Last Updated: 1:58 p.m.

With Election Day four days away, Circuit Judge Chris France today said he will rule before Tuesday evening after hearing arguments in a citizen’s challenge of a controversial ballot proposal that would remove borrowing limits on Palm Coast.

France will decide whether the referendum Palm Coast voters are casting ballots on will be counted or not. The citizen’s challenge wants the measure nullified. The city wants it counted. The challenge, filed against the city by Alan Lowe, a former candidate for mayor, is the most consequential court case related to the ongoing election in Flagler County. It is the only such case in the county, ever.

Whether the referendum succeeds or fails won’t necessarily make France’s decision moot: either side could appeal, since there have been cases in Florida where such referendums have been invalidated even after the vote was counted and certified. But a failed referendum makes it less likely that either side would appeal.

France will not take a chance either way. He is not concerned about whether it passes or fails, if he were even to clear the way for it. He wants his order to withstand an appeal.

Assistant County Attorney Sean Moylan, who was in court representing Supervisor of Elections Keiti Lenhart–a named party in the suit; she was present–had only one request of the judge: “If you are inclined to remove the measure, that you would do so before 7 p.m. on election day,” Moylan said. The polls close at 7 p.m., and results begin to be published.

“I do understand that, and that’s well taken,” France said. He had established with the attorneys on all sides at the beginning of the 43-minute hearing that the arguments should “get into the heart of the matter,” in his words–the merits of the question, not procedural issues. (Palm Coast government just before 2 p.m. today issued a release to media that the judge had ruled to nullify the count. The judge had not ruled, and the city recalled its release shortly afterward. It appears that a proposed order by the plaintiff’s side had been mistaken as the actual order.)

Almost 60 percent of registered voters had already cast their ballot by the time France heard arguments in the case in late morning today, with a turnout of around 80 percent expected by election’s end.

Here’s the heart of the matter: In July the Palm Coast City Council approved the summary language for a referendum asking voters whether they would approve removing borrowing and leasing limits imposed by the city charter on the city council. The relevant provision of the charter reads: “Unless authorized by the electors of the City at a duly held referendum election, the Council shall not enter into lease purchase contracts or any other unfunded multiyear contracts, the repayment of which: extends in excess of 36 months; or exceeds $15,000,000.00.”

A majority of the council wanted that language eliminated. It could only do so by winning approval from voters at the November election, through a referendum. The council’s crafted this language for the ballot: “Shall Article VI of the charter be amended by removing provision 3 (e) related to fiscal contracting authority that limit the city’s ability to enter into public private partnerships, respond to emergencies and have the ability to address growth by having future residents contribute to infrastructure costs.”

Nowhere in the ballot question does the summary explicitly tell voters that they will lose a right currently afforded them, or what limit the city will no longer have to abide by. Instead, the language makes reference to the charter section, where it notes that it would be removing provision 3(e).

Lowe sued, arguing that the language is deceptive and contrary to the law’s requirement that it be “unambiguous.” The city has argued that ballot summaries aren’t perfect, that this language made explicit reference to the charter section to be removed, and that countering or nullifying an election would be an extraordinary step.

Lowe faces an “extraordinary legal burden” to make his case–to show the ballot summary is “clearly and conclusively defective,” Rachael Crews, the GrayRobinson attorney representing the city, argued to France. It is an “exceedingly high standard” because “you’re about to take the vote away from the people, and courts do not like to do that.”

Alex Nunchuck of the St. Johns Law Group argued the case for Lowe (who, curiously, but perhaps not surprisingly, was not in the courtroom: he has been more of a stand-in), with Douglas Burnett at his side and Jay Livingston of Livingston and Sword, the Palm Coast law firm, as co-counsel by phone. Crews argued the case for the city with Eliza Sweeney (“recently admitted to the Bar,” Crews said) at her side.

“I agree your honor, had the city not referenced 3(e), there would be a problem,” Rachael Crews of GrayRobinson, the firm representing palm Coast in the matter, said today. “There would be a problem here. We wouldn’t be able to, I think, survive a challenge. But the city did what they were supposed to do.”

Here’s the irony: it was Council member Ed Danko–who has staunchly opposed the referendum and sought to recruit a plaintiff to run this lawsuit–with Council member Theresa Pontieri, who at a July 3 meeting agreed to rewrite the amendment’s original version specifically to include that reference to 3(e). In other words, it was Danko (with Pontieri) who effectively closed the door to the challenge he would later champion, assuming France rules the city’s way.

