If you live west of the Intracoastal Waterway in Florida and don’t know what a barrier island is, the easiest way to find out is to drive east on a bridge that crosses the Waterway. When you reach the far end of the bridge, you’ve just discovered a barrier island. But you’ve only begun your discovery. Questions linger: how was it formed, what does it do, what plants and animals live on it, and what are its unique challenges?

I live and work on Flagler County’s barrier island, and I love every minute of it. About 10 percent of Flagler County’s population lives on this barrier island, but I bet if you asked folks who live there to explain what a barrier island is and how it was formed, they’d be hard-pressed to get it right. So, in the spirit of helping out the barrier-challenged, here are some facts that will make Coastal View readers barrier island experts, or very boring party guests.

I live and work on Flagler County’s barrier island, and I love every minute of it. About 10 percent of Flagler County’s population lives on this barrier island, but I bet if you asked folks who live there to explain what a barrier island is and how it was formed, they’d be hard-pressed to get it right. So, in the spirit of helping out the barrier-challenged, here are some facts that will make Coastal View readers barrier island experts, or very boring party guests.

Generally, barrier islands are long and narrow, running parallel to the coastline, sometimes up to 100 miles at a stretch. In Flagler County for instance, the island extends from Marineland to the south end of Flagler Beach, and continues on to Ponce Inlet in Volusia County, a total distance of about 50 miles. Separated from the mainland by shallow water areas, such as the Intracoastal Waterway, bays and lagoons, barrier islands often are linked together by narrow tidal passes. A perfect example of this phenomenon is Matanzas Inlet in nearby St. Johns County.

Scientists are uncertain about the formation of barrier islands, but current thinking is that, as the Ice Age ended about 18,000 years ago, glaciers melted and receded. Sea levels rose and oceans flooded areas west of the beach ridges that existed then. Sediments from the beach ridges were brought inland and deposited in shallow waters off the new coast lines. Over time, as currents and waves brought additional sediments, and inland rivers washed sediments from the mainland, the barrier islands developed. Various plant seeds carried by water and birds settled into the sand and sediment, producing what would become the “native” plants and trees found today on barrier island dunes, higher ridges and western marshes.

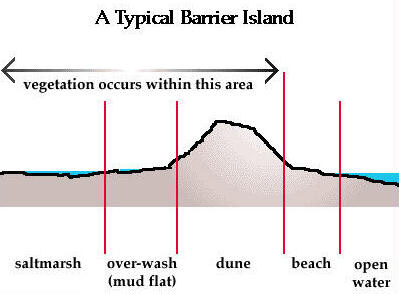

Barrier islands serve two important functions. They protect coastlines from severe storm damage. And the harbor several wildlife habitats. Looking at them from the ocean on the east to the shallow water separating the mainland on the west, they typically have four distinct zones, or habitats, each with its own conditions and wildlife.

The beach zone lacks fresh water but most of it gets covered almost entirely with salt water twice a day by the ocean’s salt water during high tides. Animals and plants in this environment, called the intertidal zone, must survive long periods of salt water followed by exposure to sun and air. Except for plants far up the beach close to the dunes, the only plant life in the beach zone may be algae that get washed ashore. Animals on the beach include clams, crabs and various shorebirds, such as sandpipers, terns, and gulls. Three species of sea turtles (loggerhead, green, leatherback) use the beach zone for nesting during the warm months of May through October.

The raised dune zone, composed of sand and sediment deposited over thousands of years, is the area where most of housing occurs. It has a variety of plants ranging from grasses (bitter panic grass, muhley grass and sea oats), wildflowers (beach morning glory, dune sunflowers and prickly pear cactus), palms (cabbage palm, green saw palmetto and silver saw palmetto), shrubs (cat’s claw, inkberry and Spanish bayonet), and trees (mahogany, southern red cedar and sea grape). All of these plants require fresh water, which they obtain from Florida’s copious rainfall. Because of their location near the ocean, they are salt-tolerant and able to extend roots deep into the dune for stability and nutrient sourcing.

