If the jury was expecting to see a man demolished by his own claim that he was forced in self-defense to shoot his wife of “about a year or two” (as he described his marriage), to kill the woman he said he loved like no one else, the woman he said had understood him like no one else and with whom he was starting a new life in a new house, it’s not what the jury saw today.

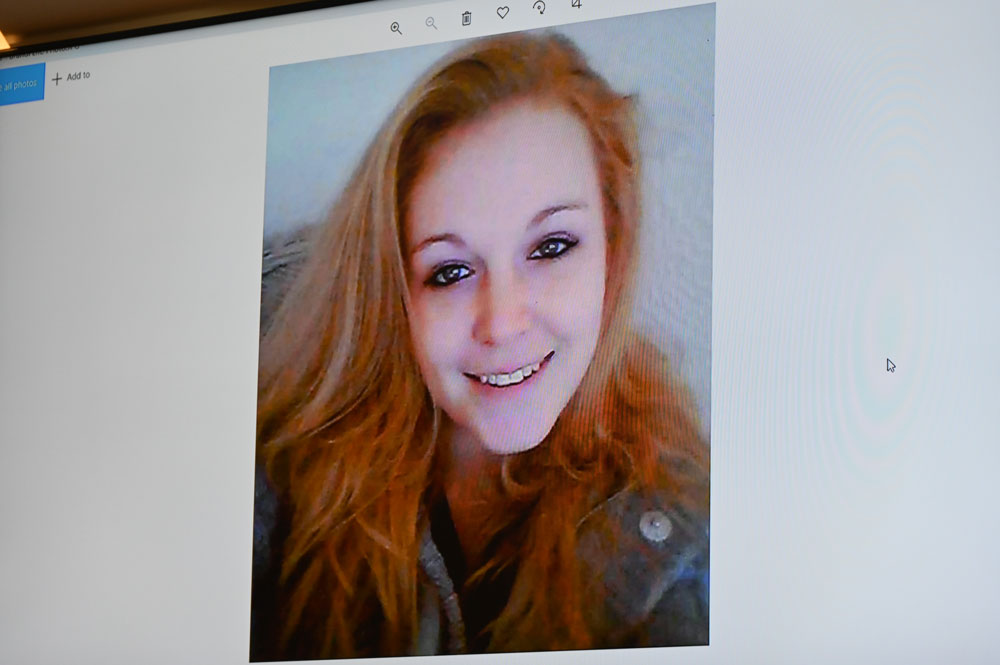

When 39-year-old Keith Johansen took the stand in his own defense on a charge of premeditated first degree murder in the third day of his trial this afternoon, the jury saw a testimony as impersonal and unemotional as that of the forensic weapons analyst they’d seen earlier in the day. The weapons analyst had explained how guns and bullets and gunpowder work. Johansen explained how he shot and killed 25-year-old Brandi Celenza: “Man, I wish I had a diagram to show you.”

He had described how he and Celenza smoked meth for 10 days, how he didn’t really mean it when he repeatedly demeaned and threatened her life (it was captured on video), how they’d fought for five hours two nights before the shooting, though calling it a fight as he did is a misnomer, at least based on the videos the jury saw: he berated, he insulted, he degraded, he threatened. Brandi endured and sobbed, and by night’s end was literally in the fetal position on her own bed. “That wasn’t a big fight?” the prosecutor asked him. “I mean, it was, but it wasn’t.”

Johansen explained, in the same tone, how he told the 911 operator that he didn’t want to touch her even as he was busy, “out of habit,” collecting pot and drug paraphernalia from the living room even as the dispatcher was telling him how to care for his wife. He admitted to lying to law enforcement for 12 hours and to his parents for at least 20 days. But he said he lied because he didn’t want to “tarnish” his wife’s name.

She was dead. But he didn’t want his parents and others to find out about her meth use.

He knew he was being recorded when he spoke with cops. So he knew there’d be an autopsy and Brandi’s meth use would not be a secret. But he stuck to his initial lies that she’d killed herself (not quite a way to help her name in a stigma-ridden society) or that it was an “accident” to protect a name he now, on the stand, couldn’t bring himself to mention even once unless bidden by an attorney.

The jury had seen an edited, 90-minute video of how Nicole Quintieri, the Flagler County Sheriff’s detective who was as solicitous as she was sharp in her 12-hour interview with him, giving him every chance to come clean and explain what truly happened the morning of April 7, 2018, on Palm Coast’s Felter Lane. Several times, by different means both Quintieri and George Hristakopoulos, who knew he was lying, tried to give him a way to be more truthful.

“Is there anything else that you can think of that you think is important for our investigation?” Quintieri asked him.

“As far as?” he asked, as if put out.

“As far as getting justice for your wife,” Quintieri said, framing it in terms she thought would resonate with Johansen.

“Better gun control in schools. Better gun control at schools. Readily available,” he replied after a five-second pause.

