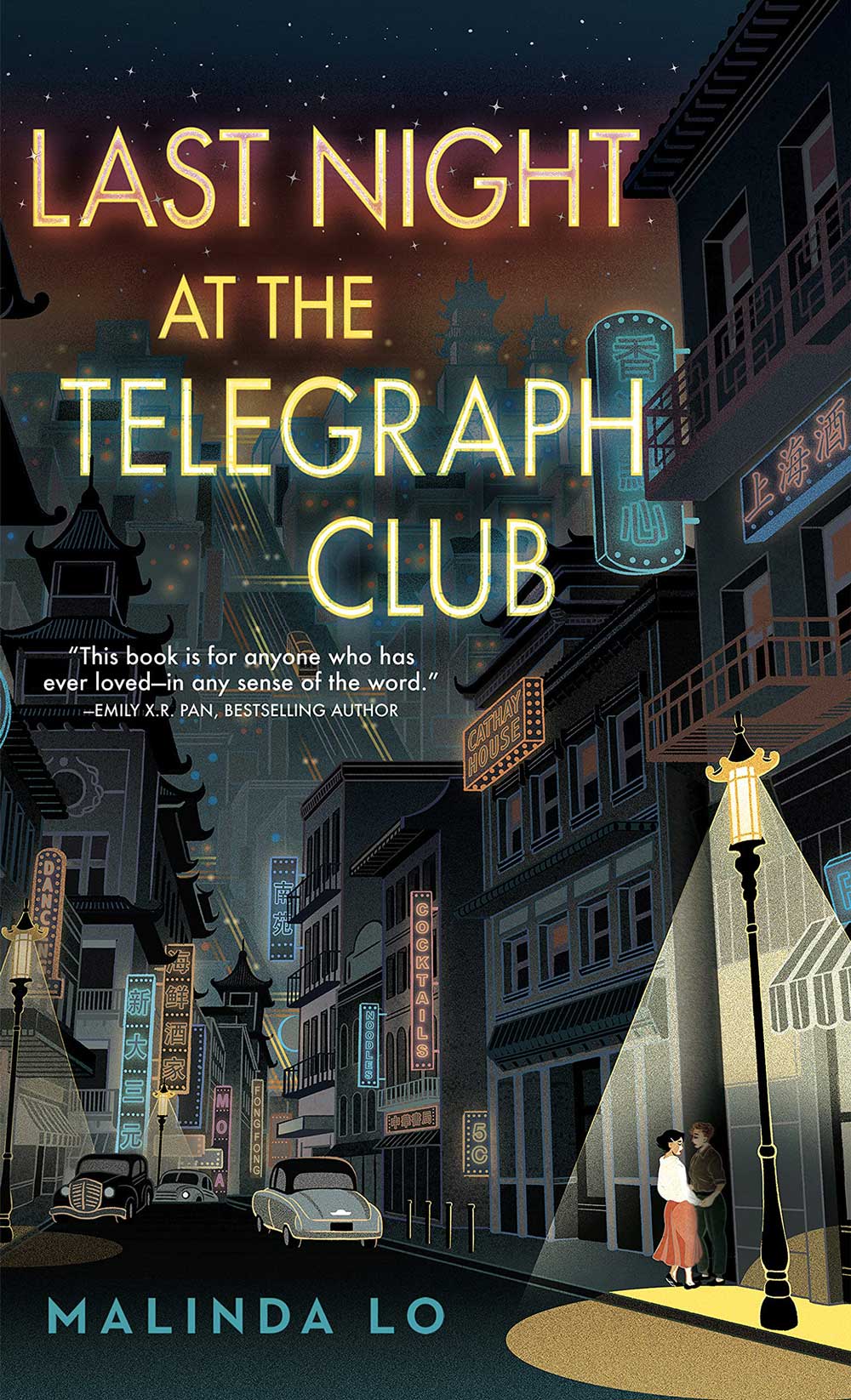

Malinda Lo’s “Last Night at the Telegraph Club“ (Dutton Books/Random House, 2021) is among the 22 books so far this school year that a trio of individuals have sought to ban from high school library shelves. A joint committee of Flagler Palm Coast and Matanzas high school faculty members and parent representatives meets on March 7 at 3 p.m. at Matanzas High School to discuss “Last Night at the Telegraph Club” and decide whether to retain it or ban it. (The committee last met on Feb. 17 and voted to retain Dean Atta’s “The Black Flamingo.”) The meeting, open to the public but not to public participation, is at the Government Services Building, 1769 East Moody Boulevard, Bunnell, in Room 3A on the third floor. The following review by FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam is presented as a guide.

