To include your event in the Briefing and Live Calendar, please fill out this form.

Weather: Partly cloudy. A slight chance of showers and thunderstorms in the morning, then showers and thunderstorms likely in the afternoon. Highs in the lower 90s. South winds 5 to 10 mph. Chance of rain 60 percent. Saturday Night: Partly cloudy. Showers and thunderstorms likely, mainly in the evening. Lows in the lower 70s. Southeast winds 5 to 10 mph. Chance of rain 60 percent. Check tropical cyclone activity here, and even more details here. See the daily weather briefing from the National Weather Service in Jacksonville here.

Today at a Glance:

The Saturday Flagler Beach Farmers Market is scheduled for 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. today at Wickline Park, 315 South 7th Street, featuring prepared food, fruit, vegetables , handmade products and local arts from more than 30 local merchants. The market is hosted by Flagler Strong, a non-profit.

Gamble Jam: Musicians of all ages can bring instruments and chairs and join in the jam session, 2 to 5 p.m. . Program is free with park admission! Gamble Rogers Memorial State Recreation Area at Flagler Beach, 3100 S. Oceanshore Blvd., Flagler Beach, FL. Call the Ranger Station at (386) 517-2086 for more information. The Gamble Jam is a family-friendly event that occurs every second and fourth Saturday of the month. The park hosts this acoustic jam session at one of the pavilions along the river to honor the memory of James Gamble Rogers IV, the Florida folk musician who lost his life in 1991 while trying to rescue a swimmer in the rough surf.

Grace Community Food Pantry, 245 Education Way, Bunnell, drive-thru open today from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. The food pantry is organized by Pastor Charles Silano and Grace Community Food Pantry, a Disaster Relief Agency in Flagler County. Feeding Northeast Florida helps local children and families, seniors and active and retired military members who struggle to put food on the table. Working with local grocery stores, manufacturers, and farms we rescue high-quality food that would normally be wasted and transform it into meals for those in need. The Flagler County School District provides space for much of the food pantry storage and operations. Call 386-586-2653 to help, volunteer or donate.

St. Augustine Book Festival: The Ximenez Fatio House Museum, 20 Aviles Street, Saint Augustine, is hosting the St. Augustine Book Festival on the first three Saturdays of September, featuring literary events that include historic house tours, author meet and greets, author presentations, book signings, local attractions, and more at the Ximenez-Fatio House Museum. Today’s Author Presentation Schedule:

11:00am: Marta Magellan (children’s nature)

2:00pm: Marisa Carbone (children’s history)

Reservations will be available for up to 15 guests for each tour and can be booked online at $15 for adults; $8 for children 6-18; and $12 tickets for seniors, military, and teachers. Buy tickets.

St. Augustine Ballet 6th Annual International Dance Festival Gala: 7 p.m., Lewis Auditorium, 14 Granada Street, St. Augustine. The St. Augustine Ballet & Conservatory presents its 6th annual International Dance Festival Gala at Flagler College. As part of the annual International Dance Festival, intermediate and advanced ballet students and instructors showcase their mastery of several dance styles during the performance on Saturday. Adults: $20.00, Students/Children: $10.00. Tickets may be purchased online or at the door at 6:00 p.m. on the night of the show.

In Coming Days:

September 16: Flagler OARS’ 3rd Annual Recovery Festival at Veterans Park in Flagler Beach, from 3 to 9 p.m., with live bands, food trucks, exhibitors, hosted by Open Arms Recovery Services. Vendor booth space and sponsorships available. Click here or contact [email protected].

Keep in Mind: The Belle Terre Swim & Racquet Club is open, welcoming and taking new memberships, and if you enroll before Sept. 1, you’ll beat the price increase kicking in then. Experience the many amenities including a lap pool, wading pool, tennis/pickleball courts, sauna, and a modern wellness center–all for less than what you’d pay just for a fitness center at your typical commercial gym. Friendly staff is available to answer any questions you may have about becoming a member. Belle Terre Swim and Racquet Club is the sort of place where you can connect with fellow community members and experience the welcoming atmosphere that sets BTSRC apart. If you have any questions, feel free to call at 386-446-6717. If you would like to learn more about our club and membership options please visit online.

