Maybe it was his preference for an empty courtroom. It’s easier to save face in the absence of an audience. Maybe it was just good sense breaking through a year’s intransigeance. “For what it’s worth,” the judge told Derrius Bauer this morning, “I think you made a wise decision.”

Two days after he stood before Circuit Judge Dawn Nichols to decline yet again to plead out and instead risk life in prison if convicted at trial, Bauer, 30, this morning signed a plea agreement that may have him out of prison by the time he’s 38.

Bauer pleaded no contest to accessory after the fact of a capital felony, a first degree felony. He had faced a first-degree capital murder charge, an attempted second degree murder charge, and a charge of firing into an occupied vehicle.

The lesser charge to which he pleaded would have been one of the so-called “lesser included offenses” that would have been part of a jury’s verdict sheet, giving it the option of convicting him on that charge instead of the capital charge. The family of Deon Jenkins had also agreed to the plea terms, having gotten satisfaction from the conviction of the shooter.

Bauer was sentenced to 15 years in prison. He has already served more than four at the county jail. He is eligible for gain time, or early release after serving 85 percent of his sentence. He could be out of prison by the time he’s 38.

Not just for Bauer but for the court, for prosecutors and for the Flagler County Sheriff’s detectives who cracked the case, the plea ends the oldest high-profile case on the docket, and the longest and most expensive investigation in the Sheriff’s Office’s history.

It also resolves what had been a puzzle for almost a year: why, after Marcus Chamblin, the man Bauer helped pull off the murder of Deon Jenkins, was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, Bauer continued to insist on his innocence and decline a generous plea his mother begged him in court, and in tears, to take. Assistant State Attorney Mark Johnson built his prosecution of Bauer on the same evidence that led a jury of 12 to convict Chamblin in 48 minutes.

This morning Wayne Henderson, Bauer’s attorney, told the court that his client had called him yesterday to say that he’d take the plea–to say he had no choice but to do so.

“I don’t ever want to take a plea when somebody says to me, they have no choice,” the judge told Bauer. “You always have the choice to go to trial. But I’ve explained to you my concerns about that and what your exposure is. So that’s one choice you have.” She said she would not prevent him from going to trial if that’s what he preferred. But she had also spent any a hearing trying to convince him not to.

“It sounds to me like you’ve been thinking about this, and you’re weighing what’s in your best interest to do, what’s the smart thing to do,” Nichols continued, laying out the alternative of a plea. “I can tell you that I think it’s a wise choice. I think it’s a smart choice. I think that you have thought about it very thoroughly and very carefully. And I think it’s the right choice, but ultimately it is your choice.”

Unemotionally, still mumbling his answers as he usually has, Bauer agreed. His attorney filled out the plea form. The judge went over it with Bauer, and sentenced him, ending the case. Bauer got fingerprinted and was ushered out. This time, his mother–who had walked out of the courtroom in sobs two days ago–was not there. Only three students attended the hearing, along with two of the three lead detectives who worked the case: George Hristakopoulos and Augustin Rodriguez. Darrell Butler was the third.

“We’re relieved that the case is finally completed,” Johnson said after the hearing. “This happened in 2019 so it’s been going on for about six years. We’re happy to see that some justice is finally served on both the defendants that were involved in this particularly egregious shooting that occurred in this particular community. It happened in such a way that really frightens people here in this community.”

It’s never been made clear what triggered Chamblin to kill Jenkins. Jenkins had been a roommate of Chamblin’s brother, D’Shawn Hosang. The night of Oct. 11, 2019, Hosang threw Jenkins out of the house and called Chamblin to complain about something regarding Jenkins–what that was remains a mystery. The most Hosang said when he testified was too petty to warrant even a dispute. He said there’d been some kind of disagreement over a pizza. That certainly was not what caused Chamblin to get enraged and arrange with Bauer to kill Jenkins.

