By Simon Chadwick

Pelé, soccer’s first global superstar, has died at the age of 82. To many fans, the Brazilian will be remembered as the best to have ever played the game.

For others it goes further: He was the symbol of soccer played with passion, gusto and a smile. Indeed, he helped to forge an image of the game, which even today lots of people continue to crave.

Pelé wasn’t just a great player and a wonderful ambassador for the world’s favorite game; he was a cultural icon. Indeed, he remains the face of a purity in soccer that existed long before big money and global geopolitics infiltrated the game.

It is testament to his legend that everyone from English 1966 World Cup winner Sir Bobby Charlton and current French superstar Kylian Mbappé to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – the former and incoming president of Brazil – and former U.S. President Barack Obama have led tributes to him.

Early days at Santos

Pelé was born Edson Arantes do Nascimento in Sao Paolo state, Brazil in 1940. His early years were the same as many soccer players who preceded him and countless who then followed and were inspired by him: born into poverty, introduced to the game by a family member, later becoming obsessed by a sport that taught him about life and gave him opportunities.

Youth team football came first, in 1953, when he signed for his local club, Bauru. But it was his first professional club, Santos, that propelled Pelé toward stardom. Having moved there in 1956, he played 636 matches and scored 618 goals before leaving in 1974. Not just the beating heart of the team, Pelé was also an immense, one-club loyalist.

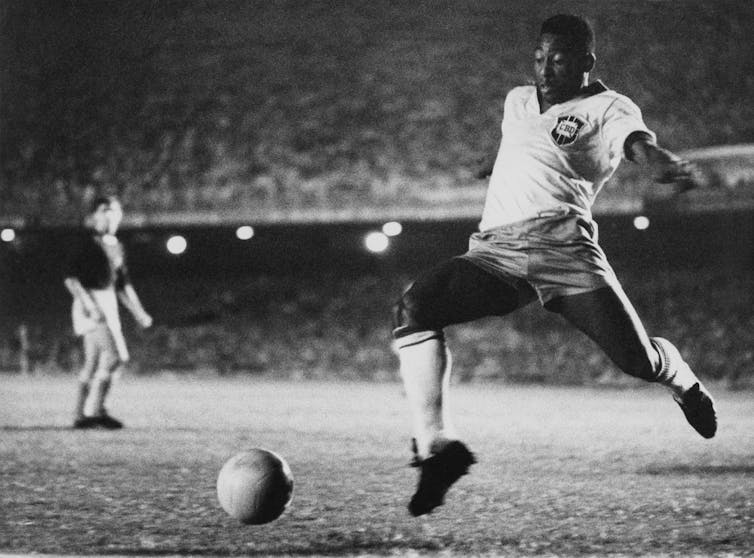

Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Long before the feats of modern-day stars Cristiano Ronaldo or Erling Haaland, Pelé blazed a goal-scoring trail that marked him out as being significantly different to other players around him. Similarly, he displayed levels of skill which even today mean that some observers of the game place the Brazilian ahead of the likes of other contenders for the title of Greatest of All Time: Lionel Messi and Diego Maradona.

Within a year of signing for Santos, Pelé made his debut for Brazil, three months short of his 17th birthday. He scored in that game against Argentina, and 65 years later he remains the Brazilian national team’s youngest-ever scorer.

A year later, in 1958, this young player helped his national team win the World Cup in Sweden. Then again in 1962, at the World Cup in Chile, and once more at the 1970 tournament in Mexico.

Ultimately, Pelé played 92 times for Brazil, scoring 77 goals. By comparison, England’s Harry Kane has scored 53 times in 80 matches. In addition to his national team achievements, for his club Pelé won six Brazilian league titles and two South American championships.

The American years

Later, in 1975, he came out of semi-retirement to play for the New York Cosmos in the North American Soccer League. By then, Pelé was in his mid-30s but still managed to score 37 goals in 64 matches. Some believe that it was his brief stint playing in the United States that kick-started the country’s interest in football.

After his retirement, Pelé was venerated, adored and remained influential. He became FIFA’s Player of the 20th century, an award he shared with Maradona. In 2014, he was given FIFA’s first-ever Ballon d’Or Prix d’Honneur, and even Nelson Mandela spoke of his regard for the Brazilian when presenting him with a Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award, in 2000.

Pelé’s talent has never been in doubt. Yet it was fortuitous that he played at a time when soccer was emerging from the shadows cast by global conflict, when the world needed symbols of hope and sporting heroes.

The Brazilian was able to serve this purpose, though he did so during a period when television – first black-and-white, then color – brought soccer directly into people’s living rooms. At the time, Pelé was Messi, Ronaldo and Mbappé rolled into one – made globally consumable by this new technology.

Inevitably, during his life, Pelé encountered problems: his commercial activities were sometimes mired in controversy; at one stage he was labeled a left-wing antagonist of the Brazilian government, then was later described as being too conservative in his views of the Brazilian dictatorship. He had numerous children – some the result of affairs – and one of them, a son, Edinho, was sent to prison for laundering money made from drug deals.

However, the abiding memory is of a man who played soccer in a way that many of us – both amateurs and professionals – have all aspired to. Pelé was not only skillful, he also brought great joy to innumerable people across the world, over a period of decades. For all of us, even those with just the slightest interest in football, we will never forget him.

![]()

Simon Chadwick is Professor of Sport and Geopolitical Economy at SKEMA Business School.

DARRELL SMITH says

He dominated his sport like no on I’ve ever seen. And in his generosity he was the only sportsman above Roberto Clemente and Muhammad Ali.

William Moya says

I cannot comment on Roberto Clemente, I am a big fan of Pele and said so recently in a Tweet during the World Cup, a man who never forgot who he was and where he came from, the Brazilian government “labeling him a left wing antagonist” is part and parcel of the, now diminishing number, of fascist governments throughout Latin

America, bur Muhammad Ali deserves a special place, he had to face a racial political struggle against a society deeply embedded in American society, and paid a huge price for his stance against a regime the for him was as authoritarian as they come, so three cheers for Muhammad Ali, from someone who came to late to the fight.