(© FlaglerLive)

| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

The car radio was randomly set to the signal of its choice as I was approaching Rapid City. Garth Brooks sang “The Dance,” Tim McGraw sang “Where the Green Grass Grows” (“I’m gonna live where the green grass grows/Watch my corn pop up in rows/… Point our rockin’ chairs towards the West/And plant our dreams where the peaceful river flows), then the announcer said it was time to join the Lakota Sioux tribal council.

What followed for the next several hours was like any local government meeting. Instead of discussing rezoning a parcel for an apartment complex or finding sand to replenish the beach, the council members agonized over the reservation’s economic depression, the importance of developing native micro-businesses and attracting white tourism dollars that flush through western South Dakota, always skirting the reservation. Crime would come up sooner or later. The Pine Ridge Reservation prison was 350 percent over capacity. Every prison in Indian country was over capacity.

I forget the names I heard. Council records since include the likes of Bernie Shot with Arrow, Stanley Little White Man, Lydia Bear Killer. When I wrote my original story on South Dakota for the newspaper, I thought I was being cute by saying the council members had names out of “Dances with Wolves,” not realizing that I hadn’t been in Indian Country for a paragraph before I began stomping it white, true to type. That’s the Black Hills’s history for the last 200 years: ennobling white theft and exploitation in the exonerating language of fabrication and manifest destiny.

As I drove up toward the Black Hills later, the station’s signal skidded for a minute, then was overwhelmed by a more powerful station’s broadcast of NPR’s “All Things Considered.” It was back to Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky, Microsoft in court, the kidnapping, torture and murder in Wyoming of Matthew Shepard, the 21-year-old gay college student killed for who he was (or for meth, as one revisionist concluded years later). I could have been anywhere in America.

The contrast between Tim McGraw and the tribal council, between the Native American radio station’s signal and National Public Radio’s, was a quick lesson in the cultural contradictions of western South Dakota. For all our unique homogeneity as a nation — there is less ideological and commercial difference between Tallahassee and Juneau, a continent apart, than there is between any two European cities on opposite sides of the same river — we are also a nation of parallel cultures, integrated in fringes more than in fact.

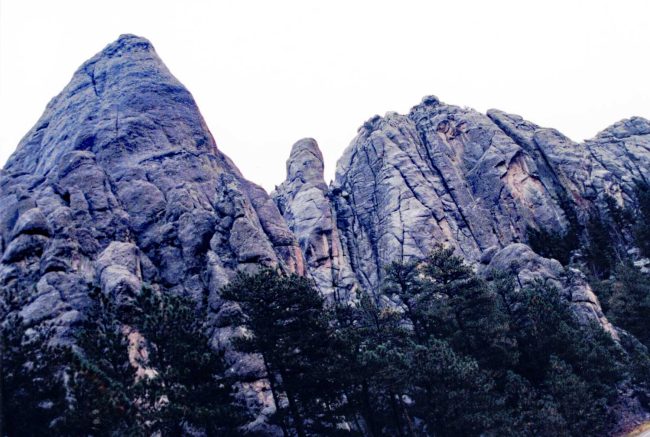

I was drawn to that fringe in the Black Hills, an area the size of Connecticut in the western part of the state the Lakota consider “the heart of everything that is,” and that non-natives have been colonizing with greed and monumental tackiness for almost two centuries.

The Sioux reservations there are remnants of an empire-like nation that extended to the Great Lakes and whose western tribes–the Lakota, as opposed to the eastern Dakota–were the ruthless superpower of the continent, wiping out or dominating other tribes. Bernard DeVoto, the liberal historian of the West who wrote before the era of political correctness, called the Lakota “the true terrorists,” though the white man put their brutality to shame. They’re the only tribe Lewis and Clark feared, the only tribe with whom, thanks mostly to hot-headed Meriwether Lewis, they had a standoff that could have wiped out the expedition but for a benevolent Sioux who blinked on behalf of his tribesmen.

That was when whites, after a non-existence of millennia, were a fringe. Whether the Sioux had been there for millennia is disputed. Revisionist histories backed up by archeology put the Sioux’s arrival in the Black Hills only a few generations before Lewis and Clark, though other tribes had unquestionably been there for thousands of years. Sioux scoff at whites’ attempts to rewrite their history, much like Palestinians scoff at Israeli versions of who was in Palestine first–who belongs, who doesn’t.

To the Sioux, the Black Hills are their origin story, down to their emergence from beneath the hills near today’s Wind Cave National Park around 2,000 years ago. In 1979 Russell Means, the leader of the American Indian Movement who’d led the 71-day armed seizure of Wounded Knee in 1973, called the Black Hills “our graveyard, our church, the center of our universe and the birthplace of our people.” The Black Hills are untouchable, off limits to whites. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie had put that in writing after decades of warfare between invaders and Indians.

