By Chris McCahill

The U.S. has a car-centric culture that is inseparable from the way its communities are built. One striking example is the presence of parking lots and garages. Across the country, parking takes up an estimated 30% of space in cities. Nationwide, there are eight parking spots for every car.

The dominance of parking has devastated once-vibrant downtowns by turning large areas into uninviting paved spaces that contribute to urban heating and stormwater runoff. It has driven up housing costs, since developers pass on the cost of providing parking to tenants and homebuyers. And it has perpetuated people’s reliance on driving by making walking, biking and public transit far less attractive, even for the shortest trips.

Why, then, does the U.S. have so much of it?

For decades, cities have required developers to provide a set number of parking spaces for their tenants or customers. And while many people still rely on parking, the amount required is typically far more than most buildings need.

Columbus, Ohio, pioneered this strategy 100 years ago, and by the middle of the 20th century minimum parking requirements were the norm nationwide. The thinking was straightforward: As driving became more common, buildings without enough parking would clog up the streets and wreak havoc on surrounding communities.

Today, however, more urban planners and policymakers acknowledge that this policy is narrowly focused and shortsighted. As a data scientist who studies urban transportation, I focused my earliest research on this topic, and it shaped how I think about cities and towns today.

It’s encouraging to see cities rethinking minimum parking requirements – but while this is an important reform, urban leaders can do even more to loosen parking’s grip on our downtowns.

Eliminating parking requirements

Despite research and guidance from the Institute of Transportation Engineers, it is extremely difficult to predict parking demand, especially in downtown areas. As a result, for years many cities set the highest possible targets. This led to excess parking that is vastly underused, even in areas with perceived shortages.

In 2017, Buffalo, New York, became the first large U.S. city to eliminate its minimum parking requirement as part of its first major overhaul of zoning laws in more than 60 years. This shift has breathed new life into downtown Buffalo by spurring redevelopment of vacant lots and storefronts. Researchers estimate that more than two-thirds of newly built homes there would have been illegal before the policy change because they would not have met the earlier standards.

In the same year, Hartford, Connecticut, followed Buffalo’s lead and eliminated mandatory parking minimums citywide. Communities including Minneapolis; Raleigh, North Carolina; and San Jose, California, have since taken similar steps.

Tony Jordan, president of the nonprofit Parking Reform Network, has argued that once cities stop mandating specific levels of private parking, leaders need to be more thoughtful about how they manage public curbside parking and spend the revenues that it generates. Some communities have implemented maximum parking allowances to ensure that developers and their investors don’t add to the glut.

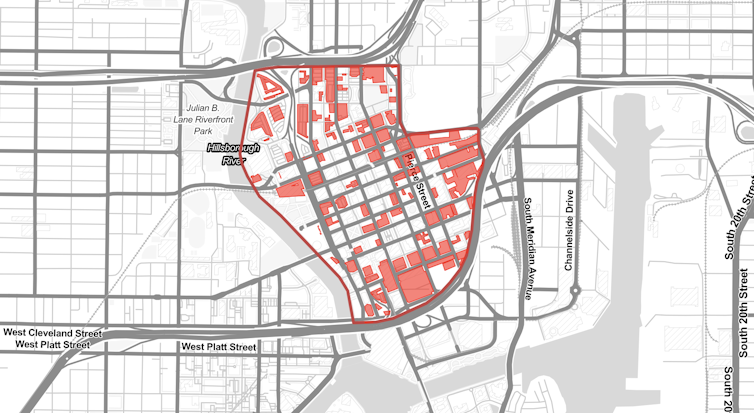

Parking Reform Network, CC BY-ND

Reducing reliance on cars

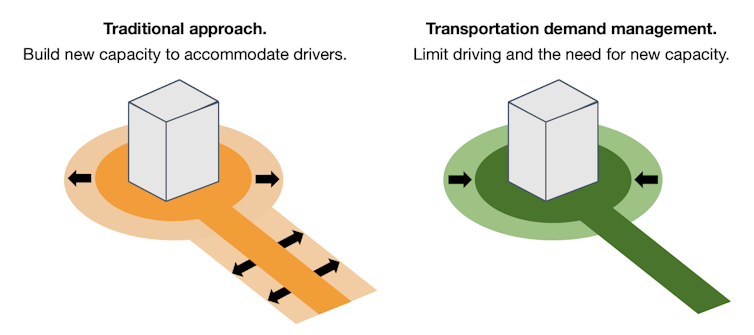

Parking mandates aren’t the only lever that city officials can use to make their downtowns less car-centric. Some local governments are now asking developers to help reduce overall traffic levels by investing in improvements like sidewalks, bike storage and transit passes.

