Starting at midnight tonight, the Flagler County Courthouse will be a 24-hour operation, at least with regards to accessing records–felony court records, civil court records, traffic tickets, foreclosures, and so on. Not just the scant docket records that have been available for years, but the actual filings, such as arrest affidavits, civil complaints and the subsequent paper trail of each court case.

Lawyers, people representing themselves in court cases, interested members of the public and others who have been making the trip to the courthouse to access records will no longer have to do so. The records will either all be available at a click, or they’ll be able to electronically lodge a request for what records remain behind a protective wall, pending the necessary redactions.

“It gives people the right to view all documents that are not prohibited by court rule and law, which opens a window for them,” Clerk of Court Gail Wadsworth said. “The pro se filer has likely never had the capacity to turn on a computer and see what they’ve done and where their court case is, and after midnight tonight, they will.”

Flagler and all but two Florida counties–which are late getting their electronic systems in line, and have applied for extensions–are throwing the switch to provide the much broader access, in accordance with a Florida Supreme Court order issued in 2014. It is the culmination of an effort dating back to 2004 to have court records comply with the state’s open records law, facilitating access without compromising the sensitive nature of some of the information in court records. That includes private, redactable information such as date of birth, social security numbers, names of victims in domestic violence cases or sex crimes, or self-incriminating statements in arrest reports, prior to a case’s disposition in court.

The switch did not cost the clerk additional dollars: it’s covered as part of the annual, $54,000 the clerk pays its contractor, Pioneer Technology Group, for records maintenance.

The clerk is going through a 120-day pilot program (as are all clerks in the state), when domestic relations records will not be part of those accessible to the public. But much else will be. In most cases that pre-date mid-June, key records remain behind a level of protection that requires members of the pubic to submit an electronic request to view them. Once the request is lodged, the record goes into an electronic cue at the clerk’s office. Within four to 48 hours, the record is automatically redacted and any one of the office’s 19 clerks will ensure that the redaction complies with court rules. The record is then released for public viewing through the website.

“Right now we’re anticipating no more than 48 hours at its busiest,” Carlos Garcia, the clerk’s IT director, said Tuesday, referring to the turn-around between a request and a record being made available. “As long as we have enough clerks assigned to it we shouldn’t have any problem completing those requests in under four hours.”

Clerks are no longer doing the redacting by hand. Software does it. “Over the past two and a half three weeks we have been writing a business process or SOP for redaction so we won’t over-redact,” Wadsworth said, referring to the office’s standard operating procedures. “Because we don’t want to, and we don’t want to underedact either.”

The standards, viewable here, are precisely set out by state rules, not on an individual basis at the clerks’ office level.

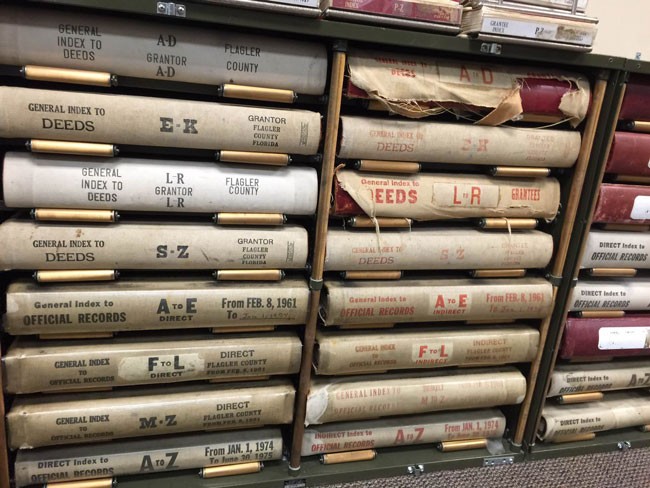

For the most part, there are no paper records anymore at the clerk’s office. Even when an arrest report comes in from the sheriff’s office, that record is scanned and the paper version is shredded. Two versions are produced: a redacted image, and a non-redacted image. Both are stored.

“We have local copies here, and then we have a disaster recovery site in Jacksonville at the federal reserve bank, a facility called Go-rack,” Garcia said. “That’s where we keep our backup copies, so we no longer back up to tapes. We do real-time backups to an offsite facility at a fairly secure place.”

The new system will reduce the use of clerks’ time considerably in one regard: they will no longer have to serve requests for paper records as tellers. Nor will the public have to pay for copies of records that are made available electronically. But the time saving at that end doesn’t necessarily mean that clerks will have more time on their hand, since they’ll be shifting attention to management of the electronic system.

But as far as the public is concerned, the new system is more convenient, less time-consuming, and less expensive.

“Online, not in line, that’s the whole premise,” Wadsworth said in an interview this afternoon in her office, repeating a line she highlighted in a news release earlier in the day.

groot says

It’s pretty neat. I noticed it this weekend. No secrets round these parts! Florida has a very broad public records policy and that is no exaggeration. I followed a few cases I know of and I noticed felony charges were dropped when victims declined to testify. It is a wealth of info.

ken says

Will you print the link(s) to these records? Thank you.

Gail Wadsworth says

Here you go…

http://www.flaglerclerk.com/courtrecords.htm