With that treaty, Congress set aside an area nearly the size of Wyoming for the “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of Sioux Indians and “other friendly tribes.” No sooner signed than broken. Gold drew in white prospectors and General Armstrong Custer, who terrorized Indians with his Seventh Cavalry until he and his army were surrounded and wiped out at Little Bighorne. (After gold came the digs for uranium.) The invaders’ other massacres, of bison, were more effective in starving out Indians, forcing them onto reservations in droves. The army’s 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee of 300 Lakota Indians, most of them women and children, was My Lai on the Plains. The wars were over.

Then came the monuments.

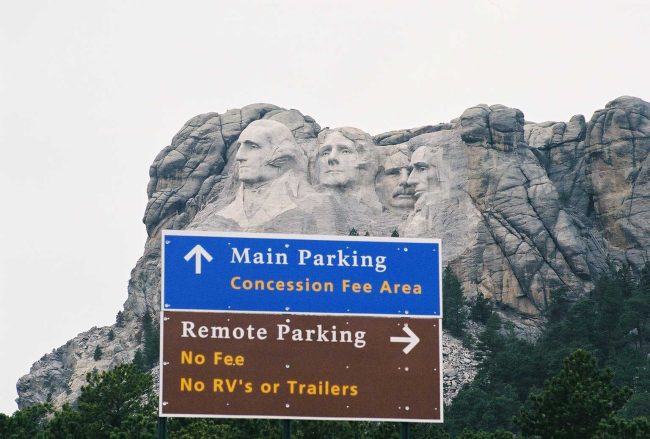

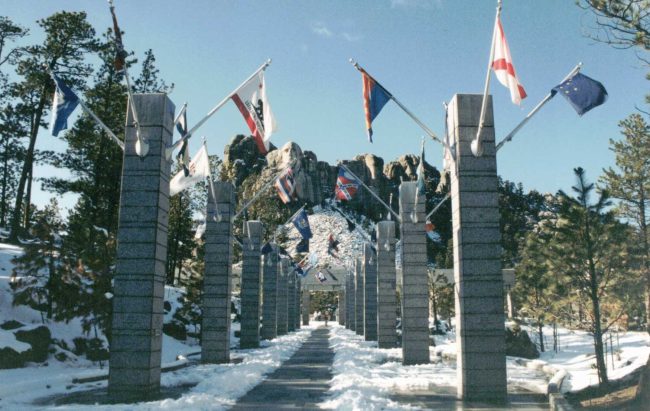

In the eyes of the Sioux, their sacred Black Hills above present-day Rapid City were first desecrated by gold prospectors in the late 1800s, then by the rock sculptures of Mount Rushmore between 1927 and 1941, then by the more swindle-like sculpture of Crazy Horse on a nearby mountain that started in 1948 and looks like it’ll never be finished, and by the millions of tourists who visit either every year, pouring money like gold into hands no less white today than those drilling the mountains in the 19th and 20th centuries. I was no less of a tourist, as was Cheryl, who joined me for a few days on that segment of the trip.

We were among the 2 million visitors who gaped at Rushmore that year (it was up to 2.5 million in 2021). You can’t help it. Majesty and folly are not mutually exclusive. There was majesty to Big Bertha, the 17-inch caliber, 33-foot-long howitzer the Germans rolled out at the beginning of World War I, dropping shells on civilian towns from 75 miles away, just as there was a majesty to the Enola Gay as it dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima and that mushroom cloud–itself majestic, as any nuclear blast seen from afar can be–rose above the 120,000 civilians it murdered. That’s the kind of majesty Mount Rushmore evokes: Awesome, powerful, mesmerizing. But also horrifying.

The work isn’t beautiful. There’s craft, not art, in the sculpting. The four faces are more cadaverous than life-like, giving them the whitewashed look of death-mask plasters. That’s partly by design. Gutzun Borglum, the sculptor, avoided undercuts in the granite to prevent ice buildup that would crack and snap off a nostril here, an eyebrow there. Surely an artist could have done better with 1,000-foot-high gnarls of metamorphic rock. Unless the mountain had other ideas, as it very much seems it did.

The four figures seem more captive of the mountain, more frozen in state, than the princes and kings and queens of the life-like steles of Ancient Egypt, whose presence erases the distance to 2500 BC. The look on the four faces are vapid. They can’t decide what to look at. They’re the uncomfortable, uninvited guests at a party, as if they themselves would ask, perhaps with the exception of Teddy Roosevelt: what on earth took you to put us here? They may be famous. They may be enormous. They may be enormously powerful. But they just don’t belong, and no bigness can compensate. If they loo placid, their presence is no less of a gang rape of the hills.

