By Gregory Pierce

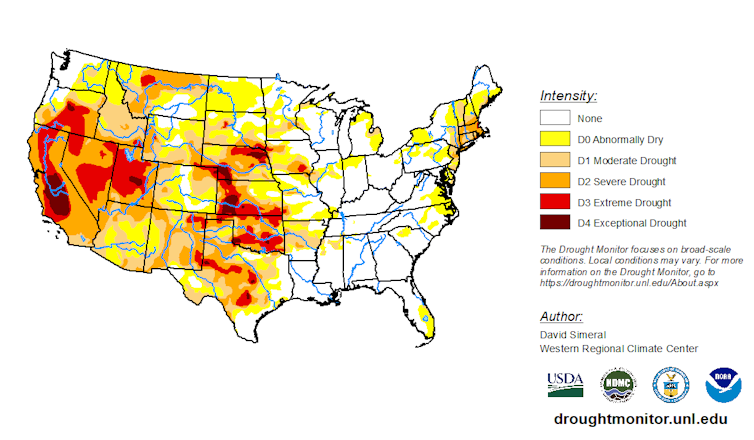

Coastal urban centers around the world are urgently looking for new, sustainable water sources as their local supplies become less reliable. In the U.S., the issue is especially pressing in California, which is coping with a record-setting, multidecadal drought.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom recently released a US$8 billion plan for coping with a shrinking water supply. Along with water conservation, storage and recycling, it includes desalination of more seawater.

Ocean desalination, which turns salt water into fresh, clean water, has an intuitive appeal as a water supply strategy for coastal cities. The raw supply of salt water is virtually unlimited and reliable.

Ocean desalination is already a major water source in Israel and the United Arab Emirates. Cities in the Middle East, Australia, Mediterranean Europe, the U.S. Southwest and Australia also rely on it. There are more than 20 ocean desalination plants operating in California, plus a few in Florida. Many more plants across the U.S. remove salt from brackish (salty) water sources such as groundwater inland, especially in Texas.

Nonetheless, current evidence shows that even in coastal cities, ocean desalination may not be the best or even among the best options to address water shortfalls. Here are the main issues that communities evaluating this option should consider.

Killing aquatic life

Scalable technologies for removing salt from water have improved steadily over the past few decades. This is especially true for treating brackish groundwater, which is less salty than seawater.

But desalination still can have major environmental impacts. Fish can be killed when they are trapped against screens that protect desalination plants’ intake valves, and small organisms such as bacteria and plankton can be sucked into the plants and killed when they pass through the treatment system. In May 2022, the California Coastal Commission unanimously rejected a proposed $1.4 billion ocean desalination plant in Huntington Beach, partly because of its potential effect on sea life.

Desalination plants discharge brine and wastewater, which can also kill nearby aquatic life if the process is not done properly. And generating the large quantity of energy that the plants consume has its own environmental impacts until it can be done carbon-free, which is still years off in most cases.

Unaffordable water from costly plants

Cost is another major hurdle. In most areas, the cost of ocean desalination is projected to remain considerably higher than the cost of feasible alternatives such as conservation for the next several decades – the timeline that utilities use when planning new investments. My colleagues and I found this in our research comparing water supply alternatives for Huntington Beach, even though we made favorable assumptions about ocean desalination costs.

Cost breakthroughs on major, market-ready technology in the near to medium term are unlikely. And desalination costs may increase in response to rising energy prices, which represent up to half the cost of removing salt from water.

Moreover, capital cost projections for desalination plants often greatly understate these facilities’ true cost. For example, the final cost ($1 billion) to build the ocean desalination plant in Carlsbad, California, which opened in late 2015, was four times higher than the original projection.

Our center has also explored whether piping in desalinated ocean water is a viable option for small, typically rural areas with public water systems or private wells that have run dry or are close to giving out. In diverse parts of California where this has happened, such as Porterville in the Central Valley and Montecito along the coast, the state is paying over $1 per gallon to truck in small supplies of bottled and vended water. That’s much higher than even the most expensive desalinated seawater.

U.S. Drought Monitor

In these cases, we have found that the relative economics and even the environmental impact may pencil out, but the politics and management of new pipelines do not. This is because water supply is typically governed locally, and many local areas beyond those benefiting would need to agree to a new pipeline from the coast.