This approach is typically called transportation demand management, or modern mitigation. It still leverages private investment to serve the public good but without a singular focus on parking.

And unlike parking requirements, this strategy helps connect buildings to their surrounding communities. As urban planning scholar Kristina Currans explained to me in an interview, traditional parking requirements ask developers to fend for themselves. In contrast, transportation demand management policies require them to consider the surrounding context, integrate their projects into it and help cities function more efficiently.

City of Madison, adapted by Chris McCahill, CC BY-ND

This approach dates back at least to 1998, when Cambridge, Massachusetts, introduced a policy requiring developers to produce a transportation demand management plan whenever they add new parking. That policy has now outlived the city’s minimum parking requirements, which Cambridge eliminated for all residential uses in 2022.

Newer policies tend to incorporate point systems or calculators that link different strategies directly to their potential impact on car use. These tools are common in cities across California, where state law now requires city planners to evaluate how much new car use each new development will generate and take steps to limit the impact. Policies such as charging users directly for parking spots or offering employees cash in exchange for giving up their spot are among the most effective.

Denver Regional Transportation District

Lessons from Madison

The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s State Smart Transportation Initiative, which I direct, along with UW’s Mayors Innovation Project, has outlined policies like these in a guide based on our earlier work with the city of Los Angeles. We recently collaborated on a new transportation demand management program in Madison.

This program initially faced some pushback from developers, but their input ultimately made it better. It passed the city’s Common Council unanimously in December 2022.

For their projects to be approved, developers now must earn a certain number of traffic mitigation points based on how large their project is and how many parking stalls they propose to include with it. For example, providing information to visitors and tenants about different travel options earns one point; providing secure bike storage earns two points; offering on-site child care earns four points; and charging market-rate parking fees is worth 10 points. Scaling back planned parking can reduce the number of points they need to earn in the first place.

While parking is no longer required in many parts of Madison, this new policy adds a layer of accountability to ensure that developers provide access to multiple transportation options in environmentally responsible ways. As urban leaders look for meaningful opportunities to reduce their cities’ contributions to climate change, we may soon see other cities following suit.

![]()

Chris McCahill is Managing Director of the State Smart Transportation Initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

JimboXYZ says

So we’re back to see how many can go without the freedom to conduct their private affairs in a city/county that really is designed as car centric. Those bike share things don’t work. It’s a bike rental scheme is all that is for tourists. Trust me, I saw it in Miami. The rate for riding the bike and that cost is close to what driving a car around. We have thunderstorms roll in every day, sometimes several times a day. Nobody wants to be stuck miles from home when the downpour happens. Essentially we’re back to strategies that essentially make everyone like the homeless for transportation. Seriously, how many homeless do you see driving a car beyond those that actually live in/out of their automobile as early stages of homelessness. The next step is rent subsidies and no car. That’s Bidenomics. Saving the planet requires that the masses go without a car. That’s how they intend to reduce consumption, price the masses out of affordable transportation & fuel. We all might as well go back to the horse & buggy days. Miami already has developers that aren’t providing adequate parking for the number of units they build, even with parking space minimums.

JimboXYZ says

Set aside 2:45 hours and watch this. The reality of what America & the world is on a trajectory. You’ll figure out 8 billion growing to 10 billion this century, who will have & who goes without. Who is allowed to flourish, who is only here to exist to be the slave, becoming Biden-Harris pets.And coincidentally Obama-Biden. You don’t need a college degree to figure this out, not when it’s a 3 hour block of your time to have it explained for an internet stream.

Denali says

Developers cannot control anything outside their property lines. If a city wants to require developers to provide a traffic flow plan based on the anticipated needs of the new project, that is entirely reasonable. The city can then adjust the required on-site parking and make the appropriate changes to the cities public transportation system. In looking at our own city City Walk is a perfect example of too many parking spots allocated for the amount of traffic the project gets whereas Island Walk is a disaster in both layout and capacity. And what happened at Epic Theater? One space for every seat? At least it looks like that was the plan.