“What in the world does that have to do with this?” Quintieri asked.

“No, because if she knew better gun control, you know, it probably wouldn’t have happened,” he said.

Because blaming his wife for mishandling a gun and killing herself while her 6-year-old boy was watching TV in his room could not possibly tarnish her name.

Johansen in the three-and-a-half history of this case had also previously claimed Brandi had killed herself, though she was shot twice. He’d claimed an intruder could have come in and shot her. He’d even tried to pin the murder on Brandi’s 6 year old, the boy who called Johansen “daddy,” and who Johansen claimed he treated as his son.

As Johansen testified today, his tone direct, deadpan, his only emotions an occasional chuckle (though not nearly as many chuckles as during his interview with detectives the night of the shooting), there was never a hint of devastation, regret, sorrow, never a sense that he felt a loss, or that the loss had affected him in any way. He never uttered the word “love.” He never referred to Brandi’s son, whom he left orphaned, except to shrug off the time when he tried to blame him. His attorney, Garry Wood, might have elicited some emotion from him, asking him about Brandi more personally. Wood didn’t try.

Not that the trial day lacked for heart-rending moments–reminders to Johansen, which he saw just as the jury saw–whatever the context. In this, the prosecution’s last day before it rested, Assistant State Attorney Jennifer Dunton had shown the jury the series of interior-surveillance video clips intended to show Johansen at his worst. Those were the clips the defense tried to keep out of the jury’s view, arguing–accurately–that they showed Johansen in a bad light. Those were the clips from the five-hour ordeal on the night of April 5, when Johansen relentlessly dehumanized his wife, though the jury did not see him at some of his vilest, as when he joined racism to misogyny and accused his wife of making a “black baby.”

What the jury did see, however, was one clip from the morning of April 7, minutes before Johansen shot and killed Brandi. The surveillance camera Johansen had moved from the bedroom and placed in the kitchen shows Brandi’s last moments alive, if–with dismally unintended irony–headless: the camera frame caught her as she stood at the kitchen counter or a table, from the neck down to her waist, wearing the striped shirt that was shown the jury on Tuesday, her dried blood one of her last memorials.

Brandi is drinking coffee or something from a mug, and she is having a moment with her son. Johansen and his attorney had portrayed Brandi as hopped up on meth that day after 10 to 12 days of binging on meth, without sleep, as hallucinating, as out of control. The medical examiner on Tuesday had discredited the claim, citing levels of amphetamine and methamphetamine in her blood nowhere near levels that would cause irrational behavior. The serenity and affection she exhibits with her son in the video seemed to corroborate in more relatable terms what the medical examiner had said in clinical terms. She is telling her son about going to the fair later that day. Brandi and her sister had just made plans by messenger. The boy sounds excited, though what he says isn’t clearly audible. Mother and son are speaking in hushed tones, those tones when mere sound or inflexion is enough to convey a universe of emotions known only to mother and son.

A minute later in a separate clip, the boy appears almost in full in the frame. He is little enough for the frame to catch him. He is shirtless, he’s playing with an oversize towel or something like it. He says just a few words to his mother: “I love you. I do.” She says she loves him.

Johansen killed Brandi, in “self-defense,” minutes later.

It was the third time the jury had seen that striped shirt, the first time on Brandi while she was alive. Earlier in the trial Assistant State Attorney Jason Lewis, who is prosecuting the case with Dunton, posted on the courtroom’s three oversized television screens, and the smaller ones in the jury box, a picture of Brandi on the medical examiner’s table, just as she’d arrived there–her hands wrapped in paper bags, to preserve evidence, her bloodied shirt still on her, her eyes closed, the color and life in her face gone. Lewis was questioning the medical examiner. He didn’t have to leave the picture there. The medical examiner had explained its relevance. But Lewis, a savvy tactician, left it there anyway. He wanted the jury to take in the shock, to remember the look of a life violently ended at 25. Knowing that the jury would eventually see that video of Brandi alive in her last moments, he likely wanted the jury to make the association between the two images.

“Alright, is there any chance at all that something different happened? That you have not told us?” Quintieri had asked again in her long interview with Johansen.

“No, ‘cause, that’s what happened,” he told her, when he was still claiming he had nothing to do with the shooting, when he was still claiming he was in the shower and heard a pop, “like a balloon,” he’d said. “You guys are investigators. That’s what I seen. That’s what I heard.”

“I don’t want to add to the trauma that you’ve already gone through. I really don’t know,” the detective told him. “You can make it easier for yourself. We cannot. But this is your opportunity to help yourself. And to lay it all out for us.”

“If you’ve tried to pin something on me, why would I call 911?” he said.

“You have a conscience. That’s why,” Quintieri told him. “You love your wife. That’s why. Shit happens in the heat of the moment. You’re not a bad person. You’re not a fucking monster.”

