| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

Big, brutal, poetic, a hero among states, Alaska has always been America’s national park of the imagination, a 600,000-square-mile invention colonized by a few tracts of reality.

The name itself, “the great land” in Aleut, conjures with its sled of a’s an expanse that trails endlessly to nowhere — ALAs-kaaaa — as if the sounds between tongue and palate toll the beginning of a journey. It’s true: mine began weeks before I left Florida, with the word a whirl of anticipation in my head at night. An avenue three blocks away had never sounded more distant, or Anchorage so near.

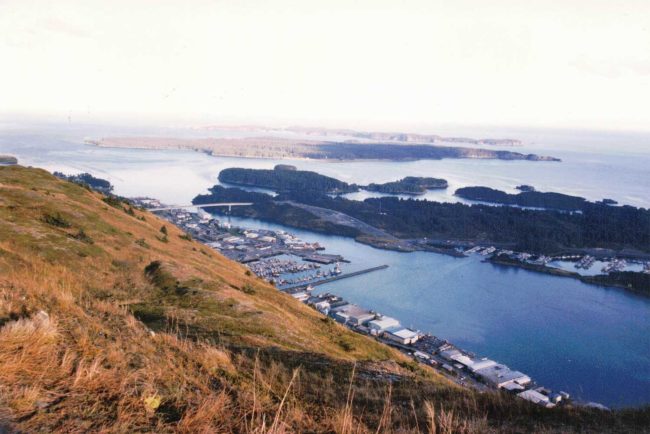

I had decided to drive the 5,200 miles to my destination — Kodiak Island — rather than fly in, because it made sense to cross the procession of states that had preceded Alaska’s so-recent entry into the union, from overdeveloped East to emptier West to a primitive Far North. I’d soon find that the primitive in Kodiak is a bit more imagined than real.

I’d left Florida late one afternoon in a September drizzle, with 12 days to make Homer, the tiny Alaskan fishing town hooked on quaint at the southern tip of the Kenai Peninsula. There, I’d catch the last outgoing ferry of the season to Kodiak, giving me a week on the largest island in the country after Hawaii.

It wasn’t until I was past the bumpy Appalachian afterthoughts of northwestern Georgia that the dimensions of the trip began to hit me: I was driving to Alaska. No offense to Delaware or Georgia, but it’s not like going anywhere in the Lower 48s, where simply being cocooned in the contiguous scales down anticipation. Red and Blue state conceits aside, there’s a sameness of safety and expectations to the 48s that doesn’t let up, a sameness Alaska defies as it ridicules ordinary human imaginations.

John Muir found himself “embosomed in scenery so hopelessly beyond description.” John McPhee described it as “a foreign country significantly populated by Americans,” but “where people are even more marginal than plants.” Merle Colby, who wrote the 1940 WPA Guide to the state, counterintuitively discouraged visits with the book’s opening line: “The best way to know Alaska is to spend a lifetime there.” Few do. The entire population of the state doesn’t exceed that of Polk County.

So what are lesser hacks to do with this outland where mere place names, says McPhee, “are so beautiful they run like fountains all day in the mind”? My mind’s gurgles pictured plenty of whiteness, ice, peak-riddled mountains jutting up from the beds of thick conifer forests, a lot of rivers moving fast, visions of salmon, because for homebodies schooled on nature television shows it’s impossible to think of southern Alaska without shoals of salmon rutting it upriver to spawn or land, kabob-like, on the fangs of bears. I pictured trawlers and crab-fishing boats crowding bays at the foot of rugged mountains and imagined great expanses of tundra, even though I had no idea that tundra meant “treeless heights,” that I would soon be grazing parts of the tundra or that it’s endangered.

I also pictured embarrassing stereotypes — Eskimos and igloos and log-house settlements disconnected from utility poles and combustion engines, although I knew that a) I was not going anywhere near places of the sort and b) those places don’t exist. The most remote settlement is a bush plane ride away. There are Eskimos on Kodiak, the original Aleut, or Alutiiq people, but they have cable TV, eat Chinese on Christmas and see therapists like everyone else.

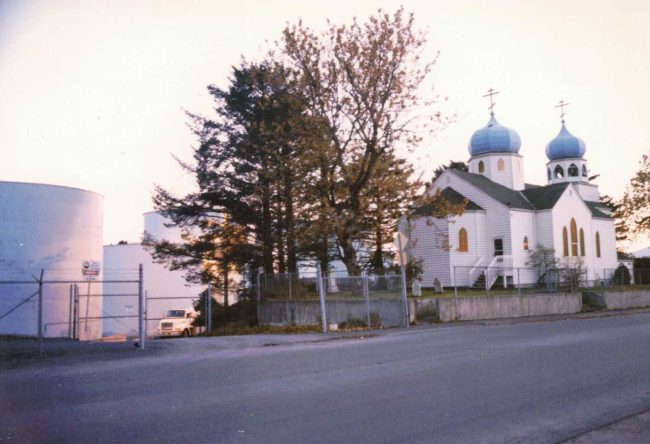

The most arresting human architecture on Kodiak is the Holy Resurrection Russian Orthodox Cathedral and its onion-shaped turquoise domes, testament to the island’s colonization by Russian fur traders at the end of the 18th century.