Storytime: Bellarosa is Italian for “beautiful rose.” It is how Harry Fonstein mishears the name of his savior, Billy Rose, a sordid Broadway impresario who, we never knows from what motivations, had a side gig saving Jews from the Holocaust. Harry Fonstein is saved while in Rome. He will never know why. He makes it to the United States, marries Sorella, a woman as corpulent as William Howard Taft, and becomes very successful except in one regard. He is unable to meet Billy Rose, ever, either to thank him or to find out why Rose saved him. Rose doesn’t want to have anything to do with him, just as he apparently doesn’t want to have anything to do with anyone else he saved. He is too busy indulging his power. I don’t know why he should owe those he saved an explanation. They’re not his wards. But that’s the hinge of The Bellarosa Connection, one of two novellas Bellow issued in paperback in 1989 (The Actual, rejected by The New Yorker and The Atlantic, ostensibly for being too long, was the other). The story is told by an anonymous narrator, himself a millionaire founder of a memory institute–the Mnemosyne Institute in Philadelphia, not to be confused with the one-time Memnosyne Institute, a strange little non-profit that, along with its toggled m and n, looks more like a hoax. To be clear, Mnemosyne as Bellow intends it is the Greek goddess of memory and mother of the Muses. The institute in question trained important people in the mechanics of memory, but it doesn’t play a role here other than to frame the story: a reconstructed remembrance of Harry Fonstein, Sorella Fonstein and Billy Rose that asks a few questions without answering them, and that leaves the reader wondering what it’s really all about, other than an old man’s unsuccessful attempt to make that connection of the title. Unlike Bellow’s Augie March, his Herzog, his Humboldt, even his Blooms-deifying Ravelstein, the Fonsteins and Rose never come alive as more than types, despite Bellow’s attempt to make Rose seem like another Robert Moses. The novella’s insistent thread–chasing after Rose for an explanation for his good deed–doesn’t make sense: Rose has every right to be let alone, and his vulgarity is irrelevant (not every savior is a romanticized Schindler):

Billy was as spattered as a Jackson Pollock painting, and among the main trickles was his Jewishness, with other streaks flowing toward Billy secrecy–streaks of sexual weakness, sexual humiliation. At the same time, he had to have his name in the paper. As someone said, he had a buglike tropism for publicity. Yet his rescue operation in Europe remained secret.

Wonderful prose, but every line at once implying a whispered Nuremberg from one side of the courtroom and begging a so what from the other. The attempted and counterintuitive exploration of Jewish survival in the United States is daring, but goes nowhere: “The Jews could survive everything that Europe threw at them. I mean the lucky remnant,” Sorella tells the narrator. “But now comes the next test–America. Can they hold their ground, or will the U.S.A. be too much for them?” A radical question, but we never really know what would be too much, certainly not from a millionaire narrator and an apparently equally successful Fonstein, whose son is a math genius. There is a lot more about “the Americanization of the Jew,” a curious exploration, but nowhere distinguished from what could have been “the Americanization of the Vietnamese,” “the Americanization of the Arab,” “the Americanization of the Papuan.” Most of the novella centers instead on the narrator’s relationship with Sorella and Sorella’s fatness, an obsession that seems to have no relevance to the story other than as a running device for Bellow to make fun of the character his narrator claims to admire, though hardly a page goes by without one, two, four or five references to her fatness, most of them intended as comical, none of them pulling that off except maybe in the mind of the same imperious Bellow who, two years before The Bellarosa Connection, had told James Atlas of the New York Times Magazine: “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans? I’d be glad to read them.” Bellow denied saying that. I doubt his denial, considering how he referred six times to the fatness of Sorella in the space of a page and a quarter: “… there was a degree of fantasy embodied in Sorella’s obesity.” “She was biologically dramatized in waves and scrolls of tissue.” “It was good for a DP [displaced person] to have ample ballast in his missus.” She, who is fluent in French, refers to herself as “a femme bien en chair (a hefty woman). The narrator goes on, still on the same page, in the same paragraph: “I wondered how a man found his way among so many creases.” To which the disingenuous narrator adds: “But that was none of my business,” only to again return to the creases, supposedly quoting Sorella: “I should be carried in a litter.” By then the trustworthiness of the narrator is fully in question. He is not narrating the story of how unsuccessfully Sorella blackmailed Rose, when they all found themselves in Jerusalem in 1959, by forcing him to speak with her husband for 15 minutes or else (she had the incriminating diary of a former Rose secretary in hand, but soon lost it). Rather, he is narrating his obsession with Sorella (“lumpish,” “this painful record of disgrace,” “a huge lady,” “so extensive an organism”: four descriptions, all on the next page), making her fatness the axis of this loose, meandering novel. “I couldn’t keep from speculating on her expansion,” he writes. No, and that’s about all he speculates on with any precision. Precision as cruel and sometimes as cliche as “the mad overflow of her behind.” This is not mature Bellow so much as what might have been unpublished Evelyn Waugh juvenilia. The rest of the story hangs like so many folds from the Sorella subplot, enriched, as all Bellow works always are, by that irresistible whirling-dervish style of his, especially when he hooks it to his psycho-philosophical asides, though the lines are few: “Very few of us, for that matter, bother about accountability or keep spreadsheets of conscience.” Or: “… the ground bass of brutality, without which no human music is performed.” We get the sense that the narrator, or Bellow, is memorializing something for his own sake as if to use “memory, which is life itself,” as a means of prolonging life or, as the same line is echoed by a more candid admission at the end of the work, to concede that “memory is life and forgetting death.” If so, then the narrator is doing so at the expense of the Fonsteins and Rose, contriving a conflict where there really should not have been one. Thirty years later, prompted by a rabbi who needs to contact Harry, he tries to get in touch with the Fonsteins only to fall on their property’s house-sitter, learning that they have died in a crash on the Jersey Turnpike and their son has become a gambling addict, his math wizardry gone to shit. The narrator is remorseful not to have been in touch with them sooner, but we all are victims of delaying, f stocking that “warehouse of intentions” (another wonderful phrase in the book). It’s not enough to prevent Bellow from returning in the final pages to Sorella, “so mysteriously obese,” to “her cumulous body,” as he dreams of death: “Life so diverse, the Grand Masquerade of Mortality shriveling to a hole in the ground.” At least, at least, he concedes: “I hadn’t understood Fonstein v. Rose, and I badly wanted to say this to Harry and Sorella. You pay a price for being a child of the New World.” But again: I don’t know what the New World has to do with it. It is another contrivance, an overlay that doesn’t stick. Mnemosyne’s children have not inspired Bellow much in The Bellarosa Connection.