More broadly, we find that proponents of these projects do not proactively pursue strategies that would make water access more equitable, such as designing utility rate structures that shield low-income households from higher costs, providing financial aid to small communities or consolidating water systems.

Better options: Conservation, reuse, storage and trading

In most places, several other supply options can and should be pursued in tandem before ocean desalination. All of these steps will provide more water at a lower cost.

The first and relatively cheapest way to address water shortages is by using less. Finding ways to get people to use less water could reduce existing demand by 30%-50% in many urban areas that have already begun conservation efforts.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Second, recycling or reusing treated wastewater is often less expensive than desalination. Technology and regulations in this area are advancing, and this is already making large investments in recycling possible in many arid regions.

Third, storage capacity for enhanced capture of stormwater – even in areas where it rains infrequently – can be doubled or quadrupled in regions like Los Angeles and parts of Australia, at one-third to one-half of the cost per unit of desalinated water.

Even cleaning up polluted local groundwater supplies and purchasing water from nearby agricultural users, although these are costly and politically difficult strategies, may be prudent to consider before ocean desalination.

The feasibility of desalination as a local supply option will hopefully change by midcentury as water scarcity problems mount because of climate change. For the medium term, however, ocean desalination is still likely to play a small role if it figures at all in holistic water strategies for coastal urban areas.

![]()

Gregory Pierce is Co-Director of the Luskin Center for Innovation, University of California, Los Angeles

Jimbo99 says

The one’s overpopulating the planet need to stop it. The solution is to close the borders and let the one’s that created their own problems somewhere else, solve their problems there, where they’re from. 2 different eras. Colonization of the 1492-1776 (284 years), it’s 2022 (246 years from Independence Day 1776), very little on this planet is left undiscovered. See there’s a big difference between those generations that colonized vs the freeloaders of today. Colonists went in search of undeveloped land to build a new life. These immigrants just want an instant better life where they go, just for showing up. It’s part of why I don’t relocate in America, it doesn’t matter where you go, you can’t run from yourself. The relocation is just a distraction for the time being and you end up with the same problems you had where you left when you relocate. Solve your own problems, not expect another to provide better for yourself. That goes for fresh water, nobody wants someone to develop upstream from them to pollute the water supply for anyone downstream.

Desalination is neither cheap nor easy, let’s make that clear and stop the madness & stupidity behind Biden-Harris solutions. We all see how crappy the Biden open border is working out. It’s exactly as I said it would go, the wealthier will never suffer or feel the open border growth. Martha’s Vineyard invasion, they deported those 50 immigrants. Other cities/towns don’t have that luxury. By the way, where did the 50 end up. All we see in the media was how awful it was they ended up in Martha’s Vineyard, where are they now is the question ? Besides, if it’s so awful in Martha’s Vineyard then why do the Obama’s live there ?

Michael Cocchiola says

Hmmm, Jimbob… are we a Qrumper? The subject of water drifted into the Green New Deal, Biden/Harris, anti-immigration, Martha’s Vinyard, and the Obamas. I thought I was at a Qrump rally.

Just something to think about… the Green New Deal proposal calls on the federal government to wean the United States from fossil fuels and curb planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions across the economy. It also aims to guarantee new high-paying jobs in clean energy industries.

So tell me, why is this bad?

Kerry, the climate Coo Coo says

Get rid of the GRASS on every lawn. Get rid of the GRASS on ALL Golf Courses, Use othe type of ground cover that does not need WATER.

Each home that has more then 2 bathrooms most pay 2 times the monthly cost of everyone else with only 2 bathrooms.

Rainwater barrels on every house . Maybe 2 or 3 depending on how big the house is.

Swimming pools most be used to catch rain water which is then used to flush toilets and wash dishes.

No more Water Parks

Ronjon says

The issue is the just about conserving, reusing, and storing water usage, it is how to get more water. As mentioned, the ocean is virtually unlimited and reliable. As far the environmental impact, the needs far outweighs the risk now. As for the cost, yes it is more expensive to produce and would cost consumers more. But that is if it is produce for a private for-profit company. If the government public utilities build and operates them, the cost would be lower to the consumer as as public utilities are not looking to make a profit. For them, the need outweighs the cost 9and profits). The ocean is there, it is time to tap in to it and take what we need to survive and thrive.