By Adam Izdebski, Alessia Masi and Timothy P. Newfield

In popular imagination, the Black Death is the most devastating pandemic to have ever hit Europe. Between 1346 and 1353, plague is believed to have reached nearly, if not every, corner of the continent, killing 30%-50% of the population. This account is based on texts and documents written by state or church officials and other literate witnesses.

But, as with all medieval sources, the geographical coverage of this documentation is uneven. While some countries, like Italy or England, can be studied in detail, only vague clues exist for others, like Poland. Unsurprisingly, researchers have worked to correct this imbalance and uncover different ways for working out the extent of the Black Death’s mortality.

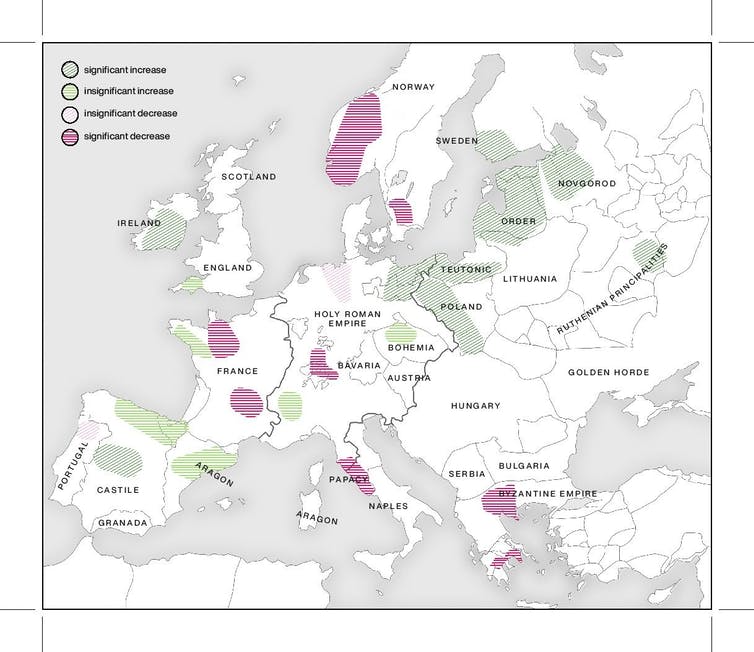

In our new study, we used 1,634 samples of fossil pollen from 261 lakes and wetlands in 19 European countries. This vast amount of material enabled us to compare the Black Death’s demographic impact across the continent. The result? The pandemic’s toll was not as universal as currently claimed, nor was it always catastrophic.

Natural archives

Lakes and wetlands are wonderful archives of nature. They continuously accumulate remains of living organisms, soil, rocks and dust. These (often “muddy”) deposits can record hundreds or thousands of years of environmental change. We can tap these archives by coring them and analysing samples taken from the cores at regular intervals, from the top (present) to the bottom (past).

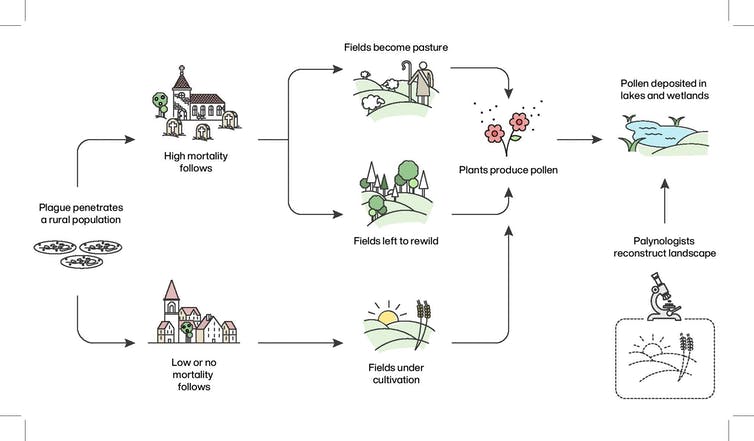

We relied on pollen analysis in our study. Because pollen grains are built of durable polymer and differ in shape between plants, they can be counted and identified in each sediment sample. These grains allow us to reconstruct the local landscape and changes over time. They shine a light on human land use and the history of agriculture.

