Note: During Matanzas High School’s School Advisory Committee (SAC) meeting on Tuesday, Jan. 14, at 6:30 p.m., Jo Ann Nahirny, who teaches SAT Prep, will offer tips to parents about how to help students prepare for the SAT. She’ll also talk about what students can do to help improve their own performance on college admissions tests. Information will also be available about free, online resource students can utilize beginning in the middle grades on through high school, to help get them ready for challenging college course work. All are invited.

By Jo Ann Nahirny

My 19-year-old son, Michael, will graduate in just four short months –from Stetson University.

Yes, you read that correctly. He’s 19, and on the verge of earning his undergraduate degree in Business Management, with double minors in Business Law and Business Systems Analysis — and a GPA approaching 3.9.

This isn’t occurring because he’s a genius, or because my husband and I hovered overhead like those helicopter parents teachers (like me) dread. This has been a work in progress since our children were born.

This isn’t occurring because he’s a genius, or because my husband and I hovered overhead like those helicopter parents teachers (like me) dread. This has been a work in progress since our children were born.

My husband and I planted and cultivated the seeds of education before our kids even entered school, selling Catherine and Michael on the idea that they wouldgo to college. To be sure they’d get there, literacy assumed a position of primacy in our home. We read to them every single night, until they learned to read aloud to us, then finally, almost naturally, they grew to love reading enough to fall asleep nightly with a book in their hands. Every evening after dinner, they sat at the dining room table and did homework. They checked off completed assignments in their planners and showed them to us before they could watch television or play outside. By middle school, the “homework habit” was so deeply ingrained that we rarely, if ever, had to oversee the process.

We continually emphasized that if they did well in school, and stayed out of trouble, we’d pay for college so they could concentrate on earning a degree without incurring debt.

So they excelled, mostly of their own accord, but not without urging (admittedly, sometimes even downright nagging) from us. We scrimped and saved so we could make good on our promise, starting out by putting away $1 a day per kid when they were babies, then a few years later, upping that to $2 per day, then $3, then $4, saving tortoise-like, for two decades.

When they both showed interest in Stetson University, where tuition (not including room and board) exceeds $37,000 annually, silent panic set in. We knew we’d never amass enough to pay even a year’s worth of tuition at Stetson for either kid. What would we do?

Thank God for guidance counselors who steered us toward “early college,” Bright Futures and myriad scholarships.

Catherine dual enrolled as a senior in high school. Michael took his first class at Daytona State just as he began attending Matanzas High School. He did this because he attained “college ready” scores on the SAT after taking this test as part of the Talent Identification Program sponsored by Duke University – and arranged by his seventh-grade teachers at Indian Trails Middle School.

Catherine earned almost a year’s worth of college credit at Daytona State during her senior year in high school. Michael ended up earning his Associate’s degree before he even officially graduated from high school, and entered Stetson with more than 60 credits under his belt –credits that cost us nary a penny.

They both received Bright Futures and other scholarships from generous civic groups and community organizations. Stetson University also awarded a Dean’s Scholarship to my daughter, and two years later, a Presidential Scholarship to my son. Yet even all these combined sources of funding didn’t fully cover the hefty tuition bills, fees, and expensive textbooks, so each year we turned to what we’d saved to pay the remaining balance. And somehow, much like the biblical account of the five loaves and the two fish that fed five thousand, the money miraculously stretched out just long enough for us to be able to write out one last check to pay for our portion of Michael’s final tuition bill just this month.

Ultimately, my daughter finished college a semester early, earning a degree in elementary education last January. She landed a teaching job a month later –at a time when the unemployment rate for youth ages 16 to 24 stood at more than 16 percent. My son was recently tapped for a management training program at the Winn Dixie where he’s worked since he was 15. He’s now serving as a manager trainee while finishing up his bachelor’s degree, and he’ll continue doing so while pursuing his MBA at Stetson starting in August.

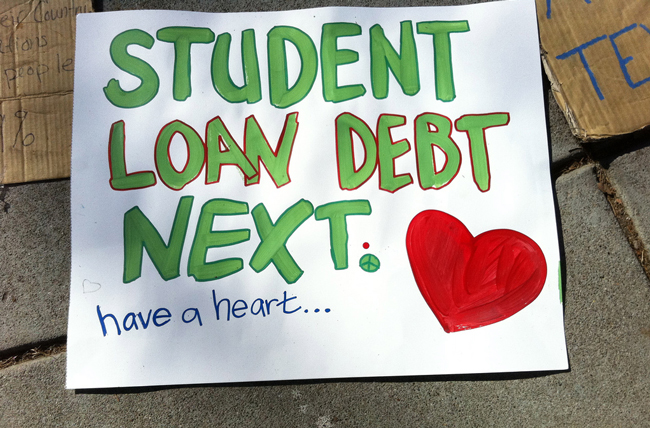

Though CNN reported last month that the average debt load for the class of 2012 was $29,400, we’ve managed to reach our lifelong goal of getting our two kids through college debt free. And they’ve both got jobs besides.

Are we proud? Hell yes. Bragging? Probably.

But the point is, none of this came easy. It literally took a lifetime of planning and effort on the part of our entire family.

And that’s why it frustrates me that I have students (and their families) who don’t plan ahead. Some don’t even think about taking the SAT until it’s almost too late. Just this week a young man stopped by my classroom to borrow a guidebook to review for the SAT. He’s a senior who’s taking the test for the first time on January 25–long past the application deadline for most colleges.

Earlier this month a parent contacted me about her son’s SAT scores. She’d only just now realized his scores were a far cry from what he needs to get Bright Futures, and she was panicky. I helped her as best I could, but later I wondered why she and her son hadn’t formulated a long-term game plan to reach their goals, and why he hasn’t bothered to apply for even one of the dozens of scholarships available to Flagler County high school seniors.

Another mom recently called me and offered me top dollar for private SAT tutoring. I turned her down partially for ethical reasons. (I teach an SAT prep elective at Matanzas and students there can take it for free; I wouldn’t charge for something kids can get in my class gratis.) But I mainly refused because the daughter’s schedule was so jam-packed with sports practices that she was only available for tutoring for one hour on Sunday nights. One short hour a week at the eleventh hour wouldn’t likely help her scores. That she dedicates more than a dozen hours a week to playing a game that probably won’t net her a scholarship, but can’t spare more than an hour to brush up on academics, puzzled me.

There are more than seven million high school athletes, but college roster spots for just two percent of them. If this student-athlete had spent as much time on studying to bolster her GPA and SAT scores as she did on throwing a ball, she’d have had a much better chance at getting a scholarship. These days, many universities, rather than lose bright students to less-expensive public colleges, offer sizable amounts of aid based mainly on academic merit. An Education Department study released last fall showed that the percentage of students receiving merit aid grew so rapidly from 1995 to 2008 that it rivaled the number of students receiving need-based aid. Merit aid is where it’s at in college financing these days.

More than 20 years ago, my husband and I started our kids on the road to college success by teaching them to read, instilling in them good study habits-–and by saving a mere dollar a day. These little steps ultimately left both us, and our children, free of college debt today.

![]()

Jo Ann C. Nahirny, a 1985 graduate of Columbia University and a National Board Certified Teacher, teaches English at Matanzas High School in Palm Coast. Reach her by email here.

Leave a Reply