The Ten Books of Christmas: Between Christmas and New Year’s FlaglerLive customarily reduces production. It helps us, and no doubt you, exhausted reader, to take a break from outrage and lurid politics. This year I’m doing something a little different. Instead of only running the usual end-of year sum-ups and fillers, I’m launching the Byblos column and offering the Ten Books of Christmas: every day I’m publishing an original piece of mine on one of the books of the year I found most notable—books old and new, fiction and nonfiction, whether inspired by covid, confinement, covfefe or just the libidinous, inebriating pleasure of reading. No doubt only six or seven readers out there are interested in this sort of thing. That's OK. They’re ignored the rest of the year, so this is for them. I hope they find these, ahem, brief reflections (rather than reviews) at least a little provocative. The days' installments are listed below. --Pierre Tristam |

![]()

In April 2020 the Centers for Disease Control published a study about the way the novel coronavirus spread through two families. A man had attended a birthday party, a funeral and a dinner, unaware that he had been infected. He spread the disease to 15 people, three of whom died. In keeping with clinical studies, the superspreader is not identified.

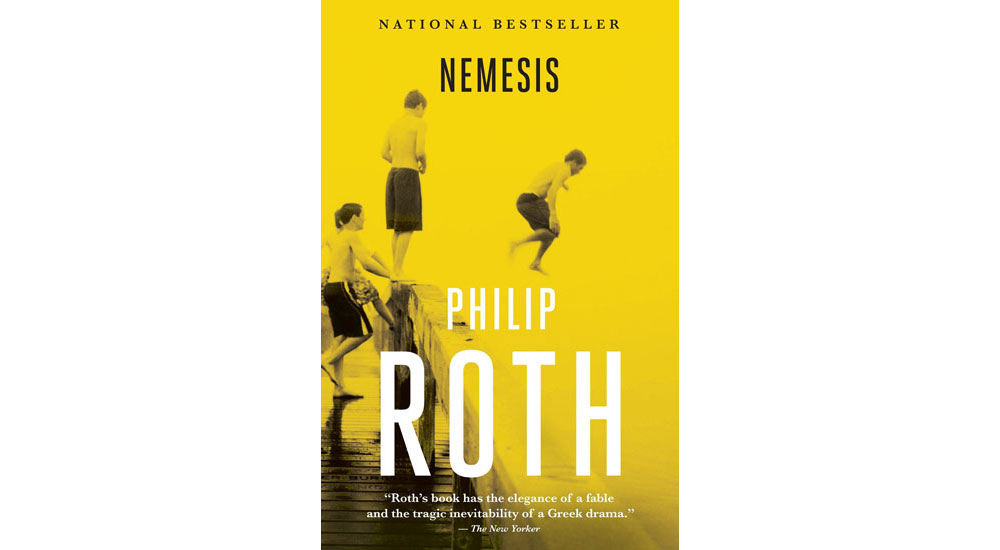

Philip Roth’s Nemesis is the story of that unsuspecting Everyman. This brief novel of viral massacres will seem as current to our plagues as this morning’s covid numbers, minus the ideological fury. But not the blame. Maybe most Everymen who spread disease and kill never know it, or don’t care. There’s been at least some of that in this pandemic. Bucky Cantor, the character at the center of the novel, unsuspectingly infects others with polio, but cares very much when he realizes it. Some of his victims die. He contracts it. He is crippled by it. His fiancee, whose sister he’d also infected with a mild case, doesn’t mind. He does, and rejects her. “I owed her her freedom,” he tells the book’s narrator, “and I gave it to her. I didn’t want the girl to feel stuck with me. I didn’t want to ruin her life. She hadn’t fallen in love with a cripple, and she shouldn’t be stuck with one.”

Philip Roth’s Nemesis is the story of that unsuspecting Everyman. This brief novel of viral massacres will seem as current to our plagues as this morning’s covid numbers, minus the ideological fury. But not the blame. Maybe most Everymen who spread disease and kill never know it, or don’t care. There’s been at least some of that in this pandemic. Bucky Cantor, the character at the center of the novel, unsuspectingly infects others with polio, but cares very much when he realizes it. Some of his victims die. He contracts it. He is crippled by it. His fiancee, whose sister he’d also infected with a mild case, doesn’t mind. He does, and rejects her. “I owed her her freedom,” he tells the book’s narrator, “and I gave it to her. I didn’t want the girl to feel stuck with me. I didn’t want to ruin her life. She hadn’t fallen in love with a cripple, and she shouldn’t be stuck with one.”

The culprit here isn’t the virus, the president, the public health agency, the media. It’s not personal or social responsibility. To Roth, who wrote this book as his last, if not yet knowing it was his last, it’s God, “a sick fuck and evil genius” who kills mothers in childbirth, puts 12-year-old boys in pine boxes and sticks His schiv in people’s backs for sport. God who “made the virus.” Clearly, Roth was not mapping his way to heaven.

