“Humming along” is how Flagler County Property Appraiser Jay Gardner describes the year’s property values: powered by nearly $1 billion in new construction alone, $631 million of it in Palm Coast, taxable property values in Flagler County rose around 12 percent this year, and 13 percent in Palm Coast, about the same as last year.

The numbers are strong in most cities and the county. They reflect where values stood as of Jan. 1. They’re not as strong as last year, if by very small margins in Palm Coast and the County but by much larger margins in Bunnell and Flagler Beach, while early numbers for the five months since the new year point to a sharper slow-down that, if sustained, will worry local officials and compound a slow-down in home sales and decreasing home prices.

The estimates being finalized this week play a central role in local governments’ budgeting decisions as administrations calculate how much more (or less) money they may have to spend next year, and as elected officials consider whether to raise taxes or keep them in check.

More than half of the taxable value increase in Palm Coast is due to new construction. That will generate roughly $2.7 million in new revenue at today’s tax rate, which will not be considered a tax increase because it’s on new construction. The city could see some new revenue from existing properties that have seen their values increase (though not as much), even if the city did not increase its property tax rate.

That revenue from existing property owners–as opposed to new construction–would be wiped out if the city council does this year what it did last year: adopt a rolled back tax rate, meaning a rate that will generate the same amount of money as it did last year. At least one member of the council wants to do that. Others are less interested in a repeat of last year as the city administration has been making the case that it has tightened its belt to the limit, with looming, necessary but unfunded projects ahead, particularly in public works, including road repair, and potential, additional commitments to fire and police services.

The county would benefit from an even larger windfall from new construction: $7.5 million, with some additional revenue from existing property owners if the tax rate were left flat. The County Commission has adopted small, symbolic reductions in the property tax rate over the last few years, but has resisted going back to the rolled back rate.

Flagler Beach had a much more modest increase of 3.5 percent, only $40 million of it powered by new construction. But that may be the calm before dozers roll in as the city prepares to annex Veranda Bay, a large development of high end homes along John Anderson Highway. Last year, Flagler Beach saw its taxable values increase by 9 percent.

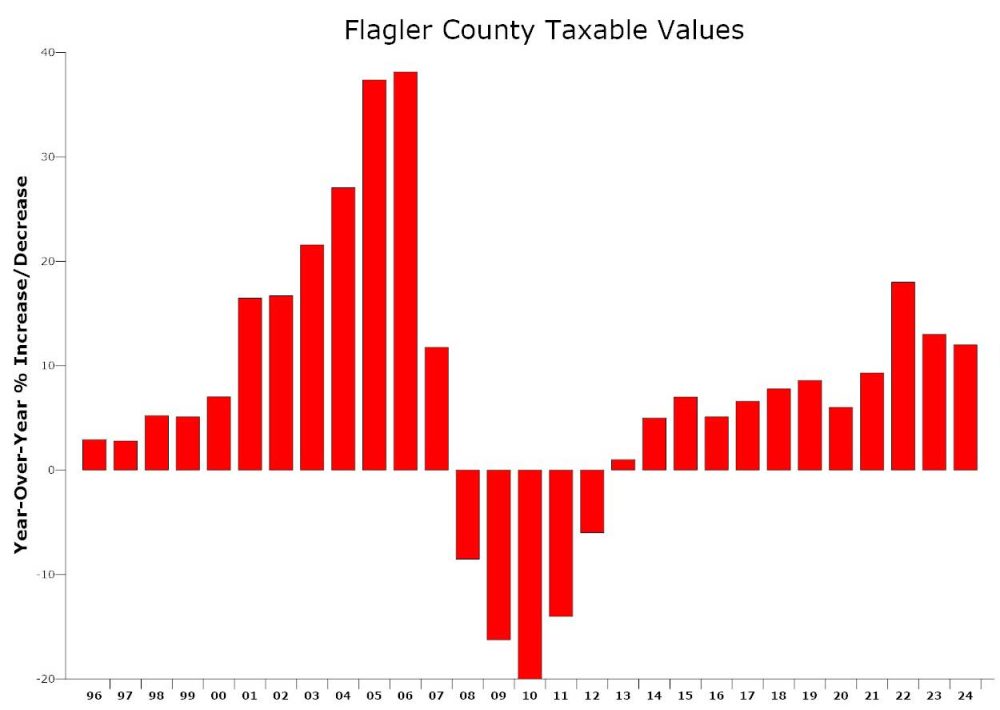

As they set their tax rates, elected officials will likely look not just at this year’s taxable value numbers, which are still robust, but at the trend since the peak of 2021, when values increased year-over-year by 18 percent, the most since the housing boom of two decades ago. In that sense, Bunnell and Flagler Beach may be the sentinels of what’s ahead.