The dune zone also has a variety of interesting animal life, including crabs, ants, snakes, spiders, gopher tortoises, opossum, raccoons, and birds. Almost all of the residential and commercial construction on a barrier island is in the dune zone.

The next zone is the barrier-flat habitat, where the vegetation consists mostly of cordgrass and sawgrass, with some shrubs and small trees. Parts of these areas often flood daily during high tides, so the environment there is mud and sediment full of anaerobic bacteria which decompose organic material from dead plants and animals. Animals in this zone include clams, mussels, snails, crabs, birds, and fish. Gulls, pelicans and egrets are plentiful because of the abundance of food sources.

The fourth zone is the salt marsh habitat found along the shallow water which separates the island from the mainland. Because of tidal changes, this area is flooded with seawater during high tide, thus making it similar to the barrier flats in animals and plants. While this zone may have some residential development, it presents a challenging environment because of it wetness and unpleasant odors produced by decaying plant and animal matter.

While barrier islands protect mainland Florida from the ravages of ocean winds and water, they remain extremely vulnerable to those very same natural forces, as shown by the dune erosion in south Flagler Beach and dune overwash by Tropical Storm Fay in 2008 at Summer Haven in St. Johns County. It is obvious to even the casual observer that, if the islands are vulnerable, then so is everything on them, including homes, businesses and government infrastructure. Because of this delicate balance, it is important for government leaders and residents to understand the dynamics of barrier islands in order to plan and manage effectively, thereby protecting both nature and society.

While barrier islands have existed for thousands of years, what exists today is far different that what may have existed years ago. As in all things in nature, there is a natural ebb and flow, a balance brought about by the powerful forces of oceans, winds, and rain. Historically, this has meant that barrier islands have increased and decreased in their size, shape and composition.

What the future holds for the islands is anyone’s guess, including top scientists from a variety of related fields. As seen when tropical storms pass or nor’easters sit for days, pummeling the shoreline with relentless waves, higher tides, and torrential rains, barrier islands change in more than subtle ways. Beach heights and widths diminish, ocean-facing dunes retreat as the sand is devoured by ravaging seas and stormwater overflowing nearby roads, such as A1A. Flooding from high rain volumes of 18 inches or more, or from Intracoastal waters backing into salt marches and barrier-flats, makes travel for some difficult, if not impossible.

Will barrier islands succumb to the whims of nature? No one knows, nor can it be predicted with any sense of certainty. Does anyone care? Probably those, like my wife and I, who live along the coast on a barrier island. But do others? That’s to be determined by decisions made in the future about how the barrier islands are respected for their unique character and natural wonder. I plan to be an influencing part in those life decisions, not just because those decisions will affect our lives, but because they will affect the lives of thousands, and the barrier islands I love.

Perhaps, as a result of reading this column, you’ll visit a barrier island near where you live. If you do, take the time to enjoy all the natural wonders you’ll find and then lend a hand to preserve and protect them.

Until next week, be well and take one step to help nature.

![]()

Frank Gromling is the owner of Ocean Publishing in Flagler Beach. Reach him by email here.

Kim says

As a non native to FL who bears the last name of Saltmarsh, I found your article to be very informative. I hope that many, many people care about the future of barrier islands and the organisms that call them home. I enjoy your articles and look forward to more.

palmcoastpioneers says

Palm Coasts’ Beachfront – Dr. Per Bruun, Technical University of Norway at Trondheim.

1972, Dr. J. Norman Young, ‘ …An Approach to a New City: Palm Coast..’