Jonah Doane Robinson, the South Dakota historian, conceived of Rushmore as a tourist trap in 1923. In 1925 President Coolidge signed “An act authorizing the issuance of patents to the State of South Dakota for park purposes of certain lands within the Custer State Park now claimed under the United States general mining laws, and for other purposes.” The dynamiting could begin.

It is no different than if the government had stolen sacred land, turned it over to Disney, and given the company free reign to build a theme park to four racists there, with a Ku Klux Klan member as its chief architect. Washington and Jefferson owned slaves. Lincoln, who never believed in the equality of races, is responsible for the largest mass executions of Native Americans in the nation’s history. Teddy Roosevelt, who presided over the atrocities and mass killings of the Philippine-American War, had said: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”

That’s what Mount Rushmore is: a theme park to white American supremacy, sculpted by Gutzon Borglum, the man who sat on the KKK’s policy-making “Kloncilium” and who’d first hammered Stone Mountain, Ga., into what would become the nation’s largest celebration of the Confederacy. Each shard of the mountain’s 450,000 tons of rubbled rock is an unmarked tomb for an unconsecrated genocide.

Imagine next if Universal wanted its share of the spoils, got its own acreage of stolen mountain through a mining claim, west of Rushmore, and started dynamiting that mountain to carve an even more massive sculpture, this one ostensibly to honor Native Americans.

Welcome to crazy.