Photographs of the church’s latest incarnation–it’s been rebuilt four times–tend to crop out the scene a few feet south, the closest thing to igloos when glanced by satellite: 10 massive white fuel tankers. It’s the supersize version of Alaskan flora wherever one or more human beings gather for more than a few days: the 55-gallon drum, with a twist. Some of the tankers in the shadow of the church are imprinted in huge boldface with the letters: PMS, for Petro Marine Services, which greet you, along with the waves of Aleut children, as you sail by in the ferry. (PMS since my visit redesigned, spelling out the name in deference to its spiritual neighbor and its greener aspirations.)

So most of my prefab images crinkled the moment I stepped on the island. But traveling slowly to Alaska is as close as we get anymore to conjuring up the sort of El Dorado Old World travelers on their way to the New must have made up a century ago. Slow travel to strange, distant lands was once a necessity, dangerous and uncertain, more hopeful than reasonable. The utopian images on the other side provided the required courage to face “the promise and the menace of an escape from the past,” as Christopher Lasch put it.

That kind of travel is all contrivance now, a luxury reserved for the extreme few–the few extremists–who might afford the risk and expense of a trip to the 98 percent of Alaska’s untouched interiors. A hundred years ago they hunted elephant tusks in Central Africa and wrote stories like “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Today they troll for elite isolation while showing it off in every social medium imaginable. For everyone else there is no past that needs escaping, the present being as prosperous as ever. We plan our escapes into the wild on trails of simulated danger. Getting into harm’s way takes effort, or organized tours.

So when we call Alaska “the last frontier” — a title Alaska’s tourists take seriously — we can’t mean it the way we did when Ohio or Indiana or the Dakotas were the frontier, where cruelty and violence had as much to do with taming the wild country as did singing Amazing Grace after a hard day’s barn-raising. John Troy, the state’s governor in 1940, said as much in his introduction to the WPA guide when he cautioned readers “with vague schoolroom ideas of Alaska as a frozen land of ice and snow” that they may “find themselves deprived of many cherished illusions,” pretty much as I did did decades later.

*

Far from a frontier, Kodiak is an outpost of American tensions, “an island of ten thousand gray shades,” as David Allen Cates described it. Kodiak’s fisheries are still among the richest in a world of devastated fisheries. But for an island only a little bigger than my native Lebanon and a population about the size of the Flagler County school district (12,800 people), the density of conflict was everywhere — conflicts between big and small fishermen, between fishermen and government, conflicts within fisheries as overcapitalization and bankruptcies forced downsizing, conflicts and jealousies between the handful left of native Aleuts–who once numbered perhaps 20,000 before Russians landed–and whites, simmering conflicts between Filipinos, Hispanics, Asians and whites, conflicts between developers and environmentalists, and the overriding conflict between man and nature. The interchangeable parts of American conflict don’t change no matter where we go.

The first thing you see when you get off the ferry is a grim mass of gray docked like an iceberg of steel. I took it at first to be one of those warships stripped of guns and permanently anchored to tourism. It was actually a Tyson Foods fish processing plant formerly known as Star of Kodiak where, among other things, millions of tons of pollock became fishmeal or surimi, a sort of low-grade fish paste disguised as crab meat. It’s big in East Asia and in America’s fast-food fish sticks.

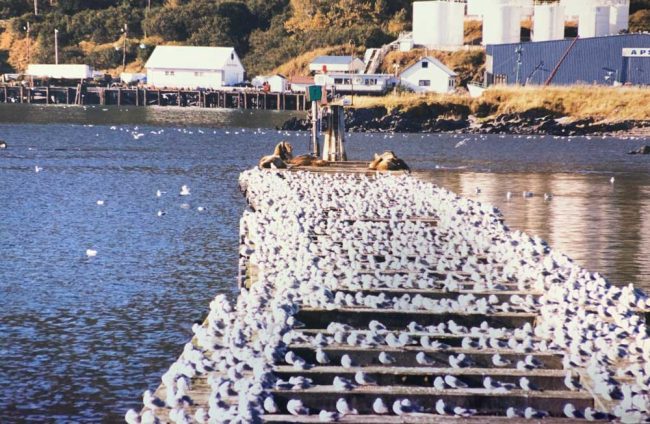

The second thing you see is the forest of masts and antennas rising out of the four hundred-odd fishing boats anchored in St. Paul Harbor and nearby St. Herman Harbor. The boats aren’t big — 30-, 40, 50-footers. Lolling in the protected waters with names like “Breezy Dee,” “Miss Heather,” “Suzanne,” “Ana Pilar,” “Risky Business,” they don’t look like the sort of vessels that can withstand the North Pacific’s storms, among the most violent on the planet. But they do. These aren’t gentlemen’s fishing hobbies. They’re business.

They are nothing compared to the big trawlers: Not visible anywhere near the island are the huge factory ships that harvest, process and package the sea’s bounty of pollock and other ground-fish without coming to port (or paying the taxes for fish landed on the island) for weeks at a time. Their massive nets can pull in fish by the ton, each haul a rake of the ocean bottom as ecologically considerate as strip-mining.

The processors, the independent fishing boats and the factory ships form the triad of the north Pacific’s multi-billion dollar fishing industry. They cannot all compete for the sea’s limited resource. What has happened in the rest of the world — $70 billion-worth of fish caught by an industry that cost $124 billion to run around the time when I visited; it’s become less sustainable since — has kept happening on a smaller scale in the north Pacific’s overcapitalized fisheries. That meant too many fishermen and not enough fish in the sea. Hardly a week goes by without dire revelations of disappearing species from crab to sharks to cod, tuna and rays.