Page 128

What follows is of necessity an all too brief discussioni of an approach to a new city. The brevity is unfortunate considering the scores of thousands of words appearing in out technical studies. It is our hope that the reader will gain at least a few insights into our thinking, our philogophy, our science. We only ask him to keep in mind the alternative to what we are doing with our land. It, as is certain with land ownership, our land has been sold to independent subdividers, each of whom built a fifty unit subdivision ( moe than the average builder in the U.S.) there would arise at the very least 5,000 different subdivisions– unplanned, unintegrated, uncoordinated, and without all our controls. Such an eventuality would clearly be unacceptable …typical of the American tragic city-building past. There is another alternative, to be sure. Do not build at all; but then how would the necessity of shelter be provided for the expanding population? In a book published recently, Housing Crisis, U.S.A. 1 ) P. Fried estimates that in a ten year period in the United States in order to replace inadequate housing and build the new housing needed by our expanding population, some thirty-one million new units are required. We estimate that less than two-thirds of that requirement will indeed be built. Worse. What happens later? Do we not build at all? One might as well prepare a dirge for America’s funeral.

Palm Coast will be neither a “sudden city’ nor an ‘instant’ one but will grow in accordance with a pre-planned program, no matter whether it flourishes twenty, thirty, or forty years from now. Palm Coast is a strip of land thirty miles long at its longest, ten miles wide at its widest, covering approximately 160 square miles. It is a fact that under the controls we will institute, despite its being larger in extent than Detroit or Philadelphia, it will have a density of say, Beverly Hills, California. But more on this later. Palm Coast has about six miles of ocean front, approximately twenty miles on the Intracoastal Waterway, and will have significant man made water areas. Again, these will be reviewed in the main body of the text.

Now to a brief description of the terrain. Like other areas along the east coast of Florida, the property was formed primarily by sand dunes that have been build up by the interaction of winds, waves, tidal cycles, and ocean currents. This continued accretion of land as a repetitive process has caused the creation of lagoons between the new dune and the existing land mass. It is from these lagoon that the present salt water lagoons and marshlands evolved.

Page 129

The humps and hollows formed by the repetition of this process have been smoothed over the centuries by erosion and deposition. The resultant ridges and depressed areas are the primary topographic features of this site, with the ridges generall supporting a xerophyric plant community and the depressions supporting a “Wet” plant community.

The types of vegetation on the site, include several ecological plant zones. The MARSH zone contains primarily grasses which are salt-tolerant due to tidal fluctuations and includes salt marsh grass. Along the MARSH EDGE can be found cabbage palms, southern red cedars, yaupaan, and mangrove. The BEACH SCRUB and BEACH HARDWOOD zones are further inland and contain live oak, hickory, southern magnolia, and sweet gum. The significant aspect of these zones is the defensive line of trees protecting the entire area. The UPLAND DEPRESSION zone is between two ridges or within stream courses, and the marginal areas of these stream courses form the BOTTOMLAND and HARDWOOD zones. These area contain ash, sweet bay and water oak, mainly in the former zone, and live oak and cabbage palm in the latter. the CYPRESS classification is not really a zone but a series of irregularly occurring depressions with magnificent cypress trees as the dominant species. The UPLAND HARDWOOD zone contains both natural pine vegatation and ocmmercial pine plantation.

The eleveation on the site varies from sea level to forty feet above sea level. The slope of the land is toward the sea but because of the ridge lines, the natural drainage moves in a north south direction until it reaches a natural outlet to the sea. Because of this circuitous route, drainage is naturally slow and remains on the land percolating downward through the sand and shell deposits recharging the groundwater table below. Given this piece of land we proceed to technical management of our environment and ecology.

Bio-Physical Environment and Pollution Control

Issues of environment and ecology have captured the interest of government, industry, and most importantly, the public. Mirroring this concern for environmental quality, Palm Coast has committed major efforts toward preserving or enhancing the balance of nature in the planning and development of a future city for 750,000 people. The issue at hand can be simply stated: is it possible to have environment and development as complementary, parrallel objectives, or are they mutually antagonistic to each other?