For more than a century, paleoecologists – people who study past ecosystems – have been amassing data. In several world regions, the quantity of evidence available is overwhelming and certainly enough to ask questions about big historical events, like the Black Death. Did its mortality affect land use? Were arable fields turned into pasture or deserted and left to rewild?

If a third or half of Europe’s population died within a few years, one might expect a near collapse of the medieval cultivated landscape. By applying advanced statistical techniques to available pollen data, we tested this scenario, region by region.

Palaeoecology and past demography

The ecology of the Black Death

We discovered that there were indeed parts of Europe where the human landscape contracted dramatically after the Black Death arrived. This was the case, for instance, in southern Sweden, central Italy and Greece. In other regions, like Catalonia or Czechia, however, there was no discernible decrease in human pressure on the landscape. In others yet, such as Poland, the Baltic countries and central Spain, labour-intensive cultivation even increased, as colonisation and agricultural expansion continued uninterrupted throughout the late Middle Ages. This means the Black Death’s mortality was neither universal nor universally catastrophic. Had it been, sediment records of Europe’s landscape would say so.

Black Death’s demographic impact

This new narrative of a regionally variable Black Death fits well with what we know about how plague can spread to and between people, and how it can circulate in urban and wild rodents and their fleas. That plague did not equally devastate every European region should not surprise us. Not only will societies be affected and be able to respond differently, but we should not expect plague to always spread in the same way or for plague pandemics to be easily sustained.

Plague is a disease of wild rodents and their fleas. Humans are accidental hosts, who are generally thought to be incapable of long sustaining the disease. Although how plague outbreaks spill out of wild rodent reservoirs and spread to and within human populations is a subject of ongoing study, in human societies we know it can spread via several means.

People may most often contract it through flea bites, but once successful spillovers occur, multiple means of transmission can play a role, and so human behaviour, as well as living conditions, lifestyle and the local environment, will affect plague’s capacity to disseminate.

While plague transmission in the Black Death remains to be untangled, historians have tended to focus on rats and their fleas since the early 20th century, and to expect plague to have behaved in the Black Death in very similar ways in many places.

But as scholars have rethought the pandemic’s map and timeline, we must also rethink how it spread. Local conditions would have influenced plague’s diffusion through a region and thereby its mortality and effect on the landscape.

How people lived – 75%-90% of Europeans lived in the countryside – or how much, how far and by what means they moved around, could have influenced the pandemic’s course. Patterns of grain trade, which would have helped rats get around, could have been another important factor, as could have been weather and climate when the plague began.

p

Victims’ health and regional disease burdens were yet other variables, two also partially shaped by weather, not to mention nutrition and diet, including the sheer availability of food and how it was distributed.

Pandemic lessons

Our discovery of stunning regional variability in the Black Death has consequences, potentially in and beyond the study of plague’s past. It should prevent us from making quick generalisations about the spread and impact of history’s most infamous pandemic.

It should also change how the Black Death is used as a model for other pandemics. It may still be the “mother of all pandemics”, but what we think the Black Death was is changing. Our discovery might also prevent us from drawing easy conclusions about other pandemics, notably those less studied and with narratives based on fragmentary evidence.

Context matters. Economic activity can determine routes of dissemination, population density can influence how quickly and widely a disease spreads, and pathogen “behaviour” can differ between climates and landscapes. Medical and popular theories about disease causation will shape human behaviour, as trust in authorities will affect their ability to manage disease spread, and social inequalities will ensure disparities in an outbreak’s toll.

While no two pandemics are the same, the study of the past can help us discover where to look for our own vulnerabilities and how to best prepare for future outbreaks. To begin to do that, though, we need to reassess past epidemics with all the evidence we can.

![]()

Adam Izdebski is Independent Max Planck research Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Alessia Masi is a

Researcher in Palaeobotany at Sapienza University of Rome. Timothy P. Newfield is Professor of Environmental History and Historical Epidemiology at Georgetown University.

Leave a Reply