To prevent overfishing off Kodiak, the third-largest fishing port in the country (by fishing volume brought to shore), the government instituted a quota system that tended to benefit big fishing operations at the expense of the small independent fishermen. At least that’s how the small independent fishermen saw it. Regulators argue that without a quota system the fisheries would have been overexploited faster than they were, though by then there was a third equation in play: climate change. None of this mattered to the consumer. Fish would keep making it to the dinner table at reasonable prices because there’d always be someone there to fish. The question was: Who?

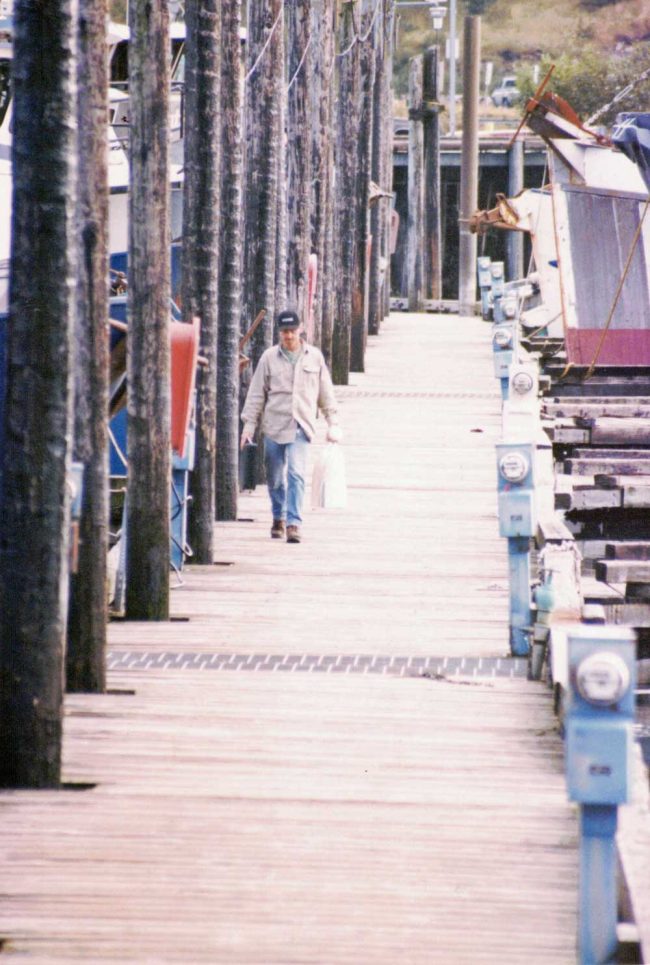

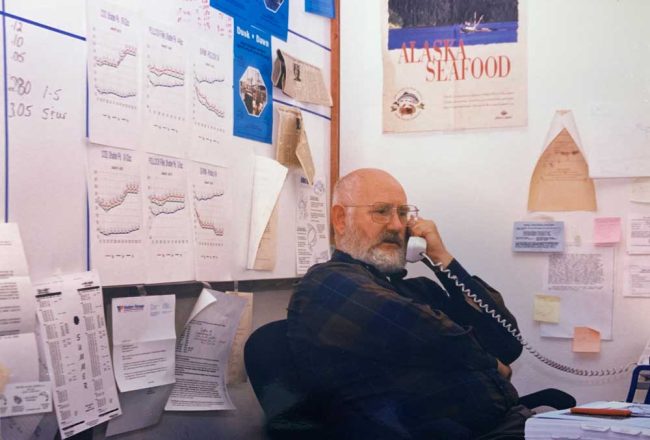

Walking away from it all out of disillusion–and eventually did. He now lives in California. (© FlaglerLive)

It wasn’t to be people like Andre Nault anymore. The 46-year-old Montana native had been fishing in Kodiak for 28 years when I met him. He was one of about 1,500 independent, commercial fishermen that have given Kodiak its radiance of individualism. Few of them natives of the island, fishermen like Nault arrived here in the 1970s and 80s convinced that unbridled work meant unbridled success. It was to them all bridled now — by quotas, regulations, hyper-competition, and also by an American palate that won’t eat too much fish, though the Asian market compensated.

When I met Nault in the harbor he was preparing his “Gold Nugget” for a three-day halibut hunt — preparation that includes baiting 3,500 hooks with undersize pollock carcasses, although that part of the work Nault left to his deckhands. He talked of quitting the business soon because he sees the same “drastic changes” in the fisheries that have overtaken other ways of life.

“We are losing the small American entrepreneur, and we’re losing the family business, whether it’s farms, whether it’s small fishing, whether it’s small grocery stores, whether it’s mom-and-pop operations of all kinds,” he said over coffee. The Walmart in Kodiak was a new apparition, like the occasional cell tower. “We are going towards the corporate mentality. The government is growing by leaps and bounds. With the corporation take-over mentality and the government exploding, those two things to me spell, I don’t know — it’s real scary to me.”

Nault has since moved to California.

I’d heard similar words from Mary Jacobs, who in 1979 led Kodiak’s first all-women fishing crew on the 29-foot “Renaissance.” With the fishing quotas, “Lots of times it’s the crooks that get in, and it’s taking away from some of the honest lifestyle that we had here,” she said. “Maybe some of the issues like dragging, which are destructive to the bottom of the ocean, aren’t being taken up because we’re too busy fighting for our piece of the pie. So what happens to the resource?”

Nothing, according to men like Scott Smiley, who headed the government-funded Fishery Industrial Technology Center on Kodiak.

“We have no endangered stock,” he told me with the kind of finality that suggested he didn’t like my questions.

