Skirting what would have been an unprecedented vote by one autonomous government against another, the Flagler County Commission this evening, rather than reject the Flagler County School Board’s request to double its development impact fees, opted to further delay a decision, as it did in September. The commission, uneasy–if not mistrustful–of the district’s numbers, will again seek a compromise with the school board over the next 60 days, though the two sides have essentially been at an impasse for the past several weeks. The district has opposed revising the impact fee increase it insists it needs.

The commission voted 4-1 to afford another 60-day window, with Commissioner Dave Sullivan in dissent. He was ready to reject the district’s request, since it isn’t in the commission’s purview to offer up a schedule of its own: that number may only be produced by the school board. Commissioners warned the 60-day delay will be the last. At that point, if the school board doesn’t have alternate figures, the commission may either reject the request or accept it whole. If it rejects it, the matter goes to mediation. But mediation is non-binding. Ultimately, the fate of the fee schedule either rests in the commission’s hands or would be litigated. Home builders have already threatened litigation if the district’s current figures go through.

Impact fees are the one-time levies on new residential development intended to defray the cost of new schools. Cities, counties and school boards impose them to help build schools, fire houses, police stations, parks, roads and utilities. Fees can’t be raised or imposed arbitrarily. They must abide by a methodical, rational approach. Tonight’s commission workshop was part of that approach.

The district projects needing an additional $65 million middle or high school in four years, and a $17 million addition at Matanzas High in two years. It argues that it cannot finance those schools without the doubling of its impact fees.

The district hasn’t increased its impact fees since 2005. The district’s student population had stalled for a decade, until 2018. The stall is over. Growth has resumed at a brisk pace. The current fee structure is generating $6.4 million a year, based on 1,800 new homes being built each year, with $2.5 million of that absorbed by debt service for two schools built years ago.

What’s left, even if bonded, is not enough to build what’s needed ahead, the district argues. “Yes, we can deal with overcrowding,” Superintendent Cathy Mittelstadt said, anticipating the commission’s rejection. “It’s just going to be different decisions our board will have to make that will impact the level of service we have in our community, our parents right now. I’m trying to preserve the quality of what we provide today, that we have right now.” She said the fees were calculated in proportion to the needs ahead.

The school board has already unanimously approved increasing its fees. Normally the step before the county commission would have been a mere ratification. No longer: a change in law this year limits how much and how often a government may increase its impact fees, absent proof of “extraordinary circumstances.” The district is claiming extraordinary circumstances–and needs the County Commission to endorse that claim.

That’s what the commission refused to do tonight, at least for the next 60 days.

“I really don’t understand why the builders are against this because it is a pass-through,” Commissioner Greg Hnasen said. “But I do understand their stand that these numbers are inaccurate. So I think that’s the issue. Do you believe or not believe that we’re going to have student growth, and I don’t have a crystal ball. So maybe those numbers need to be looked at a little closer and wrung out a little better.”

Commissioner Andy Dance, a former school board member, was a key voice because of his former role–and his naturally friendly disposition toad his former colleagues. But even he had issues with the lack of “collaborative” efforts on the district’s part, saying that could be improved. But he did not question the district’s numbers. “This process is a series of assumptions and progressions,” he said. He also pointed out an important contradiction: when the County Commission itself doubled its impact fees (at lower numbers), none of his colleagues worried about “affordability,” but here they were, “nitpicking” the school board over affordability.

Dance also dismissed a concerne by fellow-Commissioner Joe Mullins, who’d questioned why the district hadn’t rezoned for so many years. “Rezoning is hugely disruptive,” Dance said, and remains a last resort to avoid such disruptions. That’s why the district is rezoning only now, and gradually so.

The school board earlier this year approved increasing the impact fee for a single family home from $3,600 to $7,175, an increase of $3,575. The fee on apartment units was to increase from $931 to $1,774, an increase of $843. And the fee on mobile homes was to almost quintuple, from $1,066 to $5,279, an increase of $4,213. Overwhelmingly–by a factor of 13–students live in single-family homes.

The County Commission initially revealed its opposition to the district’s plan at a mid-September workshop, stunning school officials, but also giving them a chance to spend the following few weeks meeting with county officials to make their case. Those meetings took place. They did not change commissioners’ minds.