*

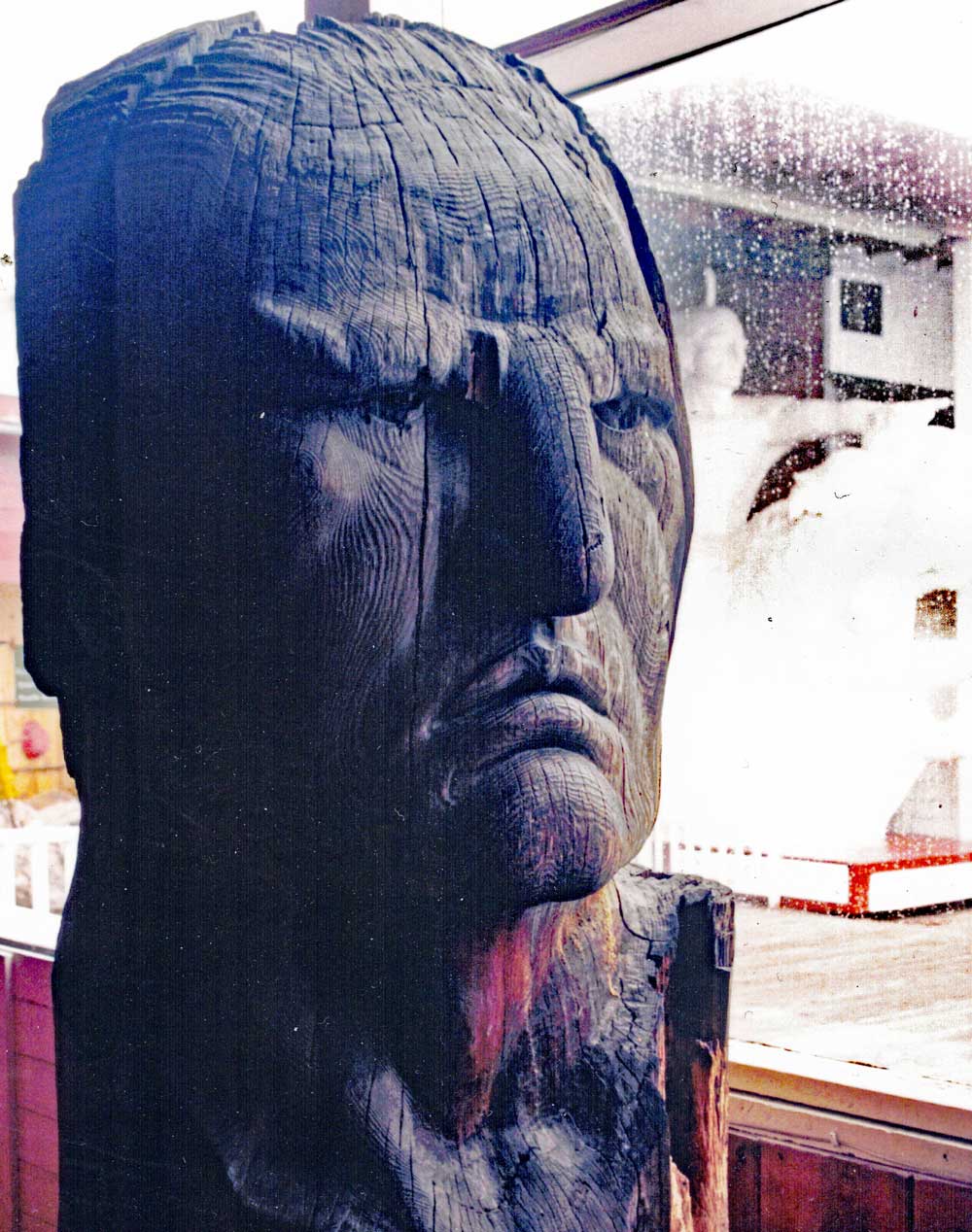

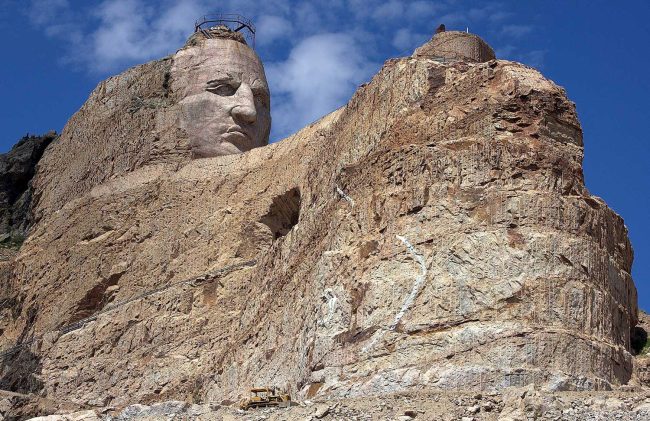

The Crazy Horse Memorial is being carved out of Thunderhead Mountain, 17 miles from Rushmore. When completed in who knows how many years, or rather if, because it doesn’t look as if it’ll ever be completed, it will dwarf Rushmore in size and, I’ve heard it said many times, in popularity. The entire mountain is becoming a 563-foot high sculpture of an Indian on horseback. He is looking and pointing to the east, because when the Indian was derisively asked by a white man, “Where are your lands now?” he pointed and replied, “My lands are where my dead lay buried.” It is not a look of faith but of defiance.

The Indian rising out of the mountain supposedly represents Crazy Horse, the great warrior and tactician, defender of the Great Plains and victor of the Little Bighorne in 1876. A year later Crazy Horse surrendered, vowing never again to fight whites. He was stabbed in the back by a guard in a scuffle at Fort Robinson in Nebraska for refusing to be jailed in a guardhouse. He was barely into his thirties.

The duel of legacies between Mount Rushmore and Crazy Horse Mountain is paradox enough about the parallel cultures of the Black Hills and their sordid history. But Crazy Horse Mountain is itself a paradox. Forgetting Mount Rushmore — as I did during the three days that I spent on Crazy Horse Mountain — the Crazy Horse memorial by itself is as deep a contrast between white and Indian cultures as I encountered. The contrasts are intended to inspire awe and hope, and in some ways I was taken by them. In just as many ways, the contrasts were also exploitative and foreign to the spirit of Tasunke Witko, the man known as Crazy Horse.

Crazy Horse Mountain does not belong to the Sioux, nor to any Native Americans. Not now, anyway. It was originally acquired by the sculptor through a mining claim — the very sort of claim Crazy Horse had waged war against. It’s no less stolen land than Rushmore. The sculpture was not created by an Indian, nor would it ever have been carved by Indians, considering the sacredness of the Black Hills to Native Americans and Crazy Horse’s own prohibition against being pictured or painted, let alone glorified.

The mountain sculpture is the creation of one man: Korczak Ziolkowski (pronounced Core-CHOCK Jewel-CUFF-sky), a Bostonian of Polish descent who worked on the Rushmore presidents for 19 days in 1939, didn’t get along with Borglum (he called him a “pseudo-sculptor” who worked for $1.25 an hour without a day’s work “of any value”) and whose previous works had included plump carvings of Noah Webster, the classical pianist Ignacy Paderewski, and Wild Bill Hicock. A biographical booklet handed out on the mountain tells the story of how Korczak (who is always and everywhere referred to by his symbolically aristocratic first name) became intimate with Indian culture after World War II, how Indians invited him to sculpt Crazy Horse, and how “the old Indians insisted the Memorial be in the Black Hills.”

