By Stephen P. Leatherman

An unwelcome visitor is headed for Florida and the Caribbean: huge floating mats of sargassum, or free-floating brown seaweed. Nearly every year since 2011, sargassum has inundated Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and Florida coastlines in warm months, peaking in June and July. This brown tide rots on the beach, driving away tourists, harming local fishing industries and requiring costly cleanups.

According to scientists who monitor the formation of sargassum in the Atlantic Ocean, 2023 could produce the largest bloom ever recorded. That’s bad news for destinations like Miami and Fort Lauderdale that will struggle to clean their shorelines. In 2022, Miami-Dade County spent US$6 million to clear sargassum from just four popular beaches.

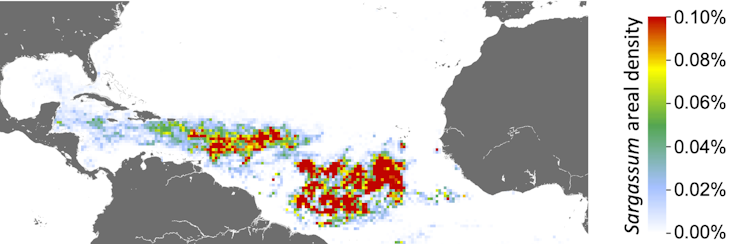

USF/NOAA, CC BY-ND

Sargassum isn’t new on South Florida beaches, but its rapid increase over the past decade indicates that some new factor – likely related to human actions – is affecting when and how it forms.

In my work as a coastal scientist, I’ve watched these invasions become the new normal, choking beaches and turning clear blue waters golden brown. Along with other researchers, I’m trying to understand why sargassum has proliferated into this new sprawling bloom, how to deal with such massive amounts of it, and how affected countries can predict the severity of the next influx.

A biological hot spot at sea

Sargassum grows in the calm, clear waters of the Sargasso Sea – a 2 million-square-nautical-mile (5.2 million-square-kilometer) haven of biodiversity that lies east of Bermuda in the Atlantic Ocean. Rather than beaches, it’s bounded by rotating ocean currents that form the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre.

Jack/Wikipedia

In the open ocean, islands of sargassum create a rich ecosystem that ocean explorer Sylvia Earle calls “a golden floating rainforest.” Suspended by round “berries” filled with gas, the seaweed offers food, sanctuary and breeding grounds for crabs, shrimp, whales, migratory birds and some 120 species of fish. Mats of it form the sole spawning grounds for European and American eels and habitat for some 43 other threatened or endangered species.

Sargassum also shelters sea turtle hatchlings and juvenile fish during their early life in the open ocean. Ten endemic species live nowhere else on Earth. The Sargasso is a valuable commercial fishery worth about $100 million per year.

But in recent years, large quantities of sargassum have drifted west, forming what researchers call the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. As of late March 2023, the sargassum belt was about 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers) long and 300 miles (500 miles) wide

The belt is actually a collection of island-like masses that can stretch for miles. It doesn’t uniformly cover beaches when it washes up: Some areas can be relatively clear or only mildly affected. But the overall mass this year is overwhelming.

What’s fertilizing huge blooms?

What can plausibly explain the sudden increase in this floating seaweed since 2011 – the first time that large aggregations of sargassum were detected from space? While climate change is warming ocean waters, and sargassum grows faster in warmer water, I believe it’s more plausible that the cause is a drastic increase in agricultural activity in the Brazilian Amazon.

Scientists have shown that huge brown tides that were observed in the Gulf of Mexico in 2005 and 2011 were linked to nutrients carried down the Mississippi River. Now, intensive cattle ranching and soybean farming in the Amazon basin are sending rising levels of nitrogen and phosphorus into the Atlantic Ocean via the Amazon and Orinoco rivers. These nutrients are key ingredients in fertilizer, and also are present in animal manure.