![]()

We think of homeless children as victims of their parents’ hardships. We rarely think parents can be the willing cause of their children’s homelessness. Malinda Lo’s Last Night at the Telegraph Club dispels that hearthy bias and upends the current rage, at least in some developmentally impaired states like Florida and Arkansas, for “parental rights.”

We think of homeless children as victims of their parents’ hardships. We rarely think parents can be the willing cause of their children’s homelessness. Malinda Lo’s Last Night at the Telegraph Club dispels that hearthy bias and upends the current rage, at least in some developmentally impaired states like Florida and Arkansas, for “parental rights.”

The toxicity of parents against any transgression from sexual convention in 1950s San Francisco mirrors the McCarthyism of the period in this historical novel, winner of the 2021 National Book Award for young adult fiction. Not just parents: family members, friends, classmates, neighborhood all collude in a crucible of persecution. Instead of alleged communist sympathizers getting fired, blacklisted or deported, children are removed from their school, expelled from their families and exiled like criminals, for no other reason than because they’re not dating the right sex.

That sort of parent would like nothing better than to have this novel banned. It unravels their playbook: cruelty and ignorance masquerading as love and tradition. You can hear the book-burners say it: “This is for your own good,” the very phrase Lily’s father uses in the book to justify why he’s throwing his daughter out of her home, away from her two younger brothers, her school and a lifetime in Chinatown. “There are no homosexuals in this family,” her mother had spat at her (a kin of the phrase President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran had used about his entire country in 2007), before delivering the ultimate rejection: “Are you my daughter?”

The novel’s 400 pages very slowly weave the web that leads to Lili’s expulsion. After a brief stint as a runaway, when her inclination for a girl–her crime against humanity–is found out, Lily won’t be quite homeless. She’ll be an aunt’s ward 400 miles away. “You’ll be safe in Pasadena,” her father tells her, “while things settle down.” If it’s not homelessness, it’s at least a form of internment. If by then, despite the book’s many ponderous weaknesses, the reader isn’t in revolt at the fate of this gentlest nuclei of dignity and promise–the kind of girl that could lift, say, the entirety of a high school’s grade from mediocrity–that reader, a ticking bomb, might want to check in with a therapist who specializes in latency.

Lily Hu is a bright, 17-year-old high school student engrossed in what we would today call STEM education. She wants to do everything to escape the oppressive gravity around her: her eyes are on rocketry and space exploration. She’s a “good Chinese girl” in a well-to-do home of first-generation immigrants who’ve done very well for themselves. Her father is a physician. He got his citizenship after serving in the Army during World War II despite a version of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act that wasn’t repealed until 1943. Her mother is a nurse.

Lily’s best-friend Shirley is the perfect daughter of parents running a Chinatown restaurant, another “good Chinese girl” who can’t wait to turn herself in to what Betty Friedan a decade later would call the “comfortable concentration camp” of housewifery. (“Good Chinese girl” by the end of the novel has the same atomic weight of smuttiness as “China doll,” the slur we read a half dozen times along Lily’s journey, smuttier than any of the few sexual scenes.) “This is my last year of freedom, and I’m going to make it one to remember,” Shirley tells Lily. “Let’s do this together.”

Instead, Lily transgresses. She isn’t a communist sympathizer. But she might as well be. She gradually discovers that she’s a homosexual before knowing the word or stumbling over its syllables’ tocsin-like denunciations: “Why did it have to sound so obscene, Lily thought, the x crushed wetly in the back of her mouth.” Note the author’s clever, subtle reversion of the homophobes’ favorite condemnation of gays “cramming their sexuality down our throat.” Of course it’s the hetero world that crams its sexuality down everyone’s throat to the point of choking the transgressors, often literally.

This was a time when, as David Halberstam notes in The Fifties, even Alfred Kinsley, the sexologist who did so much to open America’s closets, “could not bring himself to actually write the word homosexual,” when even Reinhold Niebuhr, that great humanist, had Ahmadinejadian tendencies, and when homosexuality was considered a mental deficiency. It was not until 1973 that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses. That’s well known. Less well known is the association maintaining “sexual orientation disturbance” as cause for treatment, defining the “disturbance” as people “who are either disturbed by, in conflict with, or wish to change their sexual orientation.” In Last Night at the Telegraph Club, Lily’s physician father refers to the “disturbance” as “a phase.” In places like Florida today, the “disturbance” gives cover to the state’s treatment bans for trans youth and the more evangelical crusades of conversion therapy.