Like most of the factoids one encounters on the mountain, it is difficult to verify who the “old Indians” were, or how many they were. The plural is probably an exaggeration. Luther Standing Bear, the actor (and Crazy Horse’s brother in law) had tried to convince Borglum to add Crazy Horse alongside the Rushmore presidents. Borglum deflected, vaguely pledging to carve something “where the Eagle rests,” whatever that meant. After Luther died, his brother Henry took up the cause, pitching the proposal to Ziolkowski, giving the letter the weight of Jibril’s revelations to Mohammed on Mount Hira.

“Now this is where I was a sucker,” Ziolkowski told Morley Safer in a 1977 interview for 60 Minutes. “And I’ve never regretted this. I’ll do it all over again. He said, ‘my fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the Red Man had great heroes, too. What’s wrong with that? Where’d I have to go? What was my life? To carve a mountain to a race of people that once lived here for maybe 100, 150,000 years? What an honor.”

The majority of people in and around the Black Hills didn’t take Korczak any more seriously than his habit of compulsive exaggerations. (Modern humans did not leave Africa until about 60,000 years ago, and did not reach the Americas until at most 17,000 years ago, and the landmass now known as the continental United States until much later than that.) Those exaggerations aren’t the charming eccentricities of an artist, like Horowitz’s wrong notes during concerts. They’re tactical. These days they’d be more accurately compared to what Donald Trump called “truthful hyperbole” in The Art of the Deal.

It’s an apt comparison when applied to the business organization built around the Crazy Horse carving, from the exorbitant costs of entry or extra costs of privileged access to the monetizing of every corner of the operation down to selling rocks blown from the mountain–plunder as souvenirs–or the tactless gaudiness of the work itself, which gave me the same initial sensation as the micturating ramparts of pink marble in the atrium of Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue. Korczak acquired the mountain through a mining claim, not for gold–although who knows?–but what he and his family have extracted in profits from it since has far surpassed any valuable ore it might have yielded.

Korczak began working on the mountain by himself in 1948, living sparingly and tirelessly, earning the derision of local Americans, supporting himself by charging visitors 50 cents for admission to his “studio home” and selling wood from the mountain he was slowly acquiring. Married in 1950, father of 10 children, he devoted the rest of his and his family’s life to the sculpture and refused repeated offers by the federal governments to fund the project. He wanted control. He died in 1982, at age 74. He had prepared detailed plans for the mountains, which his wife, Ruth, continued to implement with iron will — and hand.

*

It’s been the story of two mountains since.

One is the story of the sculpture itself taking shape on the section of the mountain called Thunder in the Sky. Only the 87-foot face was finished when I first visited, in 1998, on the sculpture’s 50th anniversary. Only the face is finished today, 24 years later. Then as now, the imagination has to visualize the rest with help from a thick, painted outline of the horse’s head.

The work, rising higher than the highest pyramid or the Washington Monument, is still impressive enough to make you stop and stare for a very long time, even from two miles away. (For safety reasons, visitors are not allowed to get close to the work-site, unless they pay extra.) There’s majesty in the folly here, too. The sculpture wants to radiate the echo of something mighty that once ruled these hills. Does it humble the present and evoke respect for the past, the Native American past, or is the visitor wishing that it did? If I looked only at the mountain, even in incomplete form, I couldn’t help feeling humbled. But for all its mightiness, the sculpture is an optical illusion.

On the ridge below, it’s another story, another world — the world of the Ziolkowski family enterprise, where the main business is not Crazy Horse but a theme park to Korczak, Korczak, and more Korczak.

Like the autobiographical booklet, which reads like the life of a saint shorn of humility, the visitors’ center, the 10-minute slide “orientation” about the mountain, the family’s “studio home,” the “family log home” and the gift shop were a shrine to Korczak’s life and work. I would have liked to come away from the mountain more enlightened about Crazy Horse. I learned nothing about him that I hadn’t learned better and more movingly in very few pages elsewhere. But I came away knowing more than I ever wanted to know about Korczak, a “man of legends, dreams, vision and greatness,” as The Progress, a publication produced on the mountain, described him by means of headlining his eulogy in 1982. From what I’ve read since, the aggrandizing of Korczak has made many more strides than the carving of the mountain.

Even the sculpture on the mountain looked more Korczak than Crazy Horse. Black Elk, a celebrated Oglala Sioux who fought alongside Crazy Horse, once said the warrior was “a small man among the Lakotas and he was slender and had a thin face.” The face on the sculpture, anything but thin, reproduces Korczak’s wide forehead, his large nose, the same creases of his eyes and the same prominent lips. When I brought this up with Korczak’s widow, she said: “That’s your imagination.” But she added, “It’s not a likeness of Crazy Horse. He never meant it to be. It is a symbol.” In other words, truthful hyperbole.