“I would never do anything like that,” he said. “I can’t tell you something that I don’t know. I’m not going to make up something.”

But he’d done nothing but. Even he acknowledged he’d done little more than fabricate. Wood, Johansen’s attorney, had concluded his direct examination of his client with the standard questions allowing him ostensibly to exonerate himself.

“Let’s focus on the 7th, the day of the shooting. Did you have any plans in the morning when you got up to shoot and kill your wife?” Wood asked him.

“Definitely not,” Johansen said. He chuckled his answer, grinning.

“Had you been planning at any time prior to that occasion, at any time, to kill your wife that day?”

“No, sir. No.” This time Johansen didn’t chuckle. He didn’t grin.

“I have no further questions,” Wood said.

When the defendant takes the stand, rules demand that the prosecution gets a go at the defendant as indiscriminately as at any witness. That’s why defense attorneys generally discourage their client from testifying. It’s why Wood explained to Circuit Judge Chris France–out of the jury’s hearing–that he explained the pitfalls of testifying to Johansen. Johansen insisted. It is ultimately the defendant’s right, no matter what the attorney says. More so defendants who don’t trust their attorney, or have a higher opinion of their wiles than more ordinary persons. The judge has no say in the matter, unless the defendant is incompetent. (That possibility was briefly raised in Johansen’s case, early in pre-trial proceedings, and dismissed).

This afternoon, before the jury of 13, including an alternate (a 14th was dismissed after falling asleep on Tuesday), Dunton spent 39 minutes reminding Johansen of every lie he told, every story he made up, every fabrication he conjured to avoid saying what he was now willing to say on the stand, before the jury, a courtroom audience, Brandi’s family, and a national television audience (the trial is being reported and broadcast gavel to gavel by CourtTV).

He told Dunton he was charged with murder, which he hadn’t committed. “I didn’t murder nobody and that’s what I was charged with. That’s what I was referencing to,” he said, by way of explaining why he’d lied. But he was lying again, in front of the jury: when he was interviewed by detectives the night after the killing, when he spoke to his parents, he had not been charged. He wouldn’t be charged for more than two weeks yet.

“Mr. Johansen, since you’ve been arrested in this case and pending trial,” Dunton told him, “the whole time both the day of, and in the days early in the jail, not only as law enforcement told you the situation doesn’t make sense, but your parents told you your story doesn’t make sense. So you’re here now today to tell a story that matches the evidence and ask them to believe that now you’re telling the truth.” Dunton pointed to the jury.

“That’s because I am,” Johansen said.

“Even though you’re a liar.”

“That’s your opinion,” Johansen said.

“You lie for 12 hours to law enforcement,” Dunton continued.

“I told you I did,” he said.

“For 20 days.”

“If that’s what you say.”

“And today you’re telling the truth,” Dunton said.

“Correct,” Johansen said.

“No further questions.”

The attorneys are expected to present closing arguments Thursday and turn the case over to the jury in Courtroom 401 at the Flagler County courthouse.

![]()

Corn and Taters says

When did Quinteri come out of the jail and become a detective? That’s funny. She did always seem to have power envy. At least it seems they’ve put together enough to convict this guy. I do hope they have followed up with the child to make sure he’s getting services and counseling to lessen his PTSD.

FlaglerLive says

Becky Quintieri is the administrator at the jail. Nicole Quintieri Thomas is the detective, now with the State Attorney’s office.

Ray W. says

Becky Quintieri is one of those people whose hard work and excellence in maneuvering through many complex problems refutes anyone’s claim that government cannot accomplish anything. I have always found her to be helpful and knowledgeable, and pleasant, too. Flagler County citizens are lucky she chose to serve them. Her 20(+) years helping inmates with mental health issues and dealing with limited resources makes her one of the more resilient people I know. Thank you, Mrs. Quintieri.

Corn and Taters is attempting to stain the reputation of one of the best around. I know better.

Corn and taters says

I have concrete facts I could state if I wanted to give you a picture of who she is. I merely commented that she was previously jail staff and made the jump to Patrol which FlaglerLive corrected me on.

Mark Woods says

That kid is a joke with no punch line.

C’mon man says

This dudes guilty AF

Me says

GUILTY. LOCK HIM UP.

Trailer Bob says

Unfortunately, Meth kills in more ways than one…

This guy has to be removed from society for a long, long time.

Prays for the child involved.

Mark says

He does not have the mental capacity to stand trial. I hope someone checks his mental health

Just Wondering says

Does anybody know what type “Name” of the Berreta that was jammed??

Shelagh Oosthuizen says

Ray W : That’s awesome dude, love the way you stand up for another, that shows so much more integrity than talking cr@p about someone, 😉

Neighbor lady says

Corn and Tater tot : Is “power envy” is the only reason a woman might make a career move? You know you got corrected on who’s who, but I doubt you’ll learn about misogyny, character analysis or simple respectfulness today / this lifetime.