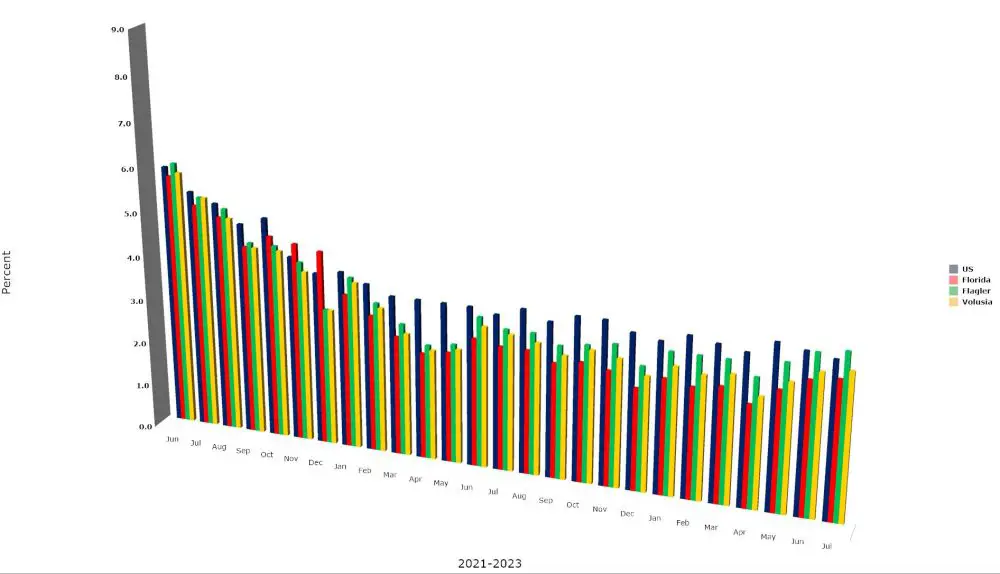

Flagler County’s unemployment rate in July was 3.7 percent, still very low by historical standards and still considered full employment by economist’s standards. But it was the highest rate in 18 months, going back to January 2022, when unemployment was at 4.1 percent.

The numbers may not be as indicative as they seem when other factors are taken into account: the county’s workforce has been surging, adding almost 3,000 workers in a year and topping 53,000 in July. The number of employed Flagler County residents hit another record in July, at 51,193, the fifth month this year that it has broken the previous record. To be considered employed, an individual has to record as little as one hour’s work in the given working period. The figures don’t differentiate between full and part-time work, or between voluntary poart0-timers and those who were unable to find full-time work–the under-employed.

New residents are flocking in–Palm Coast was the 18th-fastest growing city in the nation between 2020 and 2022, and is now past the 100,000 mark–but the job market’s rate of absorption may not be keeping up with as rapid an onslaught. Despite that, the number of people holding jobs grew by 2,422 in the past year, and by 217 in July. Comparatively, the number of people without jobs rose by more than 300 since the beginning of the year, reaching levels it hasn’t seen since January 2022, when 2,227 Flagler County residents were without jobs.

Employment number reflect the number of Flagler County residents with jobs anywhere in or out of the county, including telecommuters, whose ranks have also grown significantly.

As of last September, the last period for which the Bureau of Labor Statistics has figures, 27.5 percent of private-sector establishments had employees teleworking part or full time. The information industry, professional and business services, educational services and wholesale trade had the highest proportion of teleworkers (from 39 to 67 percent of workers).

In Florida, the unemployment rate went up to 2.7 percent after holding at 2.6 percent since the beginning of the year, in seasonally adjusted figures. (The unadjusted figures have the unemployment rate at 3.1 percent in July.) As in Flagler, the state’s labor force grow significantly–by 42,000 in July, adding 5,000 people to the unemployment rolls.

Some 295,000 Floridians are officially unemployed, but that figure is an undercount that only reflects the number of people the state counts as unemployed–the people who are following rigorous rules to be receiving unemployment checks, and the people who are receiving checks. After 12 weeks, they are cut off, and are no longer considered unemployed. Rather, they are considered individuals who have dropped out of the workforce. They have not, of course. Not in many cases, even though they are not actively looking for work. But that enables the state to keep its unemployment numbers low.

Additionally, independent contractors who now form a large and growing part of the economy–the gig economy–are not eligible for unemployment. So when they are out of work, they are not counted among the unemployed. That further artificially depresses the unemployment numbers.

So the official unemployment figure is deceptive, and is partially corrected by the federal government’s so-called U6 rate, or the “Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization,” which measures discouraged workers and those working part-time because they could not find full time work. The current U6 rate for Florida is 5.9 percent, a little below the national rate of 6.7 percent.

Yet another factor may be affecting the state’s unemployment. In a conference call with reporter, officials from the department that now calls itself the state Department of Commerce did not address the impacts of a new state immigration law that took effect July 1 or a rise in unemployment rates in rural counties in July. (The Department of Commerce used to be called the Department of Economic Opportunity, and before that it was the Agency of Workforce Innovation.)

The new law (SB 1718) includes changes such as requiring businesses with more than 25 employees to use the federal E-Verify system to check the immigration status of workers.

Agriculture Commissioner Wilton Simpson, a Republican who had defended the law as a way to help stem the tide of undocumented workers and drugs reaching Florida after crossing the Mexican border, recently said the law could have “unintended consequences” on the construction and leisure and hospitality industries.

Migrant workers and advocates have filed a federal lawsuit challenging part of the law that makes it a felony to transport into the state people who enter the country illegally. Among other things, the lawsuit alleges that part of the law is too vague.

Florida’s seasonally adjusted total nonagricultural employment was 9.77 million, an increase of 44,500 jobs over the month and 300,600 jobs over the year, an increase of 3.2 percent. Notably, this month’s release by the state’s labor department did not single out the private sector employment gains, as the DeSantis administration previously, insistently did, likely because government jobs increased by 1,700 over the month, including 1,400 in local government. The state’s job rolls include more than 1.1 million government jobs.

–FlaglerLive and the News Service of Florida

![]()

Palm Coast Resident says

Working people are also re-considering location due to the increased costs of housing. People working toward homeownership are priced out of the market, and renters are seeing increases beyond their income capacity. These factors may not the the sole reason we may start seeing unemployment rise, but they would certainly have an impact.