—P.T.

Now this: Philip Roth’s final interview: The Adventures of Saul Bellow

View this profile on Instagram

![]()

The Live Calendar is a compendium of local and regional political, civic and cultural events. You can input your own calendar events directly onto the site as you wish them to appear (pending approval of course). To include your event in the Live Calendar, please fill out this form.

January 2026

Temple Beth Shalom Blessing of the Pets

Nar-Anon Family Group

Palm Coast Charter Review Committee Meeting

Bunnell City Commission Meeting

Palm Coast City Council Workshop

Flagler Beach United Methodist Church Food Pantry

Community Preparedness Workshop

Flagler County School Board Information Workshop

Flagler County Affordable Housing Committee Meeting

Weekly Chess Club for Teens, Ages 10-18, at the Flagler County Public Library

Book Dragons, the Kids’ Book Club, at Flagler Beach Public Library

Budgeting by Values: A Virtual Class to Learn Budgeting Skills

NAACP Flagler Branch General Membership Meeting

Flagler County School Board Meeting

Random Acts of Insanity Standup Comedy

For the full calendar, go here.

![]()

His voice was instantly recognizable and inimitably his own: at once highbrow and streetwise, lofty and intimate – a voice equally at home ruminating on the great social and political ideas of the day, and chronicling the “daily monkeyshines” of “the cheapies, the stingies, the hypochondriacs, the family bores, humanoids” and bar-stool comedians who populate his cacophonous world. Indeed, Saul Bellow managed brilliantly, in the words of Philip Roth, “to close the gap between Thomas Mann and Damon Runyon.” In doing so, he captured a huge slice of American life: the human comedy as played out – often in that raucous, quintessentially American city of Chicago – in the backrooms, bedrooms, boardrooms and barrooms of the second half of the 20th century. Mr. Bellow once told a reporter that “for many years, Mozart was a kind of idol to me – this rapturous singing for me that’s always on the edge of sadness and melancholy and disappointment and heartbreak, but always ready for an outburst of the most delicious music.” And his own writing embraced the exuberant and the depressive, the rapturous and the dispiriting. There were extroverted, ebullient performances like “The Adventures of Augie March” (1953) and “Henderson the Rain King” (1959), which end with their heroes taking giant steps toward an affirmation of their lives, and crotchety, more claustrophobic volumes like “Seize the Day” (1956) and “Mr. Sammler’s Planet” (1970), infused with gripes and diatribes and desperate pleas for help. The novels, however, rarely stayed put on one side of the fence or the other: a dark preoccupation with mortality threaded its way through the comedy of “Humboldt’s Gift” (1975), and the best-selling “Herzog” (1964) managed to be tragic and comic, cerebral and earthy, meditative and manic all at the same time. These novels were less plot-driven works than portraits of men trying to figure out their place in the world, what it means, as Mr. Bellow wrote in “Herzog”: “to be a man. In a city. In a century. In transition. In a mass. Transformed by science. Under organized power. Subject to tremendous controls. In a condition caused by mechanization. After the late failure of radical hopes.”