Communist. Homosexual. Deviant. Pervert. The words in the 1950s of The Telegraph Club were as interchangeable in FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s private memos as they were publicly, in an inquisitorial press exemplified by the likes of Walter Winchell and Whittaker Chambers (the son of an alcoholic who left his home for a homosexual lover). The Chinatown of San Francisco Lo describes was hyper-conservative by necessity, its events, like the beauty pagent Shirley and Lily enter, tailored to win the approval of the business community and that of white Americans by adopting American rituals, however reinforcing of the “China doll” stereotype.

It was also a target of anti-Communist suspicions. Lily’s father refuses to denounce a young man who turns out to be Shirley’s boyfriend, and who had attended a communist-sympathizing rally. But fearing that his citizenship would be revoked if his daughter’s deviance is found out (“Her behavior could further endanger him with the immigration authorities because it reflected poorly on him”), he has no problem exiling her–in essence, denouncing her to his family and community.

In contrast, Lily refuses to denounce Kath–Kathleen Miller–the girl in her senior class she falls in love with and with whom she discovers the Telegraph Club of the title, what would be referred today as a gay bar.

It is there, with a fake ID Kath makes for her, that Lily discover the underground of women impersonating men and women loving women. It is with Kath that she discovers her incompatibility with Shirley, and through those trips to the club and her closeness with Kath that she realizes how jealous, domineering and conventionally intolerant her friend Shirley is. “It’s disgusting,” Shirley tells Lily when Lily refuses to deny her sexuality, as Shirley all but begged her to. “But you can fight it. Don’t let this ruin your life. Kathleen Miller’s out of the picture now that she’s been arrested—thank God for that—but you need to admit to your mistakes. Maybe it’s not too late for you and Will. I can talk to him.” Will is the boy Shirley has been trying to hook to Lily. The scene takes place after cops raided the Telegraph Club and accused its owner of luring girls there to turn them into lesbians.

The novel’s two poles stretch the tensions between Lily and her family, her friend and her community at one end–tensions that slowly constrict around Lilly as if she were a fish in a gillnet–and the contrasting, tender tensions of Lily’s emerging romance with Kath. The demarcation line is literal. It is the boundary of Chinatown. The moment Lily steps in there, she must conform. The moment she steps out and into the Telegraph Club, or into Kath’s embrace, she’s in orbit.

Lo builds the tension at both ends despite the crushing predictability and earnestness of the novel. The details of (platonic) tryst after tryst between Lily and Kath become a chronicle of the thieves-in-the-night dissimulations necessary to carve out intimate moments as no teens would need to if they stuck to binary rutting, in the backseat of their daddy’s Chevy, at Inspiration Points duly recognized by the prom police and the Chamber of Commerce.

There are sex scenes, or more accurately, sexually suggestive scenes. Five, by my count of red-lighted margins. The first is of Lily reading one of those train-station pulp novels of the era featuring lesbians who always end up thoroughly punished, defeated, killed or cured at the end. (That was the deal with the censors, or the books would be considered in violation of obscenity laws.) Lily browses The Castle of Blood with its cover “on which the blonde’s red gown seemed about to slip off her substantial bosom, nipples straining against the thin fabric.” Lily goes back day after day to read at the Thrifty convenience store rack. What we male mutts call a girl-girl scene (“such is the absurd language of imperious man,” in Edward Gibbon’s words) is her first awakening: “‘Kiss me now,’ Patrice whispered. Maxine obeyed, and the sensation of Patrice’s mouth against hers was a delight far beyond shame.”

Lily is not disgusted: “She should feel dirtied by reading it; she should feel guilty for being thrilled by it. The problem was, she didn’t. She felt as if she had finally cracked the last part of a code she had been puzzling over for so long that she couldn’t remember when she had started deciphering it. She felt exhilarated.” Much further on there’s a faint glimpse of “youthfully firm breasts” during a flashback scene attributed to Lily’s father’s memory.

It’s not until the last third of the book that it might give Flagler County’s Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice reason to rouse, and even then, not quite to half mast. There’s an almost creepy scene where Tommy, the male impersonator who plays a recurring role in the book, has “her fingertips softly pressing against [Lily’s] neck, her thumb running lightly but deliberately over her mouth.” The touching doesn’t go further than that, though the passage’s charged implications do. Tommy remarks about Lily being under age. Nothing happens: a skilled writer, like a painter, knows that absence–the suggestive space, the gap unclosed between characters fully clothed–can be far more erotic than anything explicit.

