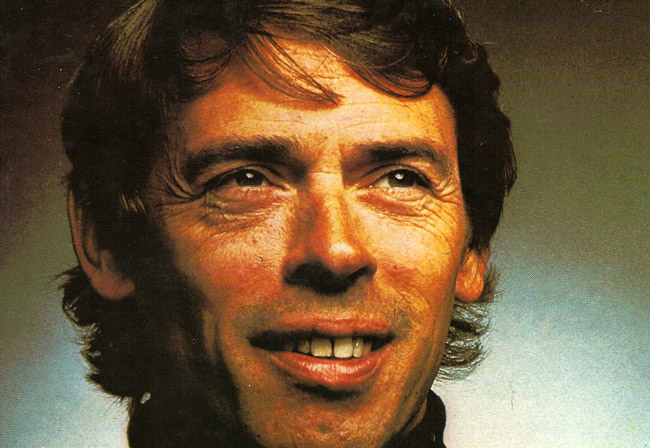

What is that exactly, and who is that, may be two somewhat legitimate questions to ask when confronted with the latest offering from Palm Coast’s own City Repertory Theatre, opening Friday: “Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris.” Particularly since Brel has been dead, in the least interesting sense anyway, for almost 34 years. But his fame and influence on music by the time he was just 38 was such, on both sides of the Atlantic, that the musical revue named after him premiered off-Broadway in 1968, a year after he announced that he would no longer be touring. The revue ran for four years and through many subsequent revivals, taking on more poignancy after Brel’s untimely death from lung cancer when he was 49. The question remains: who was this guy?

Brel’s name may not evoke much reaction these days, at least not in the United States. But when the Belgian-born singer and songwriter died in October 1978, his death had the same seismic feel in Europe as Elvis’s had had in the United States a year earlier, with a few differences. No one would ever accuse Elvis of having been a poet, a philosopher, a social conscience, a biting intimate of the human heart, a redemptive cynic, let alone someone who wrote all his own material. Brel was all that and more.

“There are many people who write love songs,” says John Sbordone, who is directing the production at City Repertory, the third full production of the season at Palm Coast’s newest (and most dynamic) stage. “His love songs have a depth and a perception about the anguish of love and the pure joy of it, that are exceptional. Very different. I would say—I don’t know if it means anything to anybody—that his existential view of life, that we are making it up, making our own morality as we go along, has a lot to do with what appeals to me about it.”

The production brings together a couple of dozen Brel songs, in English. The translations are unfortunately uneven, but that’s not the local production’s fault: it’s the work of Eric Blau and Mort Schuman, the original creators of the revue. The songs are arranged in a plotless order that reflects the eclecticism of Brel’s themes, though virtually every song is a plot onto its own (and more than once the sort of plot where Brel’s characters go to die). “Madeleine” is a circus-tempo riff on a man’s anticipation of the date of his life (“she’s America to me”) who makes a habit of standing him up. It’s the story of the eternal schmuck who doesn’t necessarily ever learn so much as he always hopes. “Mathilde” reprises the theme but on a darker note: it’s the jilted man whose lover returns to taunt him once more. He resists, begs his mother to pray for him, his friends not to abandon him, only to abandon himself to Mathilde once more and spit on God (“Je crache au ciel encore une fois”). The song’s last image is a favorite audacity of Brel’s, though unfortunately sanitized in the English version as the meaningless “I’ve gone and crashed through heaven’s door.”

Sbordone’s production, choreographed by Diane Ellertsen, stars four actor-singers, all of whom have worked with Sbordone before on local stages, either at the Repertory Theatre or at the Flagler Playhouse: Kelly Nelson (head of theatre at Flagler Palm Coast High School and star of “Hairspray”), Laniece Wilson (“Hairspray” and “Jesus Christ Superstar”), Brett Cunningham (a teacher at Imagine who also starred in “Hairspray” and “Superstar”) and Manny DaMata (“Cabaret” and “Last of the Red Hot Lovers”). They’ll be accompanied by keyboard, bass guitar, accordion, kazoos and triangles, and in a Sbordone invention for the show, poems (E.E. Cummings, Ginsburg, Angelou) will provide transitions for most of the songs.

Audiences, Sbordone said, “are going to laugh, they’re going to cry, they’re going to feel uplifted as well as they’re going to feel that the weight of the world is very heavy. So they’re going to go through a panoply of emotional experiences that they don’t often get in the theater.”

Brel can be unforgiving: to materialists, to presumption, to power, and especially to anything bourgeois, a term Americans prefer to think doesn’t apply to them, though he begged to differ in his last interview on American soil: “The bourgeois,” he said, “are more bourgeois here. I think the fools are more foolish, the wise ones wiser here than in Paris.” (“The bourgeois are like pigs,” goes the refrain of one of his most famous songs. “The older they get, the more stupid they become.”) In one line, Brel speaking to that interviewer had grasped the essence of the American paradox. His lyrics could do the same for lost love, old age, unfaithfulness, solitude, poverty, hope, death, childhood, or the landscapes of his imagination: Paris, the flatlands of Belgium, the hell of suburbs.

“When I sing I have power,” Brel said in the late 1960s, about the time when he decided to give up the stage. “When a man has power, he’s dead because he doesn’t know fear. If one doesn’t have fear he doesn’t live. I mean noble fear, not false fear. In two centuries, there will be no black people or white people, Jews or gentiles, only the timid and the others. One is honest only when one is afraid. A man isn’t worth anything if he’s immobile.”

The Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko saw Brel in Paris in 1963, the singer’s breakout year, and summed him up this way: “One moment Brel makes fun using sadness as a weapon, the next moment he uses scorn, then he shows a timid smile and that smile soon breaks into an infectious burst of laughter. When Brel laughs, it seems to me that he is only a hair’s breath away from sobbing.”

Two years later Brel made his American debut at Carnegie Hall, leaving his audiences “limp and in awe of his extraordinary ability,” in the words of Robert Alden, the Times reporter who’d seen him rise through the “depressing nightclubs of Paris to the music halls of Europe,” and who understood the man who’d become the biggest-selling singer in French of the 20th century: “Mr. Brel does not preach in his songs. He lives them. He becomes the bitter sailor drinking in the port of Amsterdam, the old person who is waiting for death, the timid suitor, even the bull dying under a hot Spanish sun so that an Englishman can pretend for a moment that he is Wellington.”

So the songs, even in translation and without Brel’s charismatic presence (he was known as a mesmerizing performer) still have power, especially in more intimate settings such as the Repertory Theatre’s small venue at Hollingsworth Gallery. “The rapport is not with the public, it is with people,” Brel had said of his own idea of performing. “The public is a false notion. The rapport one has with the public is a monologue. With people there is a dialogue. Besides, the writing, the idea, is the most important thing. Faulkner never sang.”

The quote pleased Sbordone: it’s inherent to his understanding of audiences and the directions he gives his actors.

![]()

“Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living iN Paris” will be staged at the City Repertory Theatre at Hollingsworth Gallery (at City Market Place, 160 Cypress Point Parkway, behind Walmart, in Palm Coast), on Jan. 20 and 21 at 7:30 pm, and Sunday, Jan. 22, at 2 p.m., and again Jan. 26 and 27 at 7:30 pm, and Jan. 28 at 2 p.m. Tickets are $15.00.

Brel: Amsterdam

An Interview With Jacques Brel

Leave a Reply