But what of the demise of King Crab, a fishery that went bust in 1983 in Kodiak, and of shrimp, which crashed three years later?

“Clearly knocked off by environmental change. We know that it was probably not overfishing.” It’s not clear how the difference was as absolving as Smiley was making it sound.

Alaskan logic has it that the collapse of fisheries around the world can be blamed on overfishing but the disappearance of a certain type of sea animals in Alaska augurs nothing. It merely has to do with “environmental change.”

Adamant that no one “gets it” (meaning that I was the dumb one who wasn’t getting it) Smiley handed me sheets of statistics showing the wealth of the surrounding seas — $1.2 billion-worth of exported seafood in 1996, among other numbers. (His figures were deceiving. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration annual report lists just under $600 million in exports of edible seafood, with $1.78 billion in non-edible exports that year). He must not have been aware that the sheets were printed on the back of office scrap paper once used to circulate ethnic and obscene Christmas jokes (“Why did the snowman have a smile on his face?” etc.)

What Smiley’s figure didn’t show is a little perspective, Kristen Johnson, another fish biologist on the island, told me. “People give the last two or three years of data, not the 15-20 year time period to really look and say this is what’s really going on,” Johnson said. “The system is productive, but if you look at population numbers, fish landings have been declining for several years. We’re dropping down the scale all the time.”

It is the same old Alaskan gold rush story with a scaly twist: the gold nuggets are now good swimmers, although not so good that they can always evade ships’ drift nets, long lines, trawls, radar, sonar, GPS. Kodiak and the Bering Sea, once boundless, some years ago were at risk of becoming — like the rest of the world’s fisheries — barrels. Good management can keep fish harvesting at sustainable levels. But even governments are battling each other. Alaskans despise federal regulators, and some state-funded Alaskan boosters — like Smiley — are already blaming the potential demise of the fisheries on Washington’s meddling.

But it seems to have been just that sort of meddling that stabilized Alaskan fisheries, including in Kodiak. King Crab and shrimp haven’t returned, but other species are stable today. In 1998 Kodiak’s port landed 358 million pounds of fish, according to NOAA’s annual report. In 2020, it was 364 million. Salmon is a major industry on Kodiak. Total catch in 1998, the year I was there, was 26.5 million fish. Six years later, it was 14.8 million. But in 2020 it was back up to 23.9 million, and 30.2 million the following year.

That didn’t happen because Alaskan fisheries were left free to revel in their frontier mentality. It happened because the frontier mentality was tamed. It was mildly regulated. It happened because romance aside, there is nothing so destructive to natural resources than a frontier mentality chest-thumping its individualism. But even that may have happened too late.

Oil is by far the leading industry in the state, providing almost $5 billion in income to 77,600 workers in 2019. Fisheries are next, with 37,000 workers collectively taking in $2.2 billion, according to an annual report by the McKinley Research, a chamber of commerce-affiliated industry cheerleader. Kodiak, by its count, still had 5,800 workers in the fishing industry earning $228 million last year (the household income in Kodiak is 50 percent higher than in Palm Coast).

The number seems grossly inflated and masks some signs that Kodiak’s fishery is declining. The island’s cumulative catch was valued by more reliable government reports at $88 million in 1997. It was $120 million in 2019, but in inflation-adjusted dollars, the haul would have had to be valued at $140 million just to match the 1997 value.

Similarly, federal catch-share regulations ended the ravages to the King Crab and Snow Crab fisheries of the Bering Sea–ravages to fish and fishermen–as fans of “Deadliest Catch” can attest. (“Old regulations forced fishermen to race against the clock. Today’s catch shares have saved lives,” one of the “Deadliest Catch” captains wrote of what had been one of the most dangerous jobs on the planet.) But Alaska’s regulators canceled the 2022 snow crab season outright, blaming it on warming waters. If that isn’t the sign of a catastrophe, I don’t know what it.

The catch-share system reversed the devastation of the fisheries. Its equivalent, from carbon trading to effective net-zero emission goals, could do the same for warming waters, if now on a much longer time scale (the waters will warm a lot more before they can start cooling). But the same consumers of King Crab at your local Florida Publix are not inclined to support climate-change regulations the way Alaskans eventually accepted catch-share quotas. For Alaskans, it was a matter of economic survival.

You’d think Floridians would see it the same way as rising seas and intensifying storms continue to carve up the coast and erode one of tourism’s principal assets. They do not. The state is now entirely controlled by the GOP, so what Republicans think matters, and it matters almost exclusively. What they think is reflected in state policy. Florida “Republicans who believe climate change is happening are far more likely to say it’s due to natural causes, and only 35% believe individual efforts can reduce the pollution causing climate change,” according to one recent poll. Another showed older voters only tepidly worried about climate change, and uninterested in addressing its causes so much as building “resiliency” against it–a euphemism for building on, frontier-like, damn the consequences.

You’re familiar with the butterfly effect: the allegory that a butterfly flapping its wings at one end of the planet can cause a hurricane at the other. The allegory is meant to reflect the intimate connection between everything we do on the planet, and especially to the planet, no matter where we are. It sounds exaggerated. But there’s really nothing allegorical about the connection between the Floridian who substitutes chest-thumping “resiliency” for emission-lowering actions and the warming waters of the Bering Sea that are devastating crab fisheries. We are those butterflies, flapping our wings in concert with our denialist gums and pretending it has nothing to do with those warming, rising seas all around us.