Lo repeats the feat in the fourth passage, the first where Lily and Lo kiss, anatomizing the unbearable fear and relief of the moment (“Her mouth questioned her with each kiss: Is this what you want?”). Lo gets bolder, like her characters, in the final passage, though even there the most the vice squad could complain about is Lily “feeling Kath’s wetness slide against her leg” in the girls’ post-coital embrace.

Not remotely pornographic by any definition (if you’re desperate for an example of actual porn, here’s one from a Thomas Roche story in my copy of Best American Erotica 1999, which tells you how far behind I am), the passage is more a forensic fumble through the terrifying exhilaration of two teens’ self-discoveries in each other. It isn’t without feeling, without that weightless sensuality of the unchartered touch as Lo tries to convey the two girls’ excitement, finally free to go where it will:

Kath hesitated. “Are you sure?” she whispered.

“Please,” Lily said, overcome.So Kath put her hand between Lily’s legs, and Lily helped her, fumbling with her underwear. It was awkward, but when Kath’s fingers touched her, they both gasped.

“Am I in the right place?” Kath asked. “Yes,” Lily whispered. It all felt like the right place. Kath’s fingers rubbed and rubbed, and it was so marvelous, so intoxicating—she’d never even really touched herself like this before—and now she was pinned against the side of the filing cabinet, and it made a dull metallic thud as her hand slapped against it.

“I’m sorry,” she gasped, but she couldn’t really be sorry because it was all happening so quickly, so unexpectedly, and she clutched Kath close to her as the sensations took over, her body shuddering, and she pressed her face into Kath’s neck until it was over.

That’s it. Those 147 words in a 120,000-word book are really why Last Night at the Telegraph Club has ended up on the book-burners’ list, though of course the real reason is because it’s two girls getting it on instead of what Shirley would prefer: Ken and Barbie, not Kath and Lily.

There are problems with the novel. I found it tedious, poorly paced, poorly written and humorless. Characters never just watch each other. They do so “expectantly.” They never laugh. They “burst into laughter.” A “spark of recognition” is accompanied by “a glow of hope.” Nothing is merely alarming, remembered or embarrassing, but always “distinctly alarming,” “distinctly embarrassing,” and so on. (I note the distinct burst of cliches only because I’m in Cliche Anonymous myself and keep falling off the wagon).

The flashbacks to peripheral characters in the novel are pretty much useless, adding neither dramatic tension nor the sort of depth to the characters that might explain their motives or vulnerabilities later on. It’s padding. Nor do the flashbacks give the novel its historical feel. For a National Book Award winner, I was expecting Lo’s 1940s and 50s San Francisco to have at least a little bit of the lived-in realism of Philip Roth’s 1940s Newark in The Plot Against America. But there’s more history in Lo’s Author’s Note than in the novel, and what atmospherics we get from the foggy strolls through Chinatown feel as thin as “the red paper lanterns hanging overhead.” Even Lily is really not that interesting in the end. The sympathy we feel for her is drawn more from context and our anachronistic awareness of the pain children like her endure than from whatever life Lo gives her. For all the boxes she checks in norm-breaking, Lily has none of the charm or surprise, none of the presence of, say, Scott Frank’s Beth Harmon in The Queen’s Gambit. She’s more pawn than queen.

The book award seems to be distinctly applauding its theme, which can’t be under-appreciated. There is very little by way of young-adult literature on the non-binary immigrant experience. I realize that this last sentence, as if written for a critical race theory seminar, can sound alien to literary purpose and atrocious to the anti-woke brigades. They have a point: literature is not a fill-in-the-blanks exercise in identity validation. But nor is literature at heart ever divorced from identity. It was simpler when literature was the product of white hetero male conventions. Identity was monochromatic. Writing from that point of view would have been superfluous. We now know better, and we are better for it.

Its gorgeous, Hopper-like cover by New York-based Chinese illustrator Feifei Ruan and its wonderful dedication aside (“To all the butches and femmes, past, present, and future”), Last Night at the Telegraph Club may fail as literature. But then, so does Tom Wolfe. It doesn’t make either any less readable or, in Lo’s case, usefully so, especially to toxic parents who might learn something about their child, and to young readers desperate for acceptance for who they are–whether they are children of immigrants or not: LGBTQ kids, aliens in their own country, are all migrants waiting for asylum.