The bigger issue here is the lack of planning by previous generations. No amount of patches made today can correct the fact that Palm Coast is not and never will be a bicycle friendly city. Just cannot see myself pedaling eight miles to the hospital for a doctors appointment or the two miles to Publix for my weekly grocery shopping (problem is the return trip with the groceries). With no public transportation a personal vehicle becomes a must have item.

In rural areas this becomes a bigger issue. Our farm up north is 12 miles from town. No busses are available and a bicycle is out of the question. But then again, I have never seen any of the parking lots at over 50% capacity, unless you head to Starbucks. Again a personal vehicle is a must have.

I have worked in major metropolitan areas where owning a car was a mistake, you walked, grabbed a cab or other public transportation and went about your business. In the ‘old days’ I could walk to the corner market for my groceries – those stores are mostly memories now. The only need for a personal vehicle was to get out of the city and have the freedom to roam at will.

Bottom line is that developers cannot make the changes needed to accommodate a reduction in on-site parking until a third party steps in and provides the infrastructure to safely and efficiently move people through the urban environment. Additionally, urban areas must rethink land use. It is wonderful to consolidate all the goods and services in one central location but to do so only increases the need for more vehicle parking and public transportation. De-centralizing the cities would create an environment where people could actually walk or ride a bike to the store.

In the meantime the American love affair with our cars will continue and I will keep mashing the clutch, grabbing gears on the Muncie and listening to the music of the 413 cross ram 4 bbl Holleys.

bob says

Hog wash … developers should be required to traffic flows & etc, to blankly say they cannot do anything outside property lines is a loser statement immediately after you open a Cracker Jack box … put rear baskets and a front basket on your bike, you’ll improve your health when miking cows 12 miles from town … something poeple are so smart they are stupid

Land of no turn signals says says

Been out much?Try parking at the new Planet Fitness.Bronx house pizza shopping center on route 100.It’s a zoo most of time.

dave says

Agree with the Bronx PIzza place. IF you don’t have a compact car, forget about it.

As far as Riding a bike, from where, in what heat and weather. Grocery store on a bike that should be a hoot. With all the elderly drivers, I wonder what the bicycle rider injury toll would be .

Oh PS, from 7 days ago ” Data from the Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles (FLHSMV) shows that in 2022 Hillsborough County saw 305 bicycle accidents, resulting in 14 deaths and 271 injuries. In Pinellas County for the same year, 388 bicycle crashes were reported resulting in 9 deaths and 374 injuries.”

Sherry says

This entire story only seems relevant to “major” urban areas where “public transportation” systems are well developed and utilized. The development of excellent clean energy public transportation must be implemented, and adopted fully by the local populace, BEFORE expecting the general public to give up their cars.

Jimbo99 says

The plan is to connect the major metros with growth. Jacksonville leaked into St Augustine, Daytona/Ormond Beaches are leaking growth into Flagler. St Augustine has nowhere to grow but into Flagler county. As the population grows, eventually the entire East coast of FL becomes a continuous conglomeration of townships. The actual mileages never change, but effectively FL becomes more like the NE USA or even England. Back around 2009/2010-ish the expansion of high speed rail was to include Miami => Orlando, that’s called Brightline High speed trains will become the transportation in theory. End of the day, we’ll all be walking to or riding a bicycle to a high speed rail station to take the train elsewhere for a commute. Those fortunate enough may work from home ?

Brightline doesn’t really work well for anyone that is too far from a rail station for convenience really. They didn’t really think that thru. The rail in Miami depending upon your perspective begins & ends at SW 88th station. There was talk it would eventually extend to Key West as it runs next to US-1. But imagine a rail system that would eliminate US-1 for 120 miles to the FL Keys, I mean we all see the remnants of how the Henry Flagler rail system turned out & that runs from Maine to the FL Keys as one railroad or another.

That’s the concept as a solution, replace your car & it’s costs with a rail system that’s inconvenient and costs pretty much what unless you have a monthly pass. You’d have to live on top of a railroad track & hear that noise all day long. When I lived in North Miami Beach, I lived at West Dixie Highway, which is next to US-1, which is next to the railroad tracks. During the day, it’s not bad, but at night, it’s a sleep disruption.

https://www.gobrightline.com/

dave says

Yes, that’s the big plan, trains between all the big cities, novel huh !.

” at night, it’s a sleep disruption”, got that right.