*

I retreated to the dinner table of Ann and Bill Barker. Ann owned Shire Bookstore, the only one on Kodiak. Bill was a retired schoolteacher who chaired an advisory committee to the Alaska Board of Fisheries. And there, after they’d spent two hours educating me about the island’s conflicted fisheries, the Barkers’ son-in-law, Matt Corriere, began talking about the winter night, five years ago, when his fishing boat, the Massacre Bay, struck a reef, rolled over and plunged him and three shipmates into icy, black waters off Kodiak.

“I found it very exciting at the time,” he said, laughing, about the very first moments after the 86-foot crab fishing vessel rolled. It’s not a happy laugh. It’s more self-ridiculing. He was the youngest member of the crew. The others knew better. “I was joking with the other guys, laughing. I thought this was great. Young crab fishermen have an idea that they are invincible, and I didn’t think anything was going to happen. I mean, I’m in the water in the middle of the night. This is just part of fishing. I remember saying that. They were all kind of freaking out and I said, ‘Hey, we’re crab fishermen, this is great.’ Not for one minute did I think that we would not make it.”

Matt was 23 at the time. Bill Corbin was 45, Tom Salisbury 48, Jock Bevis 42. (Remember that name: Jock Bevis.) They all died — one of a heart attack as he was jumping in the water, the other two of hypothermia, even though all wore survival suits designed to resist the water’s lethal cold, at least temporarily. Matt blames alcohol and drugs, which were found in the skipper’s bloodstream. The skipper had fallen asleep as he piloted the boat to a different destination at 3 a.m., and he struck a reef, opening a 9-foot gash in the bottom of the boat.

Whether because he was younger or healthier or in a different mental frame of mind, hypothermia spared Matt long enough that he made it to a rocky shore, where he was rescued by the Coast Guard helicopter that had already retrieved two of his three shipmates’ bodies.

“For about six months afterward I was really kind of a mess,” Matt said, still punctuating his story with a nervous laugh. “It just made me grow up a little faster. It’s changed me completely. I was young and wild and did many things I will not speak of now. I stopped commercial fishing, basically.” But he has no fear of boats, or of the ocean — the ocean he cussed and cursed after making it to the rocks of Humpy Cove the night of the accident. (He’s now a general contractor who owns his own company.)

Matt’s is not an unusual story on Kodiak. The island until the 1990s was losing on average 24 commercial fishermen a year to the sea, an occupational fatality rate 20 times the national average, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Eighteen fishermen died in 1993, the year of the Massacre Bay accident.

Every time the island lost a fisherman, all of its other conflicts receded to a disagreeable black dot. But fishing safety has been another huge improvement, not least because of federal and state regulations, like that quota system the “Deadliest Catch” captain boasted about. Between 2000 and 2014, average annual fatalities were cut by more than half, with further declines almost every year. In 2015 and in 2022, no one died on the job.

The Barkers still fished for salmon, as many residents on the island do, not commercially, but for pleasure, for the culture of it especially, for canning. Before I left they handed me a stash of cans. I rationed them for weeks as I crossed Montana, the Dakotas and the Midwest, feeling every time I cracked open a can as if I were tasting Alaska at its purest. I’ve been on a hunt for that salmon taste ever since.

*

“When you drive along an old back-road in the Lower Forty-eight and come upon a yard full of manufactured debris, where auto engines hang from oak limbs over dark tarry spots on the ground and fuel drums lean up against iron bathtubs near vine-covered glassless automobiles that are rusting down into the soil,” John McPhee wrote in Coming Into the Country, “you have come upon a fragment of Alaska. The people inside are Alaskans who have not yet left for the north.”

On Kodiak, the Kalakala was part of that strange northern migration of junk that keeps blackening the Alaskan landscape from Kodiak to Prudhoe Bay and everywhere in between where human beings tread, because that’s what they do: they remake their surroundings in their image.

I spotted the Kalakala by chance within an hour of driving off the ferry onto Kodiak as I was wandering aimlessly wherever there was gravel or asphalt for my Venture. What looked like a monstrous UFO was moored next to piles of junky metal and a couple of trucks. It would catch anybody’s eye. I parked, approached, walked up to it: I could touch its steel walls from the wharf. Even its name sounded outlandish.

I took it to be indigenous to Kodiak, a mass of rusting history, until I spotted Peter Bevis, the closest thing I came to a bear on the island, as his friendly smile welcomed me from behind a jungle of a beard.

We struck up a conversation as if we’d always known each other, and spent the next two hours walking the decks and bowels of the Kalakala. He’d flown in from Seattle that morning. He was there to prepare for the Kalakala’s journey home. Home to Puget Sound.

He’d been working on it for years, this sculptor who spent fishing seasons in Kodiak to pile up money and have time for his art the rest of the year, who’d lost a brother to a crabbing accident–the same Josh Bevis who died in the Massacre Bay accident–and who’d fallen for the Kalakala to the point of passion after he’d spotted it rotting on the same wharf years before.

This pile of junk had found its savior. Bevis wanted to do nothing less with the Kalakala than Picasso had done with that rusty old handlebar, transforming it into one of his most famous works of art with one touch of genius. To Bevis, it was just a matter of bringing the Kalakala back to its artistic roots.

It had started life as the Peralta, a San Francisco Bay ferry in 1926. It partly sank two years later, partly burned a few years after that and was sold to the Puget Sound Navigation Company, which had it rebuilt and put back to work in time for July 4, 1935 . It looked like a stepchild of Norman Bel Geddes, the designing father of streamlining, though he didn’t have anything to do with it. It was renamed Kalakala (pronounced Kah-lock-ah-lah), a Chinook word meaning “flying bird” (but also “hen” or “eagle”).