![]()

The following questions in bold are reproduced here exactly as they appear on the Flagler County school district’s school-based Review Questionnaire for media advisory committees taking up book challenges–or attempts to ban books–at the school level. Committees fill in their answers as they reach a decision on each challenged book, after a lengthy committee discussion. The answers below are provided as an amendment to the preceding review, in the more focused context of the district’s question, and are of course only the reviewer’s own–in this case, FlaglerLive Editor Pierre Tristam. Committees may reach vastly different conclusions. Those will be appended below, once they are issued.

Title: Last Night at the Telegraph Club

Author or editor: Malinda Lo

Publisher: Dutton Books/Random House

Basis of objection: “Materials contain pornography, Materials are not appropriate for the age of student. This book contains explicit sexual nudity and sexual activities.”

1. What is the purpose, theme or message of the material?

The two themes of the book are the emerging sexuality, as a lesbian, of a Chinese-American girl in her senior year in high school, against McCarthy-era San Francisco, in the first part of the 1950s, when alleged communist sympathizers were denounced. Communist sympathizers had as much sympathy as homosexuals at the time, and both ran the risk of denunciation, ostracism and expulsion from their social circles–if not from the country. The law at the time still forbade entry to “sexual deviants,” including homosexuals. As Erika Lee wrote in America for Americans (2019), “This ban targeting homosexual immigrants would not be lifted until 1990.”

2. Does the material support and/or enrich the curriculum?

Yes. There’s a dearth of books exploring the Chinese-American, or immigrant, experience from the point of view of LGBTQ adolescents, while the McCarthy era seems to be even less understood by adolescents (if not adults) these days: LGBTQ issues are at least discussed in the open, if from instigations of needless controversies and, ironically, the McCarthyist instincts of those persecuting LGBTQ individuals and looking to erase the LGBTQ curriculum. The McCarthyist period in American life, for its part, has been enjoying dormancy in the general curriculum, thus making it easier for current-day McCarthyists to use the same tactics for their purposes. Last Night at the Telegraph Club provides at least the beginning of a historical corrective, though not a particularly powerful one.

3. Does the material stimulate growth in factual knowledge, literary appreciation, aesthetic values, and/or ethical values?

Yes and no. The factual parts of the book appear soundly based in research. Its exploration of individuals’ behavior regarding denunciations of friends and neighbors, whether because they are believed to be communist or gay, is an analysis of individual ethics. Most characters in the book fail the ethical test. Lily, the protagonist, does not. As for literary appreciation: the book, as noted in the review, is competently written, it is accessible even to more advanced middle schoolers who may be tired of the childish tripe in their libraries, but it isn’t literature. It’s good fiction, but in a formulaic, predictable sense.

4. Does the material enable students to make intelligent judgments in their daily lives?

That depends on your perspective. To a dogmatically traditional family, where roles may not be challenged, Lily’s decision to explore her sexuality is a challenge and a transgression as grave as her sexual transgression, and her banishment would be applauded by such traditional–and of course toxic–family members. To the more humane-minded who place individual choice and dignity ahead of traditional dogma, Lily’s exploration is as courageous as her perseverance, until she hits her family’s wall and is exiled. She does not challenge her exile because she does not want to jeopardize her father’s immigration status: that, too, is to her credit. She subsumed her discovery to protect her father, even though her father had refused to protect her.

5. Does the title offer an opportunity to understand more of the human condition?

Yes. It is a painful read. It is yet another chapter in what Philip Roth called “the ecstasy of sanctimony” (in The Human Stain) and what Hawthorne called “the persecuting spirit,” in relation to the Salem witch trials, two references that remind us that America’s persecution of heretics is as old as Plymouth Colony and as still-burning hot as the faggots beneath the DeSantis inquisition’s cauldrons.

6. Does the material offer an opportunity to better understand an appreciate the aspirations, achievements and history of diverse groups of people?

Last Night at th Telegraph Club opens a broad window on the aspirations of one of America’s largest group of immigrants, on the aspirations of adolescent girls who like girls, and on girls and women who thrive as scientists, as Lily’s aunt does (though she thrives less well as an advocate for her niece).

CONTENT

1. Is the content timely and/or relevant?

The content is timely and relevant: the marginalization of non-binary adolescents is a crisis, especially in Florida, the history of the 1950s needs a refresher in young readers’ eyes, and the immigrant experience is with us every day, but too much at a distance. A book like Last Night at the Telegraph Club helps bridge that distance in a non-ideological, non-confrontational way.