This is around the time when he’d advised a young novelist to hang a sign above her desk that says: “It’s not going to get better, resign yourself to this,” and when he wrote of Bucky Cantor that “He does not accept the tragedy of it,” meaning his own illness and disfigurement, “that’s the tragedy because he has to pay the price. He transforms the tragic into guilt.” (Those were Roth’s notes for the novel, according to Blake Bailey in his recent biography of Roth, ridiculously cancelled for different reasons.)

As angry as Roth’s books tend to be, this is his angriest and most single-mindedly accusing on a shelf full of angry books. All of Roth’s work is score-settling (with ex-wives, with his identity, with the 1960s, with his internal Palestinian-Israeli conflict, with political correctness, with lost virilities and enduring puritanisms). Nemesis is score-settling on a divine scale.

His hero blames God for denying the agency of personal responsibility. Roth had read Camus’ Plague, “largely to avoid accidentally repeating any of his scenes or motifs,” according to his notes. I don’t think avoidance worked. There is a dialectic between Camus and Roth. God is a central theme in The Plague, too, if in a more damning, more liberating way than Roth allows. Camus eliminates God as an agent, as any kind of factor, reducing everything to chance, to human agency within chance. Roth’s Bucky might find that less satisfying than screaming at God. But he won’t let go of the anger, in effect empowering God at his expense. “You lose, you gain–it’s all caprice. The omnipotence of caprice,” Simon Axler tells his shrink in The Humbling, Roth’s penultimate novel. Bucky Cantor did not learn that lesson.

Bucky is 23 as Nemesis opens. “His was the cast-iron, wear-resistant, strikingly bold face of a sturdy young man you could rely on.” The sentence, so muscular as to suggest invulnerability, is a set-up, one of the early jokes played on Bucky–by God, played here by Roth. Bucky is a phys-ed teacher but school’s closed for summer. Because of his poor vision he’s a playground director in Newark’s Jewish Weequahic section instead of an infantryman in the European or Japanese war theater, like two of his friends. He feels the difference as a dereliction. It’s one of the angers that will eat at him, morally and physically, in the months that follow.

Polio in the 1940s was causing between 1,000 and 2,000 deaths a year, and infecting many more people, particularly children. Roth in Nemesis imagines an outbreak in Newark. “In a way I was imagining a menace we never encountered in all its force,” he told NPR’s Robert Siegel. “I wanted to imagine what it would have been like, in our neighborhood, had the menace [of polio] struck.” (A novelist one day will imagine Roth in 2020 sparring with Trump’s plot against America.)

The outbreak starts in the Italian section of Weequahic and soon spreads to the Jewish section, coincidentally after a gang of Italian teens bully Bucky and his children and spit at Bucky’s foot. “We’re spreadin’ polio,” one of the Italians tells Bucky. “We got it and you don’t, so we thought we’d drive up and spread a little around,” a scene reminiscent of that goon who went around the lobby of the Government Services Building at a school board meeting last August, purposefully coughing on the masked. (The malice of contagion is an old instinct.) Bucky stands up for his children, cleans up the goons’ mess and moves on. But the disease has spread.

If William Maxwell in They Came Like Swallows and Mary McCarthy in the first chapter of Memories of a Catholic Girlhood managed to recreate for the reader the grief-splitting silence of children’s incomprehension at the loss of their mother and father–Maxwell’s mother and both of McCarthy’s parents were felled quickly by the 1918 influenza epidemic–Roth in a few p[ages, in a few lines, recreates the silence of a boy’s casket: “It was impossible to believe that Alan was lying in that pale, plain pine box merely from having caught a summertime disease. That box from which you cannot force your way out. That box in which a twelve-year-old was twelve years old forever. The rest of us live and grow older by the day, but he remains twelve. Millions of years go by, and he is still twelve.”

By the novel’s end Bucky Cantor will feel responsible for infecting and killing some of the playground children he thought he was protecting, then some of the adolescents at a summer camp in the Poconos. He’d joined his counselor-fiancee there, thinking he was escaping the plague–and feeling more dereliction for abandoning his playground wards. He was only spreading the plague further. He was what we have learned to call an asymptomatic carrier. ( In plagues everyone acquires the language of contagion.)

When one, then another, then a third camper got it, he realized he’d been the spreader all along–a superspreader. He’d been sitting round the campfire, singing “God Bless America” and nursing “the memory of the great college friend who had not been out of his thoughts since he’d learned of his death fighting in France,” and all along he was spreading disease. A dozen campers, including his fiancee’s sister, got it. He is eventually hooked to an iron lung but survives, his body and ambitions maimed.

