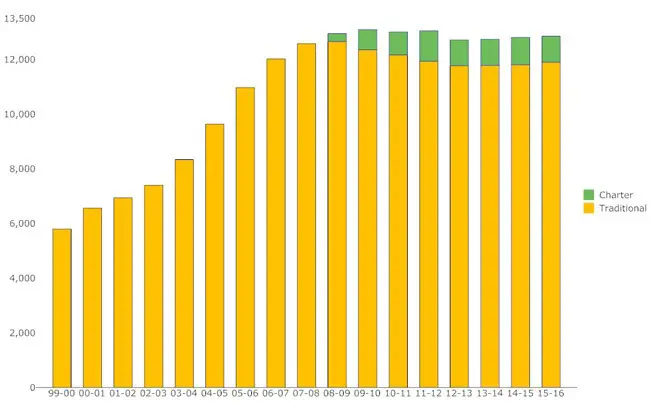

For the eighth straight year, Flagler County schools are seeing their enrollment remain flat, with minor month-to-month fluctuations up or down, and the same steady proportion of students—about 8 percent—attending charter schools.

The latest figures show the continuation of a stubborn trend: while the county’s population has increased between 1,000 and 1,500 a year since the housing crash, the school-age population has not, an indication that what population growth the county is experiencing is mostly made up of retired or non-working people. Working-age families with children are moving too, of course, but not in enough numbers to more than replace those that are leaving. The net effect is flat enrollment numbers.

Enrollment figures for mid-December show a total district school population of 12,825, still below the peak of a little over 13,000, reached two years after the housing crisis began, though the difference between the peak and existing numbers, while small, has nevertheless affected school funding more than the numbers show.

State funding is driven by enrollment, though the numbers can be deceiving: Two years ago, the Legislature changed the funding formula so that the state pays for only six courses per student per year, even if the student takes additional courses. Those additional costs must be borne by local districts, and of course some students do just that, inflating the full-time equivalent number of students that are reflected in total enrollment numbers.

Eight of the district’s nine traditional public schools are under capacity, as they have been for almost a decade, especially the district’s two middle schools: Indian Trails is at 55 percent capacity, Buddy Taylor at 69 percent. Mid-December enrollment figures show neither school gaining. Elementary schools are at 87 percent capacity. The one exception is Old Kings Elementary, which is near 100 percent capacity. The two high schools are at 87 percent capacity.

Overall, the district has 2,463 more spaces, or “student stations,” than it does students. While the district would welcome additional enrollment, the extra capacity is not all bad: it means there’s still time before the next school needs to be built.

“We should be in decent shape for the next five years,” Colleen Conklin, who chairs the school board, said during a workshop on school concurrency—a technical term that means whatever development takes place must account for concurrent needs such as additional schools, additional parks, roads, and so on.

The likeliest area that will be in need of a new school in several years, a consultant the district hired to analyze its concurrency needs said, will be near the new Matanzas interchange with I-95.

Thomas Harowski, president of TMH Consulting, summed up the district’s enrollment and projected growth during a workshop in mid-December, though the most recent enrollment figures were not discussed then. But Harowski provided a broader explanation of the paradox of Flagler’s growing population even as its school population remains flat.

“Families as you come out of these time periods tend to be the last to relocate because they’re really job-driven,” Harowski said, referring to the housing crash. Families have to know that the economy is going to be steady, and they have to know that jobs are waiting for them. Absent that, “those families are not going to relocate as readily. So you’re going to see them come on the back end of the housing growth rather than the front end.”

Flagler County itself has weaknesses in the sort of housing that translates into school children. People who fill those houses tend to be blue collar, foreign born or Latino. There’s been some of that growth in Flagler, but not the sort of growth seen elsewhere. Rather, the growth in Flagler has been driven by short-term rental homeowners: that’s where much of the housing growth has been concentrated, Harowski said.

Nevertheless, he cautioned school board members. “We’re looking at a relatively narrow time period where we haven’t seen a lot of students coming out of the housing that’s been built, but we’re also coming out of a period with the housing bubble and the collapse where we’ve really had an extraordinary condition for housing development, really in the history of the country,” Harowski said, “and I’d be a little concerned about making long-term policy decisions based on the rollout form that period until we give some opportunity for that to settle down a little bit.”

The projections are encouraging—but with caveats at every turn.

There are still 17,000 undeveloped lots in Palm Coast, for example. But there are no indications of wholesale growth. Permitting was below 300 a year in 2010, 2011 and 2012, it rose modestly to a little over 500 in 2013 and has continued to rise, albeit slowly, just past 600 in 2014.

The expectation is that between 2015 and 2020, the district would add 460 students a year, almost half in elementary schools, or the equivalent of 1,400 housing units, Harowski said. But, he warned, those projections are based on those of the University of Florida’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research (better known by its acronym, BEBR), whose demographic numbers have tended to be more irrationally exuberant—which is why Realtors and home builders love them–than empirically justified.

“Experience shows us that the BEBR numbers tend to run high,” Harowski said. “I’ve been through four censuses with them, and pretty much every time the census comes out BEBR has had to come back and they roll their projections back to some degree. It’s important to look at this because it is the official state projection, but it certainly I think would be considered the upper end of what would be anticipated in terms of student growth. The rates that we’ve actually been seeing, FTE [or full-time equivalent enrollment] has been around 100 per year. FTE is a little different in terms of the actual student total relative to the concurrency numbers.”

The enrollment increase from 2014 to 2015 that Harowski pointed out is an increase of 150, or only about 30 to 35 percent of the BEBR projection. And of course even that 150 is larger than the December numbers showed.

For all that, Palm Coast and the county still have a dozen major developments approved for the mid- to long-term future, including Town Center in Palm Coast (2,178 housing units), Neoga Lakes (7,000 units), Old Brick Township (5,000 units), Hunter’s Ridge (1,777 units) and Palm Coast Park (3,600). The dozen developments add up to 24,200 housing units, with build-outs projected through the beginning of the 2030s. That doesn’t include Palm Coast’s unbuilt lots.

Development is coming, and with it swelling enrollment numbers. But the when is still in question.

Nancy N says

Population numbers aren’t the only factors in the school district’s lack of growth. Fact is, local students have plenty of other options besides Flagler County Schools – and more and more parents are taking advantage of private and homeschool options.

Our own daughter left Belle Terre Elementary several years ago when Flagler moved to full inclusion for all autistic students in the district. Two school years later, we are still trying to undo the damage from her year in the pilot program in that initiative. We moved her first to Florida Virtual School, and then to homeschooling with the PLSA program (now Florida Gardiner Scholarship).