In 2008, when the organization acquired a knife it claimed had belonged to Crazy Horse, an employee questioned the authenticity–just as he questioned that Korczak and Crazy Horse died on the same day, Sept. 5, rather than Crazy Horse’s better documented death on Sept. 6–and was subsequently fired.

The cult of Korczak reached a climax in the “studio home,” a museum-like collection of family possessions, decorative odds and ends that matched neither the mountain nor each other. Some examples: A 100-year-old organ, a harp, a grand piano, Japanese wall screens, a picture of the “consecration of Korczak’s tomb at Crazy Horse” (above a picture of Pope John Paul II: the Ziolkowskis are of Polish descent), a grandfather clock, an imitation chandelier, Norman Rockwell figurines, Korczak’s violin, Korczak’s palette, a Baroque mirror, a Chinese writing desk, a plaster-model of Korczak’s hand in a glass bowl, three immense paintings of Korczak and his wife Ruth (the dominant objects in the room), and sofas upon sofas, which I found especially odd. One of the most moving stories about Crazy Horse was his refusal, as he bled to death after being stabbed at Fort Robinson, to be laid down on a cot. He wanted to die on the floor, closest to the land “where my dead lay buried.”

At the entrance there’s a sculpture of two “fighting stallions,” and the inexplicable addition in 2012 of a 9/11 memorial made of a steel fragment from the towers. Plunder for tourism never ceases. “May we never forget what happened on that fateful day,” the dedication reads, stone deaf to the amnesia of the mountain. Walking everywhere on Korczak’s holy grounds, I missed Crazy Horse.

*

I looked for him in the emotions of visitors.

The guest-book was a long list of stunned, single-worded comments along the lines of “Awesome,” “Thank you!” “Great,” “Fantastic!!!” “Fabulous” “Unbelievable!” “Big!” and slightly longer reactions such as “An overwhelming endeavor,” “Thank you” and “Big change since 1950!” The mountain drew more than 1 million visitors in 1997 and expected to top that easily in 1998, because of the sculpture’s semi-centennial. A Bill Clinton desperate to escape Washington would visit a few months after I did, punctuating a four-day trip through poverty-ridden areas of the country, including Pine Ridge, with swings through Crazy Horse and Rushmore.

More than a few visitors would say how many times they had visited since 1948 and what progress had been made. They reveled in a mountain coming to life before their eyes, in the wrinkle-like blast-grooves on Crazy Horse’s face being polished away in a reverse-aging process. Some called it “A religious experience.”

Lois and Duane Schwichtenberger, both in their early 70s, visited the mountain for the fourth time in July 1998, spending almost a whole day there. They are originally from South Dakota, but had lived in Lakeland ever since Duane got out of the service some 50 years ago. Since I was on assignment for a paper based in Lakeland at the time of my own visit, I gave them a call from a payphone on the mountain, within sight of the sculpture. “We came with just about a suitcase apiece to decide if we were going to like it, and we’ve been here ever since,” Lois said from her home. She remembered her first visit there.

“They were just starting it, he didn’t even have the head anywhere near finished, he didn’t even have his eyes yet,” Lois said. “The second time we went he had just cleared his eyes, and what was said was, ‘Now Crazy Horse can see.’ One day Crazy Horse is going to put the presidents’ faces to shame, because this is so big and so moving. And to think that this goes out of the mountain, out of nothing.

The reaction of many visitors I spoke with on the mountain was similar. But it was always Korczak’s feat they liked to talk about. I was more curious about the relevance of Crazy Horse. Building a statue in his name is one thing. But what of living Native Americans and the ideals he wished for them? The question started a discussion between Helga and Gene Dickson, who were visiting from Texas as we stood on the observation deck, the temperature barely above 40.

“Where are you going to put them? Back in their original lands?” Gene asked, referring to Indians in general. “They had it all. All of this was theirs.”

“We’re an American people, and that’s what we should remain, all of us, no matter where we came from,” Helga said, her German accent still strong enough to denote her recent origin. In the distance, Crazy Horse had disappeared behind a thick gray mist.

“We cannot right that one,” Gene said. “Well, they no longer have to live on the reservation. They go to college. In fact, they get cheaper tuition than you or I do.”

“We cannot be held responsible for what happened 150 years ago.”

“Without the white man, where would they be today?” Gene said.

“Probably just roaming around and being happy,” his wife answered.

“Well,” Gene said, shivering in his t-shirt, “the Spanish brought them the first horses. They’d still be walking.”