Bunnell is a surprising laggard in taxable values, at just 6.3 percent, less than half last year’s 13.3 percent increase, when homes were rising quickly at Grand Reserve, the big development to the northeast of the city. There’s been less construction over the past year, with new construction accounting for just $19 million of the city’s new values, and even less construction in the first five months of this year. Marineland, a city of seven residents, saw no new construction, though Marineland’s mayor says the city is exploring acquiring land to build housing for its corps of seasonal residents who work at the University of Florida’s Whitney Lab and at the dolphin attraction. That’s in the future. Existing taxable values increased 3.4 percent in town.

When property values rise, the same tax rate can generate more revenue for governments–but not at all uniformly. That same tax rate will take disproportionately more money out of commercial properties, rental properties and non-homesteaded properties than it will out of homesteaded properties, which benefit from several layers of protection that blunt tax increases.

For example: assume you have a $300,000, and the tax rate is $4.257 per $1,000 in taxable value, as it currently is in Palm Coast. If your house is not homesteaded, you’re paying $1,247 in property taxes to Palm Coast. (You’re obviously paying more to the county, the school board and other taxing authorities.) If it’s got a $50,000 homestead exemption, you’re paying $1,064. If your taxable value goes up 10 percent, to $330,000, you’ll be paying $1,404, or $157 more. But if you’re homesteaded, the so-called Save Our Homes constitutional amendment limits any taxable value increase to 3 percent (or to the previous year’s inflation rate, whichever is less. In this case, it’ll be 3 percent.) So instead of paying that additional $157, you’ll pay just $38 more.

In reality, the majority of homesteaded properties have seen their overall taxes stay flat or decline over the past decade and a half. When accounting for inflation, those properties have been paying significantly less in constant dollars today compared to, say, 10 years ago.

It’s the reverse for businesses, rental properties and other non-homesteaded properties. Take the Publix shopping center in Town Center. Ten years ago it had a taxable value of $4.1 million. It paid Palm Coast $17,700 in taxes, out of a total of $97,000. Its taxable property value has increased 60 percent in 10 years. Last year, it had a taxable value of $6.8 million. It paid Palm Coast $28,500, or 61 percent more than it did 10 years ago, out of a total bill of $138,000. (Commercial properties benefit from a 10 percent cap on annual increases in their taxable value.)

Those differences are often lost in politicians’ discussions about who needs a tax break and who doesn’t. It isn’t the people on fixed incomes, living in properties with multiple homestead exemptions (seniors get the benefit of an additional $50,000 exemption, if their income is low, and those seniors who have lived in their home 25 years or more get yet another $50,000 exemption). Even Gardner, the property appraiser, finds the homestead system skewed.

“Where does it stop? That’s what I say to it,” Gardner said. “The senior thing, you’re not more entitled because you’ve lived here longer. You’re entitled because you’re a low income senior. Fine. We agreed to that. So instead of giving ‘special people’ of 25 years, something, just give something a little more to all the low income guys, make it fair to them.” He calls “unnecessary” Amendment 5 on this November’s ballot, which would index the second $25,000 homestead exemption to inflation.

The taxable value numbers in Flagler County and its cities won’t affect the School Board, which has no authority in setting school taxes and very limited authority in setting its budget. Most of that is done by the Legislature, which has consistently lowered the school tax rate year after year for almost two decades, lowering the most significant tax burden on local property owners (and cheating school districts of needed revenue). That has allowed other local governments to raise their taxes without necessarily affecting many taxpayers’ bottom lines, especially among the homesteaded, since the net result, when school tax cuts are included, has been little to no effective overall tax increases.

Atwp says

If taxable values increased over last year, why raise taxes on residents for the sheriff department? The audit education will cost a lot of money, will the increased tax value help decrease the tax cost to the residents? Just asking. People in Palm Coast are seeing tax increases very consistent.