2. Is the subject matter of importance to the students served?

That’s a double-edged question. It ought to be a subject matter of importance, even if you take away the Chinese-American or even the lesbian theme: the immigrant experience during the McCarthy era is an original angle. It won’t be a subject matter of importance to most students in Flagler County because our Chinese-American population is limited, and too many students these days have grown up on English teachers’ narcissism-inducing method of reading what they can relate to, as opposed to reading what they may relate to less, in order to better understand “the other.” From that perspective, this book would serve a valuable service.

3. Is the writing of high quality?

No. It is plodding, riddled with extraneous details (do we really need to have so many insights on bathroom experiences? And I don’t mean the sort of tryst that might need a bathroom’s isolation for a tryst), formulaic writing and long, unnecessary flashbacks.

4. Does the material have readability and popular appeal?

The writing is readable. It’s poor, but not offensively so: there’s a degree of restraint and straight-forwardness that serves it well. The book would seem to have limited popular appeal.

5. Does the material come from a reputable publisher/producer?

Yes. Dutton is an imprint of Random House, one of the big American publishing houses.

6. I presented as factual, is the content accurate?

As historical fiction, much of the historical information is in the author’s note. It’s a summary of basic facts about the era. If there are inaccuracies, I did not denote any.

7. If the text is informational, is the text comprehensive?

It’s fiction, so it’s focused on Lily and her family, with a few asides about the broader context. It could and should have been more comprehensive in that regard, cutting out a lot of the extraneous details about some of the characters–and those bathroom trips–in favor of more integrated history.

APPROPRIATENESS

1. Does the material take in consideration the students’ varied interests, abilities and/or maturity levels?

Yes. The book is grounded in the high school experience and would ring true even to those who have not grown up in a large city, in a different decade, as immigrant children, or gay. It does not condescend.

2. Does the material help provide any of the following:

- A resource that represents a level of difficulty accessible to readers at the school?

- Diversity of appeal?

- Representation of diverse points of view?

Yes to all, whether the readers are in high school or middle school (though this is a book targeted at high school readers). It has diversity of appeal, but it is somewhat limited in that regard, the Chinese-American theme being its intentional focus. That does not make it any less comprehensible or valuable to, say, an Eritrean-American or a Floridian from the sort of allegedly traditional family Lily’s parents claim to represent. There are quite a few points of view, but the author’s allegiance is unquestionably to Lily: Shirley, in contrast, is made to look like an annoying, insufferable dimwit, which weakens the novel. It would have been more persuasive if Lily’s best friend had an equally strong character all around, even if she is a bigot.

3. Does the material help to provide representation for various religious, ethnic, and/or cultural groups and the contribution of these groups to American heritage?

A big yes regarding the Chinese-American contribution to American culture, which has been and continues to be immense, though that awareness tends to be more distant from students in Florida, at least in comparison with students on the West Coast.

4. Does this material provide representation to students based on race, color, religion, sex, gender, age, marital status, sexual orientation, disability, political or religious beliefs, national or ethnic origin, or genetic information?

Race, sex, gender, marital status, sexual orientation, national origin, yes. The rest, no. Political beliefs are touched upon, to reflect Lily’s family’s conventionally conservative outlook and support for nationalist China, though it’s never clear whether her father was an Eisenhower man or an Adlai Stevenson man. It is unlikely he was the latter (against whom Hoover’s FBI spread the false rumor that he was a homosexual).

5. In a Yes or No answer only, do you feel the material has a purpose for a school library collection?

Yes.

Comments specific to the objection: The objection suggests that the objector have not read the book, do not understand the meaning of “pornography,” or do not have a grasp of the English language, elementary as Lo’s writing happens to be.

Additional comments: For all my criticism of this book on its literary and formal merits, I am glad I read the book, not just because I had to review it, but for its sake: as an immersion in an experience and a point of view I know too little about, and am grateful to have learned a lot about. I may be a first-generation immigrant. But that’s not a monolithic experience. To focus on one’s own is as reductive as embracing the more conventional prejudices that continue to make it difficult for people Lily represents to have their place in the world, with all the dignity and equal rights the rest of us enjoy.

Recommendation (retain, remove, other): Retain in high school. Would not be out of place in middle school, for more advanced readers.

![]()

Laurel says

I think the Mommies for Illiteracy should read George Orwell’s “Animal Farm.” They should be able to make it from cover to cover. Then again, it might hurt their feelings.

The dude says

They don’t actually read these books at all.

They come in a list from various rightwing jackassery “think tanks”, along with urgent pleas for $$$, and the crazy loons comply.