–From Michiko Kakutani’s “Saul Bellow, Poet of Urban America’s Dangling Men,” The New York Times, April 7, 2005.

Laurel says

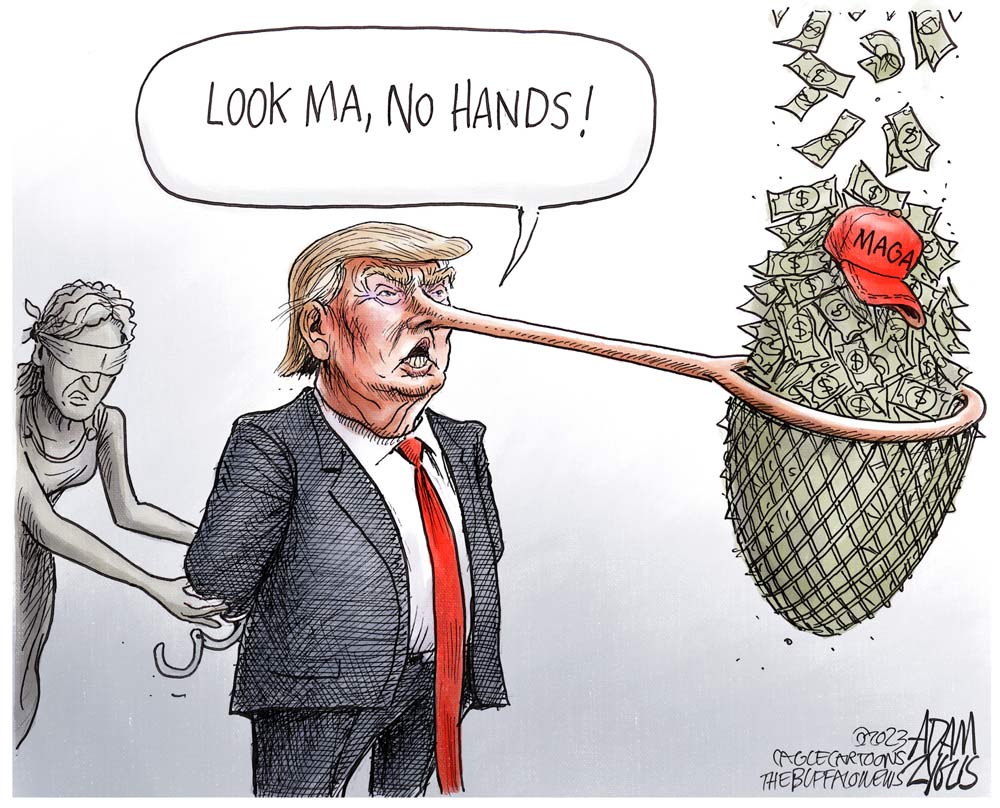

Trump is always exaggerating everything he does as the biggest, greatest, largest, etc. in the history of the universe. Well, now he is right. I believe he and his family have pulled off the biggest grifts in the history of human kind. Congratulations, Trump, you have pulled the wool over the most eyes since Hitler. Certainly grifted more money.

Albe says

I believe the trophy goes to Biden and the other democrats for destroying America.

Laurel says

Albe: No, America is still here.

Explain, exactly, with accurate backup, how you think America has been “destroyed.” Please be specific, and use your own judgement, not social media and Fox talking Entertainment (fined for lying about Dominion) talking points.

If you want to learn, without bias, go to YouTube and look up Frontline. There are excellent shows and interviews without the ridiculous conspiracies and one sided blabber.