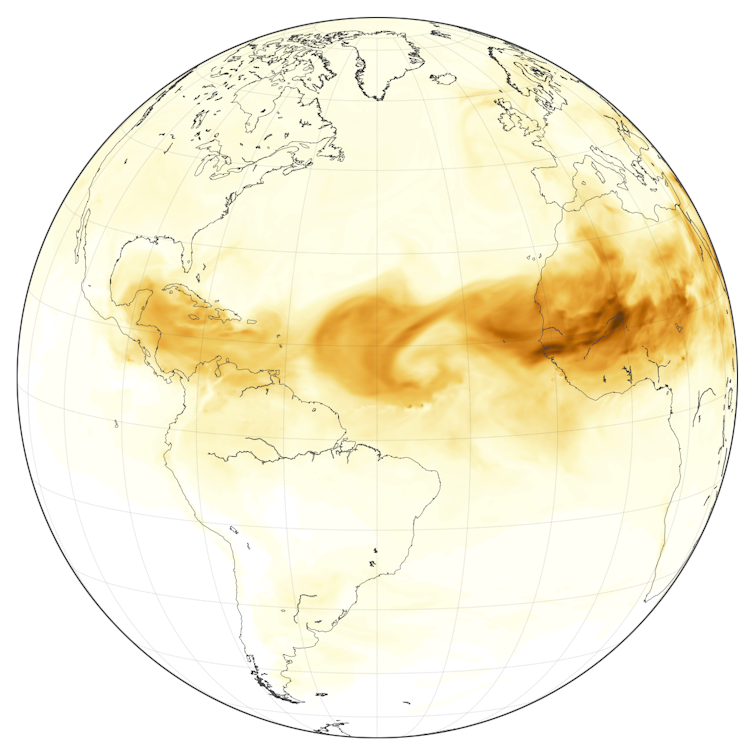

Another major source of nutrients is dust clouds from the Sahara, which can stretch for thousands of miles across the Atlantic Ocean, carried by trade winds. These clouds contain iron, nitrogen and phosphorus from dust storms in Saharan Africa and biomass burning in central and southern Africa. As they blow across the Atlantic, they help fertilize seaweed.

NASA Earth Observatory

A threat to sea life

Along with its devastating effects on recreational beaches in the Caribbean and South Florida, sargassum has important but less visible ecological impacts near the coast. Large floating mats of sargassum block sunlight, which is essential for the survival of underwater grasses. These grasses stabilize the seafloor and provide food and shelter for many species of fish and invertebrates and for Florida’s endangered manatees.

Coral reefs also require sunlight and clean water to survive. Reefs in Florida and the Caribbean are under many other stresses, including ocean warming and coral bleaching, so they are already highly vulnerable.

Thick masses of sargassum on beaches can make it difficult or impossible for endangered sea turtles to dig nests and lay eggs on beaches. Spring and summer, when sargassum accumulates, are prime sea turtle nesting seasons.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Taming the sargassum monster

Researchers across the Caribbean are working to find productive uses for these enormous quantities of organic material that float ashore. In South Florida, communities mainly use the seaweed as mulch, but this requires thoroughly washing it to remove the salt, either naturally via rainfall or by spraying it with fresh water. Recycling sargassum into fertilizer for use on crops is problematic because it often contains toxic heavy metals such as arsenic and cadmium.

Sargassum has become a recurring seaweed monster, but humanity is the real villain. Until nations find ways to reduce large-scale nutrient pollution, I expect that huge sargassum blooms will be a recurring presence in Florida and the Caribbean.

![]()

Stephen P. Leatherman is Professor of Coastal Science at Florida International University. This is an update of an article published Aug. 2, 2021.

G A says

I would be very interested to see what if anything DeSantis does. Since it has nothing to do with guns or abortion probably nothing

Jimbo99 says

Saharan Sand Dust, Continent of origin, Africa. What are African nations/leaders doing about it ? If you look at the dust belt, FL isn’t in that path. But the nutrients that the sand dust has created the seaweed mass. Me, I’m for the seaweed washing ashore and fortifying the impact zone of sand. It’s a free beach nourishment of fertilizer & the sand will accumulate over it. Not the most pleasant smelling beach, but certainly a preferably better alternative to the garbage the locals & tourists pollute it with ?

JOE D says

Covid….hurricanes…..now seaweed invasion…..what’s NEXT…!?

Opps, did I say that OUT LOUD? The Caribbean and Miami have been scooping it up off the beaches ($$$), because the rotting seaweed releases sulfur dioxide gas (smell of rotten eggs)… not exactly a tourist draw….Just what Florida’s beaches need now….at least what’s LEFT of them.

Sea Witch says

It might make Hurricane season a little less severe this year…… Then again, it might make it worse.

Do Insurance companies cover damage from tons of flying seaweed landing on your roof and crushing it ?

Somebody ask JAKE from State Farm

Jimbo99 says

I doubt you’ll find enough airborne seaweed to damage a home’s roof. Now if the ocean surge floods high enough to wash the seaweed 8 plus feet & onto the roof, chances are the surf action will wash away your dwelling walls & roof long before the seaweed does.

Jimbo99 says

Perhaps a plus for the floating seaweed is that it ultimately washes ashore & fortifies the beach from erosion ? Maybe it’s bad for tourism because it stinks or whatever else wouldn’t be attractive to tourists, but it’s also similar to the root system of plants for the dunes and it’s distributed as the tides & waves wash it ashore. Consider it’s nature’s free beach enrichment solution that is a totally natural solution. Recreational & commercial watercraft won’t like the seaweed, but who cares what they like, they won’t be polluting the ocean with their fossil fuel/oil ?

Donald J Trump says

Lived and fished in South Florida for 40 years, best thing to fish under for Mihai Mihai ever. Maybe the wind and current will push it north and smoother Mira Logo, then I can file insurance claims and tax deductions.

Nothing better to do says

Two words, Global Warming!

Dave says

Should be fun. But yes, fishing in it or under it well before it gets to the beaches is a blast., Trigger fish abound