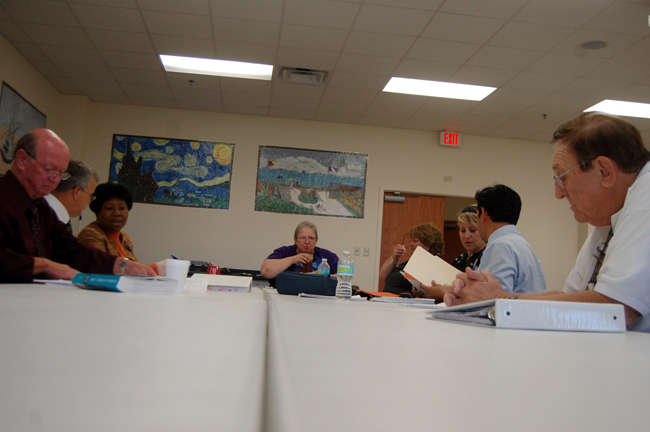

Flagler County school district management held its first negotiating session with its two employee unions Wednesday to find agreement on budget cuts of more than $3.5 million—or close to 4 percent of the district’s general-fund budget—before the new fiscal year begins on July 1. The two sessions were cordial but unproductive. The two sides agreed to meet again on April 15 for a budget workshop, where the unions want to hear the district’s latest financial figures. They’ll meet again three days later to negotiate.

Those negotiations may seem arcane, and certainly sounded it for the most part to ears unfamiliar with the grind of bargaining sessions. But the negotiations’ outcome will affect most of the district’s 13,000 students and their parents, as well as most of the district’s 1,700 employees. It will also have ramifications on the local economy. The district is the county’s largest employer by far. Substantial layoffs or reduced work days and work hours there will ripple across the local economy. Layoffs and reduced schedules are at the heart of the negotiations.

Several obstacles got in the way of discussing either side’s proposals on Wednesday. The unions and the district disagreed over the parameters of the negotiating sessions. The district’s chief negotiator, Jerry Copland, intended the sessions to be “impact negotiations,” which narrowly define the scope of matters to be discussed to financial issues that affect most employees—namely, specific ways to cut dollars out of the budget. The unions expected the negotiations to include discussions of contract language, which they are entitled to do periodically.

There was also a tactical dimension to the union’s objection: an “impact negotiation” ultimately gives the school board the final say, no matter what’s decided in negotiations. Will Vargas, the union’s service unit director, and Katie Hansen, president of the Flagler County Educators Association (the teachers’ union) said delving immediately into impact negotiations made it seem as if the board had already made up its mind, and was only looking for union input after deciding what it will do. Talks about the contract language diminish the unilateral approach.

Another disagreement was the set of numbers each side was submitting. Both sides’ numbers looked more fluid than they should have by then: the district submitted a one-sheet list of proposed cuts to the union representing the service employees at the first meeting. That list was presumably the one the school board approved, with areas the board was willing to cut highlighted in green. But the list the district submitted to the teachers union in the later meeting was different.

On it, an additional $250,000 savings that had not been part of the school board’s approved list suddenly appeared. Mike Judd, one of the members of the district’s negotiating team and a senior director for facilities, explained that the $250,000 saving could be generated by designating one elementary school as an “overflow” school should the student population exceed class-size rules in some schools. Instead of spreading out additional teachers in those schools, the overflow would be concentrated in a single school, presumably saving money. No one disputed the logic. But the appearance of the figure looked suspect, and hurt the credibility of the district’s figures.

The same thing happened with the unions’ figures. Hansen has been critical of the school board for protecting pet projects while balancing its books on the back of teachers, some 40 of whom might lose their job according to the school board’s plan. Hansen produced a list showing more than $5 million in savings without laying off teachers. But that list immediately drew criticism in and out of the negotiating room as some figures jumped out as unrealistic, namely a $4 million savings from waiting next year’s purchase of new science textbook. The actual cost of those textbooks is closer to $600,000. The district disputed several other figures on the list. The updated list Hansen provided Wednesday afternoon had lowered projected savings to $2.4 million, “not including unknown amounts.”

