By Shannon Gibson

When President Donald Trump announced in early 2025 that he was withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement for the second time, it triggered fears that the move would undermine global efforts to slow climate change and diminish America’s global influence.

A big question hung in the air: Who would step into the leadership vacuum?

I study the dynamics of global environmental politics, including through the United Nations climate negotiations. While it’s still too early to fully assess the long-term impact of the United States’ political shift when it comes to global cooperation on climate change, there are signs that a new set of leaders is rising to the occasion.

World responds to another US withdrawal

The U.S. first committed to the Paris Agreement in a joint announcement by President Barack Obama and China’s Xi Jinping in 2015. At the time, the U.S. agreed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2025 and pledged financial support to help developing countries adapt to climate risks and embrace renewable energy.

Some people praised the U.S. engagement, while others criticized the original commitment as too weak. Since then, the U.S. has cut emissions by 17.2% below 2005 levels – missing the goal, in part because its efforts have been stymied along the way.

Just two years after the landmark Paris Agreement, Trump stood in the Rose Garden in 2017 and announced he was withdrawing the U.S. from the treaty, citing concerns that jobs would be lost, that meeting the goals would be an economic burden, and that it wouldn’t be fair because China, the world’s largest emitter today, wasn’t projected to start reducing its emissions for several years.

Scientists and some politicians and business leaders were quick to criticize the decision, calling it “shortsighted” and “reckless.” Some feared that the Paris Agreement, signed by almost every country, would fall apart.

But it did not.

In the United States, businesses such as Apple, Google, Microsoft and Tesla made their own pledges to meet the Paris Agreement goals.

Hawaii passed legislation to become the first state to align with the agreement. A coalition of U.S. cities and states banded together to form the United States Climate Alliance to keep working to slow climate change.

Globally, leaders from Italy, Germany and France rebutted Trump’s assertion that the Paris Agreement could be renegotiated. Others from Japan, Canada, Australia and New Zealand doubled down on their own support of the global climate accord. In 2020, President Joe Biden brought the U.S. back into the agreement.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Now, with Trump pulling the U.S. out again – and taking steps to eliminate U.S. climate policies, boost fossil fuels and slow the growth of clean energy at home – other countries are stepping up.

On July 24, 2025, China and the European Union issued a joint statement vowing to strengthen their climate targets and meet them. They alluded to the U.S., referring to “the fluid and turbulent international situation today” in saying that “the major economies … must step up efforts to address climate change.”

In some respects, this is a strength of the Paris Agreement – it is a legally nonbinding agreement based on what each country decides to commit to. Its flexibility keeps it alive, as the withdrawal of a single member does not trigger immediate sanctions, nor does it render the actions of others obsolete.

The agreement survived the first U.S. withdrawal, and so far, all signs point to it surviving the second one.

Who’s filling the leadership vacuum

From what I’ve seen in international climate meetings and my team’s research, it appears that most countries are moving forward.

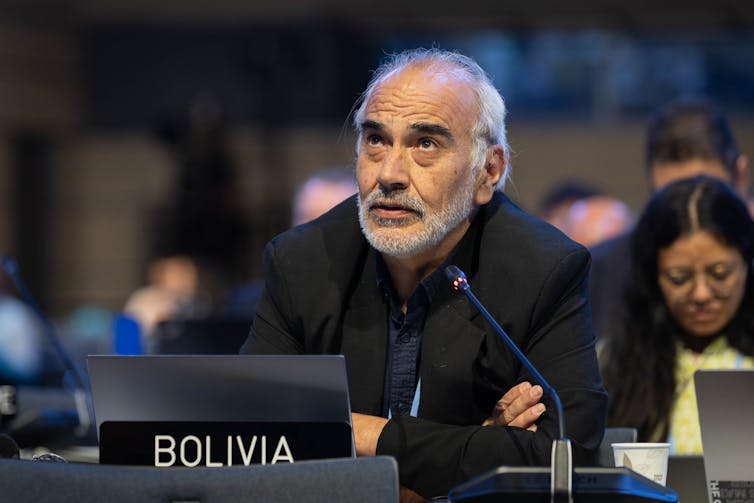

One bloc emerging as a powerful voice in negotiations is the Like-Minded Group of Developing Countries – a group of low- and middle-income countries that includes China, India, Bolivia and Venezuela. Driven by economic development concerns, these countries are pressuring the developed world to meet its commitments to both cut emissions and provide financial aid to poorer countries.

IISD/ENB | Kiara Worth

China, motivated by economic and political factors, seems to be happily filling the climate power vacuum created by the U.S. exit.

In 2017, China voiced disappointment over the first U.S. withdrawal. It maintained its climate commitments and pledged to contribute more in climate finance to other developing countries than the U.S. had committed to – US$3.1 billion compared with $3 billion.

