirically – to purchase the island back, proposing in the 1969 proclamation “twenty-four dollars (US$24) in glass beads and red cloth, a precedent set by the white man’s purchase of a similar island about 300 years ago,” referring to the purchase of Manhattan Island by the Dutch in 1626.

On behalf of IAT, Oakes sent the following message to the regional office San Francisco office of the Department of the Interior shortly after they arrived:

“The choice now lies with the leaders of the American government – to use violence upon us as before to remove us from our Great Spirit’s land, or to institute a real change in its dealing with the American Indian … We and all other oppressed peoples would welcome spectacle of proof before the world of your title by genocide. Nevertheless, we seek peace.”

After 19 months, the occupation ultimately succumbed to internal and external pressures. Oakes left the island after a family tragedy, and many members of the original group returned to school, leaving a gap in leadership. Moreover, the government cut off water and electricity to the island, and a mysterious fire destroyed several buildings, with the Indigenous occupiers and government officials pointing the blame at one another.

By June 1971, President Richard Nixon was ready to intervene and ordered federal agents to remove the few remaining occupiers. The occupation was over, but it helped spark an Indigenous political revitalization that continues today. It also pushed Nixon to put an official end to the “termination era,” a legislative effort geared toward ending the federal government’s responsibility to Native nations, as articulated in treaties and formal agreements.

Solidarity at sunrise

In 1975, “Unthanksgiving Day” was established to both mark the occupation and advocate for Indigenous self-determination. For many participants, Unthanksgiving Day was also a reiteration of the original declaration released by IAT, which called on the U.S. to acknowledge the impacts of 500 years of genocide against Indigenous people.

These days, the event is conducted by the International Indian Treaty Council and is largely referred to as the Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering.

Participants meet on Pier 33 in San Francisco before dawn and board boats to Alcatraz Island, bringing Native peoples and allies together in the place that symbolizes a key moment in the long history of Indigenous resistance.

At dawn, in the courtyard of what was once a federal penitentiary, sunrise ceremonies are conducted to “give thanks for our lives, for the beatings of our heart,” said Andrea Carmen, a member of Yaqui Nation and executive director of the International Indian Treaty Council, at the 2018 gathering.

Songs and dances from various tribal nations are performed in prayer and as acts of collective solidarity. At the same gathering, Lakota Harden, who is a Minnecoujou/ Yankton Lakota and HoChunk community leader and organizer, emphasized that “those voices and the medicine in those songs are centuries old and our ancestors come and they appreciate being acknowledged when the sun comes up.” Through the sharing of song and dance, they enact culturally resonant resistance against the erasure of Native peoples from these lands.

The Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering also gives people the chance to bring greater community awareness to current struggles facing Indigenous people across the globe. These include the intensifying impacts of climate change, the widespread violence against Native women, children and two-spirit individuals, and ongoing threats to the integrity of their ancestral homelands.

Resistance beyond The Rock

Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering lands near the end of Native American Heritage Month, which is dedicated to celebrating the vast and diverse Indigenous nations and tribes that exist in the United States. Professor Jamie Folsom, who is Choctaw, describes this month as a chance to “present who we are today … (and) to present our issues in our own voices and to tell our own stories.”

The people who will meet on Pier 33 on the fourth Thursday of November continue this story of Indigenous political action on the Rock and, by extension, in North America. The more than 50-year history of this gathering is a testament to the endurance of the original message from Oakes and Indians of All Tribes. It is also part of a larger network of resistance movements being led by Native peoples, particularly young people.

As Harden says, the next generation is asking for change. “They’re standing up and saying we’ve had enough. And our future generations will make sure that things change.”

![]()

Shannon Toll is Associate Professor of Indigenous Literatures at the University of Dayton.

Leave a Reply