Local says

They are not moms for illiteracy…. It’s people like you that change the facts to prove a made up political point. It’s the same as the “don’t say gay “bill and racism.

Laurel says

Local: These three self important individuals are against literature, which I would wager you that they have not read themselves, much of which has been proven great literature. They are not for liberty, they are pretending to be big fish in a little bowl and having a good time with themselves. I would hope you do not listen to their crusade for censorship.

Please read “Fahrenheit 451,” by Ray Bradbury.

It’s *people like me* who see though these three. No facts were changed here, just sarcasm. Do you not see the difference? People are not allowed to have intellectual discussions about LBGTQ+ life, hence the “don’t say gay” sarcasm.

This Is A Wonderful Book says

I find it amazing people think this isn’t appropriate for older age groups. Newsflash – teenagers have sex, they pass on STD’s to one another, they get pregnant, and many do these things without being properly educated how to have safe sex.

Some states even allow for gross old men to marry girls as young as 12 or 13 but there is nary a peep from these groups about how that is the antithesis of protecting our children (hint: because it’s hetero).

There is nothing wrong with this book. Not one thing except for the usual panic defense – but it’s GAYYYYYYYY. And? So what? You don’t wake up at 18 and have an epiphany, shouting toward the sky that you like someone of the same sex. No, you know very early on, same as hetero people. I doubt any of you straights discovered you liked the opposite sex at 18. I’m sure you were 8, 9, 10…same for LGBTQ kids. All this does is make them feel like they don’t belong. You take away someone that looks like them and they can’t talk to people about how they feel or what they feel, they can’t go to dances with the people they want, they can’t date the people they really like, instead they hide, they pretend, and they’re miserable.

Maybe that’s ok so YOU don’t have to deal with it, but imagine for one second you weren’t accepted for loving someone of the opposite sex, or you were ostracized for being hetero, or bullied and beat up or even killed because you (a man) loved a woman, or vice versa. Imagine that for just one second. All books that show hetero relationships removed and banned, no teacher can discuss any kind of relationships they’ve seen in the hetero community that relates to the students (such as a student’s parents), and the kids of those heteros, the torture would be endless. Imagine your safe spaces eliminated. Imagine your existence threatened. Imagine faking who you are in order to life more more day without fear of being persecuted.

I know that will never happen and all you heteros should take a deep breath and huge sigh of relief that you weren’t born LGBTQ so you’ll never know what it’s like to have someone hate you just for being you, how the creator created you. You will never have a parent threaten to kill you because you love someone of the same sec. You will never be gang raped because someone wants to convert you to heterosexuality. You will never be groped and checked if you’re a girl or not. You will never fear for your life when you see a group of people walking menacingly toward you when you’re all alone. You will never be mercilessly beaten just because you’re LGBTQ. Take that breath and appreciate yourself being able to always live as you were born, unlike many LGBTQ kids that are kicked out of their homes, forced to live on the streets, and punished just for trying their live their true selves, just like you.

Denali says

Pierre, I am afraid you have really stepped in it this time. You have written what needed to be said; even I, an old, fat, white guy am thinking that I should read this book. My high school years were spent in a liberal bastion of the Lilly white northern suburbs of Chicago. Rumbles of McCarthyism were still vibrating throughout the community and even though the sexual revolution was at our doorstep and given our liberal surroundings, the word homosexual sent shivers down the spines of every WASP parent. My graduating class was over 600 and we had a few of “them” in our class. We were the last of the Good (the Preppies), the Bad (the Greasers) and the Rah-Rahs (those who lived for the Friday night pep-rallies). “They” were a part of each mentioned group, “They”fit in with most everyone except for those few troglodytes in our class. “They” were always ready with help in a class, a joke or some earth-shaking platitude. “They” were banned from prom, we threatened an empty ballroom and they faculty saw the light. “They” were our friends.

The only problem in our community was our damned parents. “You aren’t talking to that Susie or Bobby are you?” Guess they were afraid we would catch whatever it was that made Susie and Bobby sick. I never caught whatever that dreaded disease was and have remained friends with a Susie or Bobby for most of my life. It’s pushing 60 years since I was in high school; I would have thought that by now we would have learned to live together and had come to understand that each of us, even “them”, had a role to play in our world. Then again, I hoped that Jim Crowe had died a miserable death and relegated to the trash heap of history.

My fear is that those who need to read/comprehend both the book and your critique will not and that they will continue to spew the vile and hatred which has consumed them for most of their existence.