This bird was 276 feet long. Though prone to collisions because of the way the design restricted the pilot’s visibility, it became known all over the world for its art deco style, its 500 upholstered armchairs, its metal walls, its rivets-replacing welding, its own band (“The Flying Birds,” of course) and ballroom dances on weekend nights when it took a break from ferrying 110 cars and 2,000 people at a time.

Its parties were broadcast on AM radio. The New York Times called it “radically different from any ship of her type anywhere in the world. Outwardly she looks like a giant wingless hydroplane; her interior is like the lounge of a luxurious hotel.” In 1945 it was the first boat to experiment with radar. The Saturday Evening Post called it “the greatest ferry tale since Noah,” according to Bevis, himself partial to the same kind of puns.

By the time of the 1962 World’s Fair the Kalakala had been in decline, its operating costs rising, its car deck shrinking, its collisions multiplying, its hull decomposing. In 1967 it was sold to the New England Fish Company for $101,551, exiled to Kodiak, and used as a fish processing plant, its bowels the site of a billion disembowelments. No longer seaworthy, it became a dockside cannery in 1972. Then it was abandoned, left to rust and rot in Kodiak Bay’s mud.

Peter Bevis first saw it in 1984. He saw it as a beautiful sculpture to unwrap, the opposite of the way Christo liked to do to cherished landmarks.

“It’s not so much what I see as what I feel,” he said as we walked the Kalakala’s hazards–he as if it were his childhood bedroom, me as if I were navigating tripwires. Bevis spoke in lyricisms: “One hundred million people rode this ferry. At the time that was half the population of the United States. There’s laughter in the steel, there’s music in the metal, there’s dancing on the floor, and to me that’s still there. There’s still people who remember the Kalakala.”

Despite the minor exaggerations (it may have ferried 30 million people at most: Bevis always dreamed bigger than any reality allowed), as we walked through the ship I could see what he was talking about: the scrapes left on the walls by vehicles too big for the deck as America’s cars finned for suburbia got much bigger than the Model T’s and Model A’s the ferry was built for; the self-confident immensity of the ballroom upstairs; the romance of the observation deck out front, with Kodiak’s Old Woman’s Mountain range in the distance; the last surviving period bench in one of many half-arcaded alcoves.

But the ballroom had also reminded me of the uneasy atmosphere of that hotel’s deserted playrooms in The Shining. And when we came to the ship’s famous engine deep below the waterline, it was as if we’d penetrated the sepulchral recesses of a pyramid, the massive, single 3,000-horsepower diesel colossus lying there, unhappily disturbed.

Bevis wanted to save the ship, bring it back to Seattle, turn it into a museum. He’d started the Kalakala Foundation a decade earlier to raise the money, clean the boat of three years’ worth of bonfires. It raised little. He paid for the $500,000 expense, maxing out 10 credit cards, borrowing against a foundry he owned, spending an uncle’s inheritance. He hadn’t secured a tugboat yet but said the trip back to Seattle would happen in two weeks. I didn’t believe him. When I asked him if he thought it could make it down, Pacific winds and all, he said, “we don’t say ‘down.’ We say home.”

I was wrong. That November, it made the 16-day journey back to Seattle. I would see Bevis again late there the following year, when my own journey took me to Washington, and for the last time. The Kalakala made it home, but it was never adopted again. It never became a museum. It never recovered its art. The foundation filed for bankruptcy in March 2003, owing Bevis $1 million and vendors $200,000. The boat was sold for scrap and demolished. Bevis, heartbroken, abandoned Seattle in turn, angry at a city he felt had betrayed him.

He died in mid-July 2022 in San Diego. He’d tried the impossible, turning a sarcophagus of junk back to a glory that may not even have existed quite like he thought. The Kalakala was his Alaska: perfect only in the imagination.

*

Alaska’s detours in irony never cease. One of the stories Alaskans like to tell about themselves is that they’re the last rugged, self-made individualists left in America. But they happen to live in the most socialist state in America, thanks to the Alaska Permanent Fund. That’s the black gold kitty that has ensured every Alaskan–man, woman, child–receives an annual dividend check averaging $1,500, drawn from the state’s oil sales.

Last September, every one of Alaska’s 660,000 eligible resident (a quarter of them children) received $3,284, including the extra $662 lawmakers decided to add to help with energy costs. It was the highest payout since the fund began in 1980. The only other time the fund was raided for an extra $1,200 per resident was in 2008, when then-Gov. Sarah Palin, that paragon of anti-socialism, signed the bonus into law.

It’s the country’s only equivalent to a basic minimum income, the sort of social-welfare idea that keeps circling without finding a footing–except in rugged, self-sufficient Alaska. It’s a great idea, of course. It’s how any state’s revenues should be invested and shared. But some Alaskans typically go nuts when the fund’s hand-outs are called for what they are. Alaska needs its mythologies, as all Neverlands do.

*

The day I left the island I took a drive in the country on one of Kodiak’s two roads. The pavement ends after a few miles, and a few miles after that a sign pops up warning of the absence of warning signs ahead. Real wilderness, you think. For a moment it even looks like it: A salmon spawning marsh here, a buffalo herd there, a dirt road of switchbacks and precipices and bear-traveled trails.