Preservaton of Palm Coasts’ Tidal Wetlands:

Page 136

H. Preservation of Tidal Wetlands

Study: Preliminary site analysis data showed that approximately 4,000 acres of project property are tidal wetlands, which comprise areas of great biological diversity and productivity. These areas produce a wide variety of living organisms, from microscopic species to fish and shellfish, birds, and mammals. Many species spend their entire life cycles in tidal wetlands, whereas others spend portions of their cycles there. Abundant species of plant growth, which form the base for all animal life, are also evident.

Solution: NO building, construction, or development will occur on tidal wetlands.

1. Preservation of Intracoastal Waterway Water Quality.

Study: Available engineering studies, reports, and other records were gathered on the Intracoastal Waterway in the vicinity of Palm Coast , relating to construction problems, erosion, and maintenance-

Page 137

dredging required within the waterway. Also, conditions of the waterway withing the Project tract, information on spoil easements and data relative to flood elevation were documented in the report.

Solution: Earth plugs are used to prevent intrusion of sediment into the Waterway while canal construction is in progress. After turbidity levels in the canals subside to low background levels, the plugs are removed, leaving no adverse effects upon the water quality.

Palm Coasts’ Beach and Sand Dune Preservaton:

Page 138

L. Beach and Sand Dune Preservation

Studies: Historical records of the tide information regarding hurricanes and northeast storms were accumulated. Historiclal Beach dynamics were summarized, isolating the littoral drift, which apparently is to the south during most of the year and to the north during the summer. These data indicate that at Matanzas Inlet there is considerable drift into the waterway. Accompanying this report are the records on what happened at St Augustine Beach and Crescent Beach during the Hurricane Dora, along with storm winde and swell diagrams obtained from the Corps of Engineers.

Solutions. Minimum building elevations were set based on the data obtained. Aerial photogrpahs taken in 1943 were compared with current photographs to determine the amount of beach erosion in this area. ——-> Dr. Per Bruun of the Technical University of Norway , at Trondheim, was retained to coordinate this data and to make recommendations for construction in beachfront areas. Efforts will be made to preserve and protect existing sand dunes. Indiscriminate construction will be precluded by setting all structures back at prescribed limits. Recreational activities on the dunes will be monitored to insure that vegetative systems are preserved.<———-

tulip says

What a very interesting and educational article. I enjoyed reading it and learned a few things. Mother Nature has a reason for everything and we must be careful with them.

Frances says

Excellent article. Always nice to hear from a well informed person who loves our barrier island.

John Smith says

This is EXACTLY why The movement by the infamous group here in Flagler Beach to get the signs removed from A1A for beautification is just another one of there idiotic thoughts. If they remove the signs at the walkovers to the beach and let people park on them and the will SOUTH A1A will look just like NORTH A1A with the dunes worn down open to the sea for erosion. As far as the beach just let mother nature rebuild it and save the money because she will just take what she wants anyway and leave the rest.

Liana G says

Beautiful article. Thanks for adding the pictures too. I was always curious about what lay beyond the islands across from Washington Oaks Garden. I do wish there is a way to restrict the size of the boats that come through. The water is always so oily and trashy.

When I was little we lived on a quaint little island shortly after we lost our dad. My best childhood memories are of life on that island. All the homes were built close to the river/beach and the inner land was used for farming. There was a unpaved road that stretched from one end to the other, and a main trench that ran right alongside. The trench (wider than some parts of the Chattahoochee river) with its little side trenches, was used by the farmers to get to their farms. I remember one of the island laws was not being allowed to use an outboard motor on your boat when using the trenches. Use of an outboard motor was only allowed on the river. The trench also had outlets to the river by way of kokers. Living on that island taught me how to plant, raise livestock, fish, swim, paddle a boat, fire up an outboard engine, climb trees, paly cricked and soccer on sandbanks and so much more. I sat in a classroom that looked out at the river, and went to bed and woke up to a view of the river. The good life……for me.

I wonder who among our local politicans are concerned about our environment. This is a major election year.