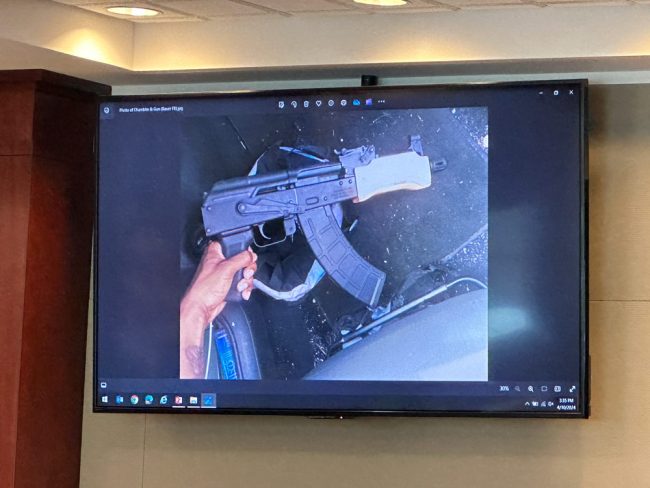

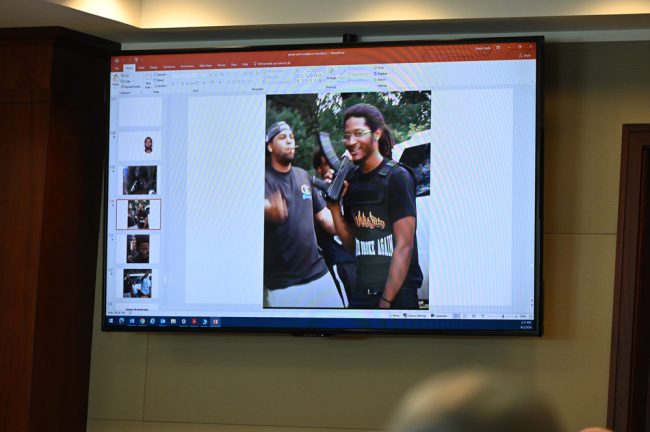

Bauer called Jenkins, drawing him to the Circle K on Palm Coast Parkway, where Bauer and Jenkins spoke. Bauer by then had dropped off Chamblin somewhere in neighboring weeds. After speaking with Jenkins, Bauer drove off. Chamblin walked through back alleys to the station, got behind Jenkins’s car, and fired his assault rifle, killing Jenkins and wounding a passenger, who survived. Bauer then picked up Chamblin and they returned to the Microtel, where they’d booked a couple of rooms.

Detectives used phone pinging data, texts, surveillance video and other evidence to reconstruct the hours and moments that led to the shooting, and the getaway afterward. It was difficult to imagine a different outcome for Bauer, had he gone to trial.

“It was a very good deal for him,” Johnson said. “It was an offer that we discussed with Deon Jenkins’s family, and they were on board with it. I think that once we tried Marcus Chamblin, who was the actual perpetrator of the shooting, actually killed their son, that was deeply satisfying to them, obviously this was satisfactory to them, so that’s what we went forward with.”

![]()

Purveyor of Truth says

Why cajole, browbeat and beg dangerous criminals to take a plea? Let them have their trial and send them away for life. Spare society the high likelihood he’ll reoffend and cause more misery.

Ray W, says

This is for Purveyor of Gullible Stupidity and any other gullibly stupid FlaglerLive commenter who thinks that we can take to trial every felony crime that is filed in the State of Florida by our legislatively limited number of prosecutors and public defenders. Every year, the legislature funds X number of prosecutors and X number of public defenders. Each position comes with a set amount of money for health care, life insurance, payroll, etc. The elected constitutional officers decide how to divvy up the money between their attorneys. Another chunk of money funds the staff, including the investigators and the secretarial assistants.

In October 1993, as a division chief in the state attorney’s office, I received a phone call from the chief detective of one of the cities assigned to my office. He told me I hadn’t been trying enough cases. I asked if he knew that I had tried more cases (22) through September that year than had any other felony prosecutor in the four counties of the circuit. He replied that he didn’t believe me, so I faxed him a copy of the circuit’s felony statistics through September. He soon called me back to tell me that his unit had read the report, and they had decided that I wasn’t trying enough of their cases. Gullible stupidity applies to detective sergeant’s, too.

Each year as a prosecutor, I received the annual statewide report on all of the felony statistics for prosecutors all around the state. Each year, prosecutors tried somewhere between 4% to 5% of all felony cases they had filed, regardless of circuit. Most defendants pled out. A significant percentage of the cases were dropped before trial each year.