Then the punch line near the end of the road, about 50 miles from Kodiak: U.S. Navy trucks, satellite dishes, a launch pad getting prepped for an inter-continental ballistic missile test flight, and a rickety sign by roadside that says: CONSTRUCTION SITE FOR KODIAK LAUNCH COMPLEX.

The $28 million facility on 3,200 acres was begun as a state venture to attract the private sector. NASA and the Air Force had funded all but $5 million of the pad by 1998. A few weeks after I left the Air Force launched a Minuteman 2 missile that traveled 450 miles up and 1,100 miles south before splashing into the Pacific. What the Pentagon was forbidden to do from a Montana launch site, it could now do to its strategists’ content from Kodiak.

It has since been renamed the Pacific Spaceport Complex, run by state-owned Alaska Aerospace and kept rich by the endless welfare of federal defense contracts–every state’s basic minimum income–and private satellite launches, with a few growing-pain failures along the way.

The launch complex was once an isolated nowhere at the east-central end of the island. The suburban effect is changing that. Residential homes are creeping closer. Nearby beaches are becoming more popular, the site’s detractors noisier, the nimbyism louder.

I thought of something Mary Jacobs, the pioneer skipper of the Renaissance, had told me a week earlier about her love for the island: “All your problems are within 30 feet, and I think it’s that simplicity of life a lot of us want to hang on to. I don’t know if we can or not, but we’ll do it as long as it’s possible.”

On Kodiak as in Alaska’s 581,037 remaining square miles, there’s always more room for the imagination.

![]()

Ray W. says

Note to Jimbo99: These articles exemplify what can happen when anyone mixes curiosity, wanderlust and intellectual rigor. Joseph Campbell, a 20th century American philosopher, advocated for a life punctuated by “fires of the mind.”

Thank you for introducing us all to your fires of the mind, Mr. Tristam.

Pierre Tristam says

Fires of the mind! What a superb line! Thank you Ray-Campbell.

Ray W. says

Michener, in one of his few non-fiction works, Iberia, described his effort to write a story about a Spanish legend based on two lovers who lived in Teruel.

A young man’s proposal was turned down by his intended’s father, but for one condition: the father gave the young man seven years to make his fortune in the world. The young man left the next morning, counting the days starting from the day he left. The father counted the days from the date of the condition. The young man returned seven years later to the day only to find his intended marrying another. Tragedy ensued, as the legend is the Spanish version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Michenor labored into the night testing perspective after perspective, until he hit on the theme of writing in the voices of the stones over which so many of the city’s young men left through the gates of Teruel, with many never to return. Once he had his perspective, Michenor tells of writing through the night until well past dawn, entirely consumed by the moment. To me, Michenor experienced the fires of the mind.

Some argue that the good life consists of each of four elements in an everchanging yet balancing mix: a life of action, a life of introspection, a life of fatalism, and a life of fun. While each element is necessary, none should prevail completely over any of the others, as an unbalanced life cannot be the good life.

Others argue that we are most human when at play.

I like to think that the adrenaline rush of a courtroom closing argument or the successful cross-examination of a state witness in the search for a simple truth that has eluded a prosecutor qualifies as a fire of the mind moment, but like Jimbo99 and all prosecutors, I am capable of wandering through life fooling myself.

Decades ago, while meeting with an expert witness, a leading psychiatrist who also commonly testified for the state, in a death penalty case, he asked me if I had ever cried over what I had been doing when I was a prosecutor. I looked him directly in the eye and stated, yes! Good, he said and went back to discussing the findings of his evaluation of the defendant. I never asked him to explain why it should be good for prosecutors to cry or whether he thought all prosecutors should have that experience, but I was thinking of a number of moments in cases when I realized that I, like all people, am susceptible of failing to discern when I was being used by people to harm other people. I knew that alleged victims and even police officers were capable of lying to me in order to harm others and I knew that I could miss the clues, the body language, the slight alterations from previous statements, the motives. I knew that if I missed those clues, I might destroy a family, a life, in the name of justice. Sometimes, I would cry and confide to my wife that I sensed that something was deeply wrong with a case, and I sensed that I lacked the wisdom of uncovering the truth, but I had to go forward. Prosecutors represent the state’s interests, not their own; they cannot simply drop a case whenever they cannot prove to themselves that their sense of injustice might be right.

Perhaps this is why our founding fathers refused to give the power to convict to prosecutors, even though I have listened to many prosecutors bemoan the fact that they lack that power. Many of them want it, for a variety of reasons. Some believe that they should be the justice givers in society. Some prosecutors slowly become vicious over time, but just can’t see the change. When interviewing with Mr. Boyles in 1986 to become a prosecutor, he asked if I would give him a three-year commitment to justify the investment they were about to make in me. I had returned to Daytona from Sarasota to prosecute in my home circuit. I told him my plan was to be a prosecutor for five years and then evaluate who I had become. I told him that if I did not like who I had become, I would quit. I knew then that few people, if anyone, were ever raised to be a prosecutor and that living in that world would change me. I sensed that living a life of prosecution might turn me into someone I no longer trusted. As time passed, I was often troubled by what I saw other prosecutors do to people and how some of them interpreted the world through a lens of vengeance. Perhaps this explains, if only partially, my common focus on the importance of the many checks and balances purposefully inserted into our Constitution.