There was a distinct point of agreement. But it was the sort of agreement that only lent credence to the unions’ claim that the district was looking to negotiate in the absence of crucial facts that should be factored in. The governor and the Legislature are likely to require all public employees to contribute 3 percent of their pay to the Florida Retirement System. That 3 percent will diminish by an equal amount the sum the state will be required to put in. Initial proposals were to free that money to be used in reducing the state’s projected $4 billion deficit. But educators say the money may be shifted back to education. Should that be the case, school employees say the state would shift an equivalent amount available to education funding, which, locally, would diminish the emergency—and lessen the need to look at personnel cuts.

Each negotiating session lasted about two hours. The discussions were only occasionally tense, when time lines and the detail of what was, and wasn’t, said by one side to the other in previous communications was in dispute. Copland did most of the talking for the district, with Senior Director Mike Judd and Human Resources Director Harriett Holiday chiming when Copland needed details he didn’t have. Copland himself was as courteous as he was hard-nosed, rarely hiding his skepticism when he disagreed with the unions.

“We are going to be down about $7.7 million,” Copland told the service employees’ union in words he’d repeat in the subsequent meeting. “In order to get to that we need to make several adjustments in an attempt not only to maintain the integrity of our workforce in the county but in every way possible trying to minimize the impact upon them, and at the same time trying to save some money.”

The other side of the table was led alternately by Vargas and Tammy Whitacker, the union’s regional specialist, during the meeting with the union representing non-instructional employees, with Becky Harper, the union president, speaking on occasion. During the negotiations with the teachers union, Hansen led her team, with Vargas and Whitacker in supporting roles. (Several other teachers sat alongside the union’s bargaining team, including David Morris, a teacher at Bunnell Elementary, Pam Batten, a teacher at Wadsworth Elementary, Jo Ann Nahirny, a teacher at Matanzas High School, and Jessica Clark, a teacher at Rymfire Elementary.”)

“Enough is enough,” Whitacker told Copland. “We cannot continue to do this and bleed our school and make our employees bleed to death” to ensure that students get their education. In the subsequent meeting, Whitacker was more precise: “We’re not going to agree” to the cuts being proposed by the school district. “We need to come up with an option that doesn’t balance the budget on the back of the teachers and still get us to where we need to be.”

“That’s why we call it negotiations,” Copland said, before pointing out that when that much money needs to be cut, and when 85 to 87 percent of the budget is made up of salaries and benefits, it’s almost impossible to make deep cuts without affecting personnel. “We ain’t going to get through this without each other and this is probably the worst financial crisis I’ve seen in the state of Florida in at least the last 50 years,” Copland said. “And it’s going to take us both.”

There was no disagreement on that point, though Hansen reiterated a point she’d made to board members earlier in the week: No program should be sacred, particularly “pet projects.” There has to be “give on both sides,” she said.

Maja says

This is getting ridiculous. I understand, the economy, the economy. I have come to understand that the FCAT costs about 52 million dollars. Why waste money on something so useless? It is completely useless. It helps not one soul. The schools need to raise their standards, not bring them down to one child who is just dragged from one grade to the next. It seems that parents aren’t too involved in their kids life, they simply don’t care. Any other country would raise their voices and say it’s an outrage. Here, they sit quiet. What kind of world do we live in? Where our children are learning the same thing over and over? Take a look at some successful education areas. Such a Finland.

lawabidingcitizen says

If teachers want more in their pockets, get rid of the unions and put their take back in their own pockets.

palmcoaster says

From which corporate giant VIP position have you retired lawabiding? I know some from Mobil, Chevron and Shell and other corporations, enjoying their lavishly lifestyles among us here in Flagler.