Steve says

I don’t believe mom’s for liberty or any group should ever have the right to tell anyone other than themselves and their minor children they can’t read a book. If they object to the content, then they should monitor their own children’s reading habits and leave other parents to make their own decisions on their child’s reading choices. The idea that because they don’t want their child to read something means that your child is also forbidden is just totally against any concept of liberty and freedom. Giving in to these people is just another step closer to a theocratic fascist society.

Michael Cocchiola says

Moms for Lunacy are flat-out liars. In the most recent school board meeting, I spoke of attempts to ban books that are considered wonderful literature. I said some elements in our community are trying to limit the knowledge of our students (“dumb down”) by banning books they hate… books written by gays and Blacks. I called those “elements” insidious and bent on degrading public schools.

A mom for liberty spoke next and declared loudly that they don’t ban books. That’s a lie… a big one. The state has caved under pressure from these extremist “moms” and has banned books, and books are being banned throughout the Florida public school system. The moms for lunacy – a sexually repressed fringe group of Christian nationalists – are trying to force their repressions and beliefs on all students. That’s what has happened to the “liberty” in their original name.

We have an existential fight on our hands. Is our school system going to be knowledge-based or White Christian culture based? Will our students be able to compete in a highly educated marketplace or will they work at Chick-fil-A where their bible training counts for something?

The moms for lunacy are a threat to public education and we need to recognize that.

Local says

This is exactly what the government wants….People arguing. They are running out of race issues because racism is almost dead so now they are jumping right on the lbgtqrs train and y’all jump right on with them. It both sides Democrats and republicans that work together to come up with ways to divide us.

United we stand

Divided we fall

The dude says

Racism is nowhere near “dead”.

It is alive and well in many many places across this country. Especially here in the dirty south.

SCOTCHWORKS says

I was a voracious reader in my childhood( I’m 58). I read everything and anything I could get my hands on. I had bookshelves in my bedroom stacked with “The Hardy Boys” , “Encyclopedia Britannica” , History books and all manner of literature forwarded to me by my Aunt (HS AP English teacher).

I would venture to say that in most homes today that have school aged children , there is not a bookshelf, there is not a book of any kind to be found in their possession.

I’d wager there are more game titles, electronic devices and DVD’s than books.

Who cares what books are banned or subject to review in our schools?? Nobody reads anymore….you can’t find a bookstore…

I would guess 7/8ths of the books under “review” have never been read much less checked out of any library system.

There is much more sinister content waiting for your children on the internet.

The dude says

YES!!!

I too personally love to hold a book and turn the pages. (Holding a kindle or iPad just isn’t the same)

But times do change and I’m ok with that.

All that being said, the very same internet that brought us “horse dewormer cures COVID”, “Jewish space lasers”, and Qanon is out there patiently waiting to teach our unsupervised children the same “truths” it’s apparently taught our parents and grandparents.

Laurel says

Dude: Qanon wasn’t around when our parents and grandparents were children, hence did not teach them anything like space lasers. We got our shots whether we liked it or not. My mom raised me to be open minded, and straitened me out when I became too judgemental of others.

We recently lost one of our best friends due to cancer. We are now realizing that we are the last of the “hippies.” Our friends were black, white, gay, Christian, atheists, pot smoking, LSD taking, strait laced and any other category one can imagine. This current group of pseudo-Republicans are shocking to us. We’re waiting for them to show up in their white, pointy hoods and gowns.

This hostile takeover of our state, freedoms, liberties, bodies, minds, neighborhoods and schools have to stop, and now. I write my senators, but do not have the lobbying power and money to sway them one inch. We just need to keep voting these people out until they get the message, or better people get in. Unfortunately, they, and Fox Entertainment, keep their followers in the dark, and ignorant of the truth.

Charles Gardner says

Haven’t read the book but did read the review. IMO the sexually suggestive content is no worse than the 23rd chapter of Ezekiel.

Deborah Coffey says

Today’s comments above are all exquisite and spot on. So, I won’t ruin their beautiful stories and opinions by writing what I wish for…for the Moms’ for Liberty children. Let’s just say that some people need to learn how to love…the hard way…trial by fire.

Reader says

This book made me cry in the most beautiful way. As someone who was going through a similar situation with my sexuality, I just loved it so much and it made me realize a lot about myself. I really enjoyed this read, it really opened your eyes to a lot of things. I recommend it to everyone- you don’t have to be LGBTQ+ for this book to have an effect on you… It’s so beautifully written Lo did a great job.