Nunchuck said the mere addition of the charter provision, by reference, is insufficient (and in fact at the same July 3 council meeting, Council member Nick Klufas–who supports the referendum–ridiculed the idea that the “3(e)” reference would mean anything to voters: “Who would know provision 3, though,” he asked.)

“What we have here is there’s a reference of Article Six, section, 3(e),” Nunchack argued before France, but the reference is vague and unrelated to the remaining language of the summary. “So the argument that simply by reference to external terms enables the voter to educate themselves is, one, incorrect and two, there is precedent from the Supreme Court that where there’s not consistent usage, or kind of a direct line saying this is what it’s about, would render it defective” under state law.

Crews conceded that the referendum language was not perfect, but “perfection is not the standard,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be a model of clarity, and even if it could have been more artfully worded, that’s not the standard.” She noted that under law, “it’s not the function of the ballot question to educate the voters,” who is expected to have educated himself or herself before entering the voting booth. References included in the summary language, including the reference to 3(e), are “get out of free cards,” Crews said.

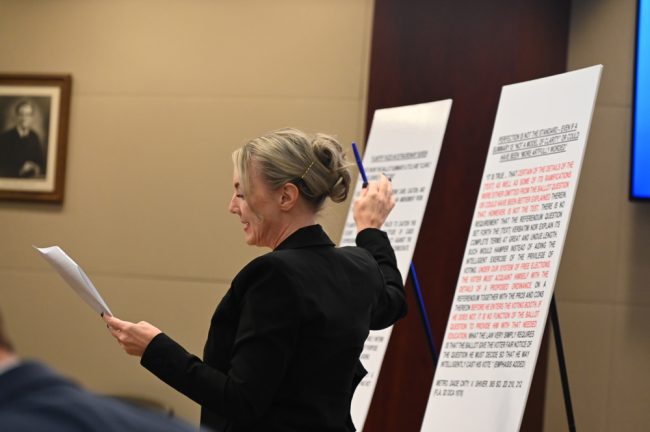

Crews used a series of poster boards, much like a powerpoint presentation, to illustrate her points–excerpts of case law, examples of ballot language, legal standards, some of the material highlighted in red. Her presentation was more direct, more fluid, and less hesitant than Nunchuck’s. While that doesn’t necessarily mean her argument was right, it certainly appeared more commanding, if not better prepared. That was mordantly apparent when at one point she referred to a case to support a point she was making and was interrupted by Nunchuck: the case wasn’t included in her filed responses to the court, he said.

“I think it was your case, actually,” Crews responded, a briefly stunning moment for the plaintiff’s side.

France at no point tipped his hand. He asked only one question–to Nunchuck as he was responding to Crews’s arguments. “if the voter is not adequately informed as to the chief purpose” of a referendum, Nunchuck said, “then what they vote on is not appropriate, and it’s a nullity, as argued by the Florida Supreme Court, because they weren’t advised as to the full effect of what they’re voting on in the first place.”

“If it’s to advise on the full effect, why is there a 75-word limit?” France asked him.

Nunchuck flubbed the answer–not because he didn’t answer it, in a manner of speaking, but because instead of answering with the obvious–voting booths aren’t reading rooms, and ballot language may not have to be perfect, but the 75-word limit forces it to be as honest and transparent as possible–he got lost in instances where 75-word limits don’t apply (which has no relevance to Palm Coast’s case), used words like “extensive ramifications” and “extensive regulatory framework” and other weedy concept before finally and all too briefly making the only salient point: “There’s one chief purpose. There’s one main legal effect here, which is the termination of a citizen’s right to vote on unfunded multi-year contracts in excess of 36 months or $15 million.”

It was an ironic reversal of roles: Crews, arguing for the city’s vague, opaque and unquestionably (if not intentionally) sloppy ballot language came off as lucid and direct as a pop-up book. Nunchuck, arguing against that sloppiness and for transparency, argued as if enmeshed in mud.

France had no further questions. “I’ll take the matter under advisement,” he said, thanking both sides for the hundreds of pages of legal authorities they had filed in support of their cases. For all the uniqueness and engrossing nature of the case, however, the courtroom was empty but for the parties, or at least their attorneys, in the plaintiff’s case, since the plaintiff himself didn’t bother to show. The absence could not possibly go unremarked as the City Council continues to wonder who, really, is behind this lawsuits, whatever its merits.

![]()

Leave a Reply