I thought I was speaking with John Wayne, who in his 1971 Playboy interview had used nearly identical words: “what happened 100 years ago in our country can’t be blamed on us today,” he’d said. “But you can’t whine and bellyache ‘cause somebody else got a good break and you didn;t like these Indians are. We’ll all be on a reservation soon if the socialists keep subsidizing groups like them with our tax money.”

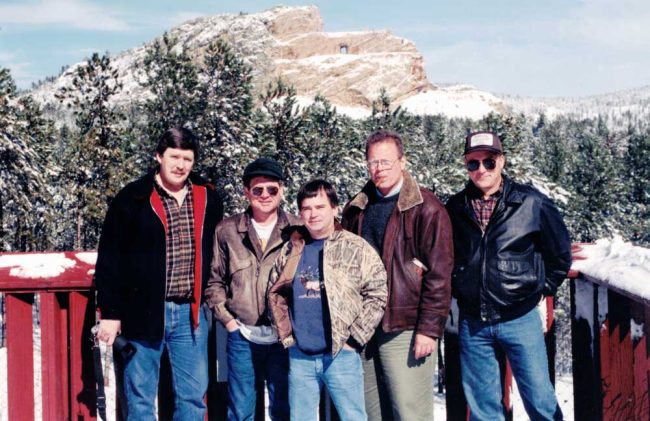

Two days later I spoke with five men who had gathered from across the country and from Brazil at Mount Rushmore and Crazy Horse Mountain for their 25th high school reunion.

“The past is always the past and it’s best to stay there,” said Henry Chidgey, chief executive of a rail line in Brazil. “But I think you can always acknowledge the greatness of people.”

“I look at this as a tribute, not as a memorial,” said his ex-classmate, Phil Owensby. “I don’t look at Mount Rushmore as a memorial. I look at it as a tribute.”

The ideals of the presidents on Mount Rushmore are still alive, and arguably still very strong despite their flaws. Projecting present biases on the past has its limits. But each of those four presidents had a hand in defeating the ideals Crazy Horse represented. Could the Crazy Horse monument be anything more than guilty payback, or, as Owensby had put it, “an apology from the white people”? Isn’t that how Korzack saw it in hsi 60 minute interview?

“By Carving Crazy Horse,” Korczak had said, “if I can give back to the Indian some of his pride and create the means to keep alive his culture and heritage, my life will have been worthwhile.” It sounds patronizing, like a more polite treatment of the Indian as noble savage: Korczak as the benevolent giver, carrying out his white man’s burden in a 20th century echo of Alexander Pope’s famously haughty “Lo, the poor Indian!”

I don’t mean that only Indians should build Indian monuments anymore than blacks should be the only ones to make movies about Malcolm X or Jews the only ones to design Holocaust memorials. Truth and beauty are matters of passion and commitment, not of race and heredity. But the passion and commitment of Crazy Horse Mountain seems misplaced, like a make-work project that justifies itself with a hip Indian theme. White and Indian cultures here are still on parallel lines, one using the other and revealing to the visitor more of its own power and glory than anything Indian. As the historian Robert Berkhofer noted of whites’ historical use of Indian images, “even today’s sympathetic artists chiefly understand Native Americans according to their own artistic needs and moral values rather than in terms of the outlook and desires of the people they profess to know and depict.”

The Crazy Horse monument was designed as only the beginning of a plan to turn the mountain into a 1,000-acre town with its own university, a “medical training center,” a sports facility and a major Indian museum, all of it devoted to Indian students, Indian artists, the Indian future. If that vision were to come true, the place may well prove to be a wondrous sort of cultural repatriation. But aside from a Native American museum and a summer program for college students who also work on the mountain, little of that vision is coming true.

It’s not for lack of money. In 2019, the year before Covid, the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation, the non-profit arm of the Ziolkowski’s organization (separate from Korczak’s Heritage, Inc., “a for-profit organization that runs the gift shop, the restaurant, the snack bar, and the bus to the sculpture,” according to a New Yorker report), had $20.5 million in revenue and $95 million in assets. What the organization was now calling a “campus” wasn’t short of the means of becoming one, though that, too, seemed like another bit of truthful hyperbole. In any case, the transformation was difficult to imagine because just as the spirit of Crazy Horse was missing from the mountain, so, too, were actual Indians.

At the time I visited only three Indians served on the 23-member Crazy Horse Mountain Foundation board, and they were outnumbered just by Ruth Ziolkowski, who chaired the board, and three of her children. Ruth died in 2014. The board is now chaired by Monique Ziolkowski, with two other Ziolkowski on the board. Few of the employees on the mountain were Indian. Ziolkowski when I spoke to her had said Indians tend to prefer family employment, or else she blames the better jobs on reservation casinos. Yet reservation unemployment was notoriously high — above 80 percent, according to Ike LeBeau, an employment training specialist I spoke with at the time, at a Sioux job agency in Rapid City.