There are no culpable victims in plagues just as there are no culpable civilians in wars. They foment fear above understanding and create endless opportunities for mischief, not just for the virus. Plagues put us in our place, our small, brittle place in the universe or our neighborhood, our quarantine room, our ICU bed. They also remind us of “what we learn in a time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise” That’s Camus. Roth objects.

With Sabbath’s Theater, American Pastoral and The Human Stain, Nemesis is among Roth’s best works. But unlike Mikey Sabbath or Coleman Silk, there’s no sense of liberation for Bucky Cantor. He boxes himself in. Like his fiancee Marsha (not the most realized character in the book: Roth’s women, McMahons to his Carsons, seldom are) you want to slap him around, set him free. He refuses. His fixation on God’s responsibility is also, to me, the novel’s limitation.

Before you go accusing Roth of blasphemy, recall that ascribing motives to God in the midst of plagues and catastrophes is as old as plagues and catastrophes, though the accusations are usually directed at human beings in relation to God, and are meaner than anything Bucky Cantor cooked up. Just think of the way Americans reacted to the AIDS pandemic for so long, pretending it did not exist or casting it in the accusatory language of victim-blaming and divine retribution. In the talib-like words of Jerry Falwell, “AIDS is a lethal judgment of God on the sin of homosexuality and it is also the judgment of God on America for endorsing this vulgar, perverted and reprobate lifestyle.”

Falwell turned the existential crisis plaguing the sick into their infliction of an existential crisis for the nation: “[I]f we don’t do something with our wholehearted vigor and earnestness we are going to watch our nation die.” (Contrast the slaughterhouse callousness with how Jordan Roth, president and owner of one of Broadway’s three theater chains, described the effect of the human loss on the community: “An entire generation of artists and storytellers is gone, and our community is still grappling with that. There’s a huge, gaping hole where there should be lives.”)

In fairness to Falwell he also thought the 9/11 attacks were God’s retribution for too many homosexuals, and he thought the 1978 assassination of Harvey Milk, San Francisco’s gay mayor, was “of divine origin.” Falwell died in 2007, but his gay obsesson lives on: a Ukranian priest, Donald Trump’s White House minister and an Israeli Rabbi, to name a few, have all blamed the covid pandemic on gays, as of course have Muslim prelates, who tend to bash gays five times a day.

I’m not so sure there’s much difference between the Falwells of the world and Bucky Cantor’s response to his plague: blaming or crediting God either way is equally absurd. In Cantor’s case, it’s self-destructive, adding to, not challenging, God’s tally.

The Plague in comparison pulls off a magic trick. It is a search for meaning–as was Bucky’s–that resigns itself to the realization that there is no meaning, that meaning is unnecessary. Searching for meaning in the face of human misery is self-indulgence. Living for the sake of living is meaning enough, especially when there’s work to do: people are dying all around Dr. Rieux. To ponder the meaning of life at such a moment would make him an accomplice to murder–as would (or so suggests Camus) Father Paenloux’s week of collective prayer, or blaming infidels. It isn’t just courage but the ultimate courage to set meaning–and thoughts and prayer–aside and roll up one’s sleeves: life in the face of the incomprehensible, the unknowable, even the catastrophic, is life lived at its most meaningful. As Dr. Rieux put it, turning life-ending horror on its head: “But what does that mean, ‘plague’? Just life, no more than that.” (“Mais qu’est-ce que ça veut dire, la peste ? C’est la vie, et voilà tout.” The play on words of that c’est la vie is sublime.)

I first read Nemesis in 2010 and liked it less than I did on second reading, when most of us were unsuspecting of another plague nearing the scale of the 1918 influenza, though we had no right to be. Plagues are not the exception we assume them to be. Plague literature goes back to Thucydides, Galen, Boccaccio’s Decameron, Defoe’s fictionalized Journal of the Plague Year, the innumerable chroniclers of the 1918 influenza (Maxwell’s Swallows will make you a masker for life), Camus, and just before the Covid pandemic, Geraldine Brooks’s Year of Wonders (set in the London of 1666) and, even more strikingly, Lawrence Wright’s The End of October, a contemporary fiction about an infected man who travels to Mecca for the Hajj and launches the biggest superspreading event of the ages. Wright had completed his novel just as Wuhan was becoming as familiar as Gotham.

I’m writing this as covid deaths worldwide have reached 5.5 million, and 846,000 in the United States. Maybe Bucky Cantor is onto something, schiv and all, though maybe Bucky should have also listened to his fiance’s father, another doctor–Dr. Steinberg–when he told him, Rieux-like: “This is America. The least fear the better. Fear unmans us. Fear degrades us. Fostering less fear–that’s your job and mine.” And not just theirs.

![]()

Pierre Tristam is the editor of FlaglerLive. Reach him by email here.

Leave a Reply