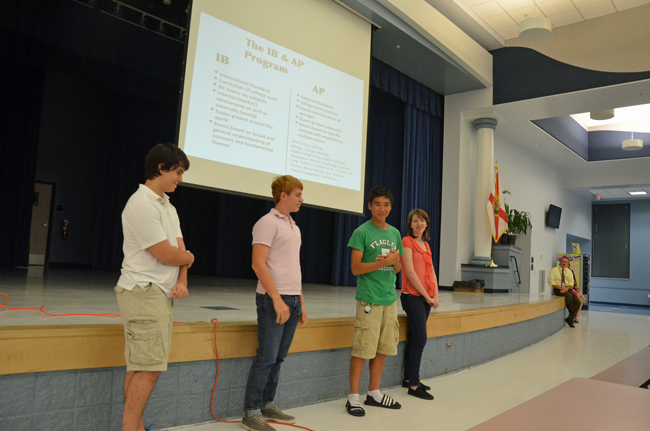

One after the other, the four students turned into myth-busters.

Click On: |

They were talking to a crowd of some 250 people who’d filled three quarters of the cafeteria at Buddy Taylor Middle School. Two days earlier, the same event had drawn some 175 parents and students at Indian Trails Middle School. Their aim: to demolish the stereotypes that too many people in Flagler County attach to the school district’s International Baccalaureate program, better known as the IB, and too often known as a gulag of a program on students’ time, social activities and family life.

Not so.

The reason IB students may seem like they don’t have time for anything, Barrett Manfre, an 11th grader at Flagler Palm Coast High School, said, is because they tend to be involved in so many different activities beyond school. Manfre himself is in five clubs, two councils (including the newly founded IB council) and two varsity sports, “yet I get to bed at 10 p.m.,” he said. Sure, there are a few late nights, but it’s not the routine, and it’s not what makes for a great IB experience. “You don’t have to be the genius of the class top make it through IB,” Manfre said. Rather, it takes persistence, dedication, a good work ethic, and the rest will follow.

Nicole Fuller, a 10th grader in the pre-IB program at FPC, rattled off a long list of clubs and other activities she’s in as well as she described challenges she welcomed and a method of learning she loves. “You learn way more than you think you’re going to learn,” she said, whwether through Plato, Jacques Cousteau or “Sophie’s World” (an extremely popular Norwegian novelization of the history of philosophy that’s sold tens of millions of copies since the early 1990s).

Then there was Mike Safarty. That the 12th grader at FPC was willing to spend two hours of a weekday evening talking about the IB instead of slaving for it should tell you all you need to know about how manageable it can be. Reasonably speaking, Safarty shouldn’t have been at Buddy Taylor that evening. He should have been sweating over one of the biggest hurdles of the IB program, the dreaded Extended Essay, a 3,000 to 4,000-word mega-work seniors have all summer and half the fall to produce. The first draft was due that very evening.

Mr. Pig Explains Pigdom[media id=139 width=350 height=250]

Yet here was Safarty, his paper in hand (an inquiry into the justifications for terrorism, if there ever are any; his conclusion: no such justifications exist), looking strangely relaxed and ready to tell his audience—and future IB students—not to sweat it: these days in his senior year, it’s not even as if he has that much homework to do. There’s a lot of studying, but with time management, it’s all doable. So doable, he said, that this year the IB group at school spent plenty of time building an IB float for the homecoming parade.

And then there’s this: if college is the goal, there’s no surer way than going IB. “It kind of separates me from the pack when it comes to college applications,” Safarty said.

That’s the point IB coordinator Roger Tangney and FPC Principal Lynette Shott played up most to the assembly. The IB is a ticket to college, to generous scholarships, to free college credits, and to the most well-rounded, most enriching and most rigorous education the school district has to offer. “It’s so amazing when we look at the colleges that our students are able to go on to from our local schools,” Tangney said, “and then become movers and shakers, to people that are changing the world.”

That’s what the IB is designed to do. With a very distant connection to the United Nations, the program was designed in Switzerland in 1968 as a way for the children of diplomats who traveled a lot to have continuity in their education. There were just seven IB schools around the world at the beginning, including the United Nations International School in New York. But the idea quickly won converts. The IB organization now has some 1,300 schools around the world, with Florida one of its fastest-growing regions.

The actual diploma program at FPC is for juniors and seniors, but the pre-IB program extends to 9th and 10th grade. The entire program has some 200 students this year.

Shott wants to double the number. Tangney has been leading orientation sessions for late middle school students annually, to encourage enrollment in the pre-IB program. Shott felt that waiting until middle school was too late. She proposed introducing the program to students as early as 5th grade. So the district sent out 800 letters to invite parents and students to the two introductory sessions at Buddy Taylor and Indian Trails (which took place on Oct. 15 and 17). The response, totaling more than 400 people for the combined events, was impressive.

The key, of course, was letting students currently in the IB program describe it in their own words, then letting parents (or students) ask questions. There were many. Most revolved around the usual concerns: if the program costs anything extra (aside from the odd lab fee, it does not: the district foots the annual $300,000 bill). If the students are isolated from the rest of the student body. “Isolated” is a misnomer: IB students are grouped together, but they consider their groupings more along the lines of a “family” than an isolation, and, aside from classes, they are as much a part of the school as anyone else—in clubs, sports and other activities. They are no less “isolated” than are, say, students on a more vocational track are isolated among themselves. The inevitable question about homework was also asked, repeatedly, and answered: yes, homework can be heavy, particularly in junior year, but by then, with the training students will have picked up in the pre-IB program, it’s a matter of time management more than anything else.

And IB teachers, Manfre said, “are not going to leave you hanging out there if you don’t understand the concepts.”

One teacher in particular got more attention than others in the students’ descriptions of the program, mostly in code. Jonathan Ling, a 10th grader at FPC, kept telling the crowd that “When you get to the IB program, you’re going to learn to dislike pigs intensely.”

He was referring, of course, to Jim Pignatiello (“Mr. Pig”), a chemistry teacher—and FPC’s 2011 Teacher of the Year—who, besides being the school’s most accomplished IB teacher, is also its most demanding: he was made for the IB. His students at first typically revile his teaching method. Being young, they confuse the method with the man, and end up reviling him, too. But the majority get beyond that. (You can see Mr. Pig explaining Pigdom in the video above.)

They eventually catch on, figuring out that what they revile most is what’s best about Mr. Pig, and about the IB: Teacher and program develop students who increasingly learn to trust their intellect, to discover their own potential and teach themselves. Neither Pignatiello nor the IB provide answers on a silver platter. But they provide the method of getting the answer. Students who figure that out end up worshipping the teacher—and the program. They learn that sometimes pigs do fly.

![]()

International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Program: A Guide

John Sbordone says

This program provides our kids the best opportunity to compete nationally available. At City Repertory Theatre we have had the good fortune to work with many IB students.They have been talented, enthusiastic, resposible and accomplished, while carrying a full academic schedule. Flagler County is fortunate to have this advanced program.