This time around, China is using leadership on climate change in ways that fit its broader strategy of gaining influence and economic power by supporting economic growth and cooperation in developing countries. Through its Belt and Road Initiative, China has scaled up renewable energy exports and development in other countries, such as investing in solar power in Egypt and wind energy development in Ethiopia.

While China is still the world’s largest coal consumer, it has aggressively pursued investments in renewable energy at home, including solar, wind and electrification. In 2024, about half the renewable energy capacity built worldwide was in China.

Martin Bernetti/AFP via Getty Images

While it missed the deadline to submit its climate pledge due this year, China has a goal of peaking its emissions before 2030 and then dropping to net-zero emissions by 2060. It is continuing major investments in renewable energy, both for its own use and for export. The U.S. government, in contrast, is cutting its support for wind and solar power. China also just expanded its carbon market to encourage emissions cuts in the cement, steel and aluminum sectors.

The British government has also ratcheted up its climate commitments as it seeks to become a clean energy superpower. In 2025, it pledged to cut emissions 77% by 2035 compared with 1990 levels. Its new pledge is also more transparent and specific than in the past, with details on how specific sectors, such as power, transportation, construction and agriculture, will cut emissions. And it contains stronger commitments to provide funding to help developing countries grow more sustainably.

In terms of corporate leadership, while many American businesses are being quieter about their efforts, in order to avoid sparking the ire of the Trump administration, most appear to be continuing on a green path – despite the lack of federal support and diminished rules.

USA Today and Statista’s “America’s Climate Leader List” includes about 500 large companies that have reduced their carbon intensity – carbon emissions divided by revenue – by 3% from the previous year. The data shows that the list is growing, up from about 400 in 2023.

What to watch at the 2025 climate talks

The Paris Agreement isn’t going anywhere. Given the agreement’s design, with each country voluntarily setting its own goals, the U.S. never had the power to drive it into obsolescence.

The question is if developed and developing country leaders alike can navigate two pressing needs – economic growth and ecological sustainability – without compromising their leadership on climate change.

This year’s U.N. climate conference in Brazil, COP30, will show how countries intend to move forward and, importantly, who will lead the way.

![]()

Shannon Gibson is Professor of Environmental Studies, Political Science and International Relations at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. Research assistant Emerson Damiano, a recent graduate in environmental studies at USC, contributed to this article.

JimboXYZ says

When I 5ried to see the US contribution for the graph “Tracking annual carbon emissions over time”, I really did’t see the graph data points of the USA for it’s contribution ? I was able to see North America excluding USA. My point, what is the point of excluding the USA from that graphic while having a color code for USA ? And Oceania ? That’s Australia, New Zealand & other Pacific Islands.

“Who’s filling the leadership vacuum” ? The vacuum is just getting larger as the population grows, we have no leaders, just figureheads acting the role for the time they get in that position. They all need to be at the Emmys/Oscars. And I doubt any of them are going home with any trophy(ies) that night.

Deborah Coffey says

Yep. America FIRST means America ALONE means America LAST. The end.

Pogo says

@Professor Gibson

Well said. Trump is the Marlboro Man handing out samples at an oncology hospital.

Oh, well.

R.S. says

It’s kind of a delightful irony that MAGA is ratcheting up the climb of China and Brazil as world powers to lead the rest into a clean-energy future. Trump and MAGA were betting on revitalizing the past; kudos to the rest of world for working toward at a better future.

NJ says

The Pro- Chinese Communist Party Report FAILED to Report that China has DESTROY Coral Reefs in the South China Sea to build Island Military Bases.. The GOAL of the CCP is to Make China the Leader of the World by Making All Nations a Trade Colonies of China. Wake Up Americans, we are a NEW Cold War that was Started by China. China Supports Russian INVASION of Ukraine back purchasing Oil from Russia and Iran (who also Supports Russia). Americans must NOT forget the Japanese Military in the South China Sea just before 1941 when they Stupidly ATTACKED America! China’s Support of the World Control of Climate is just another part of “China First World Policy”!

Ed P says

-China’s carbon emissions are reported by a combination of Chinese government agencies who provide information to international agencies. Huh.

-30 percent of the worlds carbon emissions are China, their population accounts for about 17.7% of worlds. Huh.

-Little if any reductions by China have actually occurred. Huh.

-A resurgence in construction of new coal-fired power plants in China has hit the highest level in the past 10 years and undermining the country’s clean energy progress. Huh.

-China has a “goal” to reach emissions peak output by 2030. So it’s growing? Huh.

-US reduced it emission output with or without the Paris accord. Huh?

And China and others countries are disappoint in the United States. Rich

Laurel says

The world will work around us.