Today’s workshop–required by law in the impact fee process–was the district’s last chance to press its case. It not only faced opposition from commissioners, but from builders and developers, who also spoke. In contrast with the September meeting, when no parents with children in the schools spoke, this time a few did, one of them describing schools as “busting at the seams,” as “stressed” and best by innumerable tensions. But even a parent pressing for the increase saw value in tabling the matter, if only to give the school board more time to make its case.

“I’m not saying that what the school board is saying is incorrect,” Michael Chiumento, the Palm Coast attorney who chiefly represents developers, told the commission. He has opposed the district’s plan. “I do believe that there’s another side of the story that we have to evaluate. A lot of this is based on inferences based on assumptions that we have to get right this first time, because maybe they can’t do an impact fee study for another four years.”

He argued for a pause, not a rejection, raising the prospect of the alternative: litigation. “I don’t think any of us need to be in that and I don’t think our side of the table wants to be in there,” he said.

Toby Tobin, a Realtor, pointed out significant inaccuracies in some of the district’s numbers, such as the misleading figure cited for the typical impact fee on a home in St. Johns County, or the number of permits pulled for new homes on existing lots in Palm Coast.

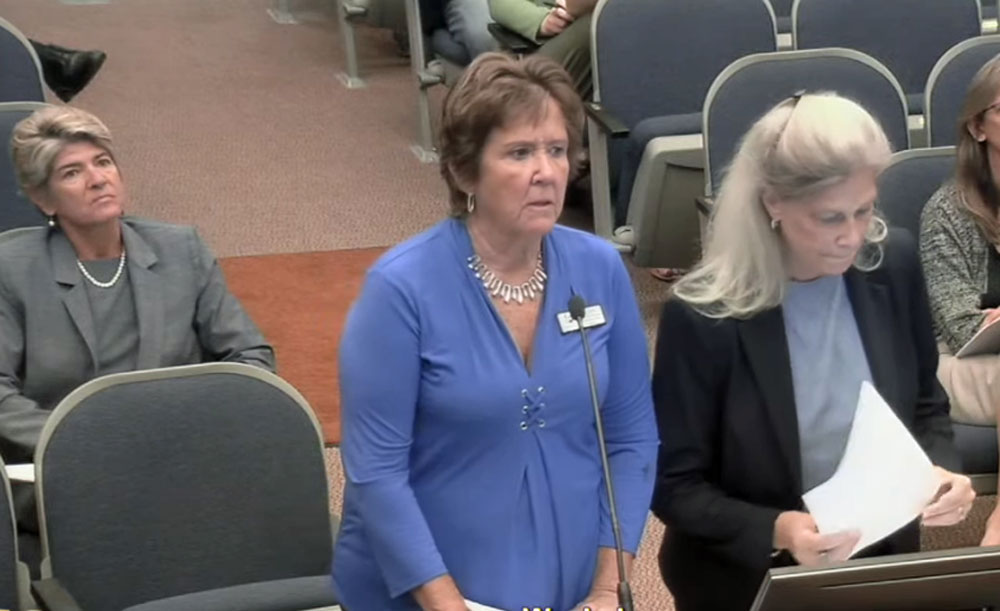

The district’s Patty Bott, who took the lead on impact fees, and Kristy Gavin, the district’s attorney, presented the district’s numbers to the commission in an attempt to address objections raised at the September meeting–objections raised especially by the Flagler County Home Builders Association.

Like supreme court judges skeptical of one side over another during oral arguments, four of the five county commissioners almost immediately began challenging the presentation by Gavin and Bott. The exception was Commissioner Andy Dance, a former school board member still familiar with the district’s demographics. The commissioners raised the same questions they’d raised in September–doubting the district’s projections, questioning the demographic make-up of the population increase, doubting the need for an up-front doubling. The exchanges verged on the testy, but never crossed the line.

By the half hour mark, the lawyer in Gavin was more clearly willing to push back on the commissioners’ challenges, as when Sullivan asserted that developers add the cost of impact fees to the sales price of a home at the point of sale.

“That is the choice of the developer on whether or not they want to pass on that cost to the homebuyer,” Gavin said.

“I don’t see them doing that,” Commissioner Joe Mullins said.

“I wholly agree with you, but it is their option,” Gavin said.