As an aside, a now deceased friend of 30 years had served as a Metro-Dade deputy sheriff. We raced together in AMA-sanctioned endurance races, starting in 1982, and I was his crew chief in 23 Daytona 200s. After he retired, he moved to Port Orange. His wife bowled with my wife in a lady’s league, and we often went to dinner together on those nights. Occasionally, he would descend into a rant about how society had lost the war on crime and that Miami was the black hole of hostility in the universe. I would place my hand on his shoulder and remind him that it had taken 25 years to get him to this moment of anger and that it would take another 25 years to bring him back and that I was a patient man. He would apologize and dinner would resume.

Laurel says

Ray W.: You certainly know better than I, but I would think that a prosecutor’s job is to find the truth, while a defense lawyer’s job is to defend at any cost. To me, there should be no other way. A prosecutor should not have the luxury of opinion. However, “truth” is often a point of view. That would make me cry.

As for “Others would argue we are most human at play,” that is something I would argue against. We’ve all seen cats, dogs, horses, birds and most creatures play, even as adults. It’s life in practice, but it is not specifically a human trait. I’ve even seen a snail play in a fish tank, riding bubbles up, dropping down, and riding up again, over and over! Maybe we are most human when we recognize the human in the next person.

I see fires of the mind different, at least for me. It’s when I’m drawing something, get stuck, walk away, worry about it, come back and see what I missed before and correct it.

PS: I love Joseph Campbell. I’ve watched his series over and over, and can do it again to learn something I missed before.

Ray W. says

Thank you, Laurel. As I have written many times, I hope to provoke responses to my comments. Keep them coming, please. I often find myself agreeing with a commenter who offers a more complete understanding of an issue.

Denali says

In the spring of ’78 I carried a dog eared copy of McPhee’s book in my backpack as did hundreds of other young men wanting a part of the Alaskan adventure. I had no job or prospect of one. I had my Jeep, $500 in my pocket and an American Express card I swore not to use when I crossed into the country just north of Beaver Creek. A few of us stayed but when the first snows came most went back over the highway to the lower 48. Being a structural engineer I promptly put my education and experience to work by becoming a commercial fisherman. First out of Seward for Halibut and then Homer for crab and shrimp and finally fishing the Bering Sea for King Crab, Grey Cod and Pollack. Met my wife in Homer and 42 years later she still lets me live with her. The fishing life became a little too hit and miss so I fell back on my engineering skills and became involved with several major projects throughout the state. I would debate you on the value of the quota system of fishing verses the old derby style but that would take many more beers than either of us can hold in our two hands. I will say this the quota system as intended will save fisherman’s lives, however, it does not fully address the economic side of boat payments, insurance, fuel and groceries.

Your Alaska was, while different than mine, very much the same. Mine was a bit more on the wild side where a common phrase was to fornicate, fight or go for your guns. In Homer a man was arrested for killing another over a card game. At the trial the judge made the statement that the deceased was a know card cheat therefore he deserved what he got and the defendant was free to go. And then there was the guy who after being asked to leave a bar drove his snow plow into a dozen parked cars and smashed the front steps of the bar. After being arrested and placed in a squad car he kicked the windows out and ran from the cops, yes he was handcuffed. Two years later he was elected as mayor. As Tom Bodett said, it is the end of the road.

Alaska will always be that land of dreams and opportunity. It will always hold its mystique and its sense of adventure. It will remain that bucket list trip yet will remain elusive to many, even some those who have visited will never understand her. She is a land of contradictions and congruity. She is the past and she is the future. If you treat her with respect, you will be rewarded; we were.

Pierre Tristam says

Denali, your handle now makes a lot more sense. I love these stories, all these connections in space and time.

Alaska My Dream says

Ah, Alaska. When I was a kid, my dream was different from other kids. They had dreams of marriage and Hollywood or just leaving our small po-dunk town for the city. Not me. It was never my dream or even desire to move to FL. I hate the heat and when I say hate, it feel like I’ve entered hell in this state. I’m slowing working on a path out of here because this state and these people are not for me. I don’t like neighbors this close. All this fake patriotism and fake parental rights and fakery all around under the guise of kids. Stop using kids Florida as an excuse for hate. I digress. I grew up somewhere where no one cared what or who you were. You were just (name) and that was it. This state…

Anyway…my childhood dream was to somehow amass a substantial amount of wealth and buy thousands of acres of land in Alaska and preserve the land from oil drilling, hunting, and just let the wildlife thrive. I also wanted to buy thousands of acres and build animal sanctuaries that I would pay people to care for all animals big and small. I was an odd kid I suppose. I’m an odd adult because I still want those things. Maybe in another life, I’ll be fortunate enough to have the means to care for those that were here before us and will be long after we humans are gone.

Laurel says

Denali: The thing about Florida is that the vast, vast majority of people here came from somewhere else. I have banged my head against the wall, in frustration of the masses who come here and who care so little about this beautiful state, so many times, wishing it would somehow not happen.

I, too, must have been the same kind of odd kid as I wanted basically the same thing you wanted, and I, too, have thought “maybe in another life.” Florida has been raped by developers for decades and decades, and everyone who is tired of snow heads here and works to change paradise. Alaska has the advantage of freezing people out. Unfortunately, people tolerate heat better.

Michael Cocchiola says

I have nothing to add to what’s already said except thanks for these incredible musings.

Jane Kranz says

Wonderful writing. Thank you

Kodiak Kid says

As a fisherman before the quotas and after them, your ramblings make very little sense. Fish have seasons where the conditions/weather can dictate if the run is more substantial. Plain and simple. Overfishing could have been a reason in the 70’s, but you are talking about a time when the restrictions were basically zero. Sorry, you missed out on the positive aspects of life on ‘The Rock’ during your brief stay.