From my circuit’s 1995 statistics, I closed over 500 felony cases in court that year, including VOPs. I handled another 150 or so cases that never made it to court (At that time, a prosecutor had to sign off on every traffic death investigation whether prosecution was warranted or not. This came to some 30 traffic deaths per year to my office, with a THI report averaging about 80 pages each. Sometimes, a single passenger accident claimed the driver’s life. No matter. The case had to be fully reviewed, and I had to approve every finding before I signed off that everything had been properly handled, because the report was to be sent to the federal agency that kept statistics on traffic deaths.). A 40-hour work week for 50 weeks per year meant that I had about three hours per case, on average, to investigate, prosecute and close the case. I worked many more hours per week than 40, but not every prosecutor was willing to do that. In order to get another secretary assigned to my office to help my other staff, I had agreed to do the intake on all of my cases. Every other office had at least one intake prosecutor who seldom went to court.

Over a 10-hour total spanning one full day and two hours of the next morning, the court to which I was assigned took pleas on 80 different cases.

You want every case to be tried, Purveyor of Gullible Stupidity? The legislature will have to authorize about 15 times the number of criminal trial judges to try all of the felony cases, complete with about 15 times the number of felony prosecutors and felony public defenders. That means new courthouses all over the state, more court clerks, more bailiffs, more judicial assistants, more staff in the attorney’s offices.

This is how it commonly works now. Two trial weeks per month per judge, usually with four prosecutors per judge. Time must be set aside for Arraignments, Pre-Trials, Docket Calls, hearing dates, and all the various other judicial duties such as violation of probation hearings. Of those 10 trial dates per month, at least two days are set aside for jury selection. Now, you are down to eight trial days per month. We have one circuit court judge trying felony cases in Flagler County. Sometimes, senior judges and backup judges can be found to handle more trials. If a typical felony trial judge handles around 1000 felony cases per year, including VOPs and VOCCs, just how is he or she going to be able to try them all in 96 trial days per year, not counting holidays off?

It is true that in 1995, I tried only four trials, but my shortest trial lasted five days, including jury selection. The longest, as I recall, lasted 12 days.

In the homicide unit, I had a death penalty trial with a week-long jury selection time, coupled with over two weeks of first phase evidence submission, plus another two weeks of second phase evidence submission. A newspaper reporter obtained the state’s total expenditures for conducting the near-six-week trial. It came to over $250,000 just to pay for the state’s costs external to normal office costs such as payroll, insurance, etc.

There are so many clueless FlaglerLive commenters who live in a fever-dream of impossibilities. Everything can be done in their idealized yet ignorant state, so long as they can imagine it. Purveyor of Gullible Stupidity is just another of these many clueless people. Get the legislature to allocate hundreds of millions of more dollars per year. Hire the judges and all the necessary personnel. Build the extra courthouses at $40 to $50 million per pop.

Just think. While some felons appeal their sentences after they plea out, most do not. Imagine how many of the tens of thousands of felony defendants, perhaps more than 100,000 per year, who will be going to trial, after which they will be appealing their trial convictions? How many more DCA courthouses would have to be built? How many appellate judges would be needed? Would we need a second Florida Supreme Court to handle the criminal trial appeals that reach the Supreme Court? Again, something along the line of 20% to 25% of all murder cases go to trial. If we tried all of them, we would need many more resources as homicides consume far more in time and resources than do any other type of crime.

I understand that the clueless among us are more than willing to consign other people to do the work their imagination demands. People like Purveyor of Gullible Stupidity is clearly not willing to do the work himself. And who knows if our legislature would be willing to raise the tax rate to finance this. Alaska tried in the 1970s, when all the oil money began filling the state’s coffers. When I was in law school in the early-80s, a professor talked of the Alaska experiment. Alaskans amended their constitution to require that every defendant either plea straight up as charged or go to trial as charged. About three years later, Alaskans repealed their amendment. Even when flush with oil money, it became burdensomely expensive to try everyone, so they stopped.

Purveyor of Truth says

Raymond,

You certainly inferred way too much from my comment. I’m quite aware that our criminal justice system has it’s limitations unless being used as lawfare, then no expense is spared. Anyway it’s still unbecoming for the court to beg criminals to plead. And I’m glad my post provided an opportunity for you to take a walk down memory lane and stroke your ego by sharing your alleged autobiography.

Wow says

Is the short sentence supposed to be good news?