Commissioners raised questions about the “reservations” for student stations, or spots, in schools that the district receives from developers. A reservation is essentially a projected student enrollment, pending the development;s completion. Those reservations have exploded. For example, the district received applications for “reservations” from developers for the equivalent of 74 students in 2018, 102 in 2029, 459 in 2020.

Through October 1, the district has received applications equivalent to an additional 481 students, about half a school. Despite the numbers, the commissioners were skeptical about the numbers, first because the applications are not a reflection of actual students but expected students. Second, because the growth trend in Flagler has been driven largely–but not entirely–by older residents. Mullins raised the latter objection.

“With all due respect, sir, in our county, two out of every 10 homes have a child come out of them,” Bott said. None of the developer applications include those developments that are restricted to residents 55 and over.

“I want to remind the county that we have also seen that there are young families who have moved in with their parents,” Gavin said. “and we are picking up students from homes where an elderly population would be deemed to live. Yet, they actually are with students being picked up.”

Bott and Gavin pulled whatever stops they could to make their case, systematically laying out data, legal wording, analysis and projections. But there came a point where it seemed as if no matter how much data the district’s officials were presenting, the commissioners’ questions were grounded in preconceived opposition that made the exchange sound as if the two sides were talking about two different things.

Commissioners had been especially doubtful of the way the district was projecting student-population increases in coming years. The district devised a more accurate way to project those numbers by working with the property appraiser and defining precisely where and how many students lived, based on types of households. It was not a guess. It resulted in an accurate portrait of how many students live in single family homes, how many in mobile homes, and how many in apartments–and how many would be added based on the equivalent proportionate increases in those categories. But even that explanation from Bott seemed not to gain much traction.

Each of the five school board members addressed the commission in turn. They asked for their numbers to be believed, and for cooperation. “I hope we can get beyond the differences that we might see,” School Board member Colleen Conklin said.

School Board member Jill Woolbright said the school board did its due diligence for almost a year. “Schools are expensive,” she said. “Schools are really expensive. And our schools have to meet a lot of building codes that other buildings don’t have to meet because we have to be built as Cat 5 hurricane shelters for our whole community.” She also cautioned that the district would halt granting development approval if it runs out of capacity. Those approval are required by “concurrency” laws to ensure that development doesn’t run local governments’ abilities to tend to all the infrastructural and educational needs those developments would require.

In an astounding retort, O’Brien told Woolbright that the county could simply change its comprehensive plan to get around that–a statement that reflected a more simplistic than responsible understanding of concurrency.

“I would certainly hope no one in this room would threaten to attack or hurt this economy. That would be insane,” Mullins said. “That would be insanity that I’m going to hurt or stop or destroy the economy because I didn’t get my way.” As is often the case Mullins was mischaracterizing the issue: the district is legally required to sign off–or not sign off–on new developments, based on its school capacities. It would be the county, not getting its way, that would be jeopardizing the economy by opposing the district’s plan.

Tonight’s meeting was mostly conducted in a workshop setting. The two-hour meeting was followed by a brief meeting, where commissioners took the vote, since they could not vote in a workshop. They adjourned at 8:40 p.m.

Dave says

Increase them while we have all the suckers moving in here might as well get rich!

Land of no turn signals says says

What’s the problem? when the county wants to raise fee’s [ taxes] they do it hardly without a peep.Hold the extra impact fee’s for the the future residents are going to need it.Apartment buildings hardly pay there fair share. Double triple it’s time to pay up to Paulie.

Doreen says

WOW! Could Don O Brien really be that arrogant. What an immature response! You can see it now, he has made it apparent … if he doesn’t get what he wants, he’ll get the rules changed. Sounds familiar.

Jimmy says

The school board and administration can’t be trusted. They contradicted themselves in the presentation several times and basically lectured the BOCC. Shocker, it didn’t go over well! This is a money grab, plan and simple. And this is just the beginning…wait until they ask for sales tax renewal. And who pays for the upkeep of these supposed new schools? You do. Wake up y’all…it’s not all about new homes paying.

Jane Gentile-Youd says

Boy oh boy.. Am saving my comments to be made in person to the county Commissioners on the scheduled date. My homework will be delivered in my 3 minutes allowed. The commissioners represent the VOTERS.. something they ..with exception like Andy..do not comprehend or don’t give a rat’s behind about WHO pays their salary! CHUTZPA at its best..