Even the greeter at Crazy Horse Mountain, Jay Citron, was a New Yorker who had first read about Crazy Horse in The Weekly Reader when he was 5 years old, back in 1953, and who used to send his grocery-delivery money to Korczak. He has worked on the mountain for the last 10 years. But the Indians from down the hill, from around Rapid City, from those reservations that were looking to tap into the riches of the white tourism trade — they were not on the mountain.

*

Many Indians were in Ike LeBeau’s office even though his branch of the United Sioux Tribe of South Dakota Development Corporation was merely a door and a garage-size room in back of a strip mall. It was one of the first stops for Indians trying to make the transition from reservation life to white society — from one parallel universe to another. It’s a harrowing transition for many, exacerbated by a lack of education and the prevalence of racism.

“In this day and age people have found a lot of ways to be discreet about racism,” LeBeau said. “All my telling is not going to show it. You have to be one of us to feel and see the racism and discrimination. There’s no light way to explain that sort of thing. I’m not hostile about it, I’m more diplomatic because I understand more about it than I did 30 years ago, but a lot of reservation Indians don’t understand. It’s a culture shock for them. They have a chip on their shoulders. They’ll fight at the drop of a hat.”

LeBeau talked about change, and how even Crazy Horse Mountain was a good thing, even though he doubted that many whites visited the place to learn about Crazy Horse as a Native American role model rather than “to see how good a job they did with the sculpture.” And he talked of the hope he sees “all over, ever day.”

“Things are changing every day, no matter how slow. Even in my case, younger people come here and expect to see a white man sitting here, but they see me. They see hope. Older people come in and I get up and talk Lakota to them. Their eyes light up. They see hope.”

It was as if there was more of Crazy Horse in LeBeau’s isolated strip-mall office at the foot of the Black Hills than in all of Korczak’s thousand acres, though more than two decades later, just as the big sculpture had barely progressed, just before Covid unemployment was still 80 percent and more than half the Pine Ridge reservation population was living below the poverty line.

I hadn’t heard a word of Lakota on Crazy Horse Mountain. I wouldn’t have understood it, but I would have recognized its sound, the way it is easy to recognize the importance of Crazy Horse without knowing very much about him. But so much more than Crazy Horse was missing from the mountain that bears his name. Korzak’s glory was not the bridge between two unequal words his family pretends it is. Neither is a mountain where the only prominent Indian is made of stone.

*

In 1923, the Sioux filed suit in the Court of Claims, arguing that the government had seized their land without just compensation. The court dismissed the case in 1942. After Congress created the Indian Claims Commission in 1946, the Sioux resubmitted their claim. It was not until 1968 that the court ruled in the Sioux’s favor. They were owed just compensation: $17.5 million, a risible sum compared to the hundreds of millions or more in minerals and lumber that had been extracted from the land.

The federal government had argued that it should be credited the $43 million it had spent over the years to keep the Sioux from starving. The court disagreed. The government appealed to the Supreme Court. Twelve years later, the Supreme Court ruled 8-1 in favor of the Sioux, awarding an additional $105 million in interest–5 percent a year over 103 years, to be distributed to 60,000 people in the eight tribes.

The money with interest today has accrued to $2 billion, because the Sioux never touched it, and refuse to do so to this day. It’s not the money they want. They want the Black Hills returned. They have a case, and a stronger one than Palestinians’ Right of Return to Palestine: Israel is a settled, populated country. The Black Hills are not. Some Native Americans want Rushmore’s sculptures demolished. Some want the monument turned into a Holocaust Memorial, marking the Indian genocide.

Neither is about to happen: Rushmore and the exploitation of Crazy Horse are no less profitable than the gold that unleashed miners’ and Gen. Custer’s terrorism on the native tribes and the uranium that has powered nuclear plants and bombs since. The optical illusion of Thunderhead Mountain aside, they both are the faces of American supremacy and enterprise. They are the quintessential American monuments. Guilts may wax and wane, money owed may yet accrue more interest, but all eventually falls back in place. That 9/11 memorial on the Crazy Horse grounds wasn’t out of place. It was just an echo from Rushmore, and before that from John Wayne, whose face, like those of Woodrow Wilson, Susan B. Anthony, Elvis and Ronald Reagan were all petitioned for Rushmore.

“I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them,” John Wayne said in that notorious 1971 interview. “Our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.” We may have had a couple of decades when that sort of thinking was beyond the pale.

Then came George W. Bush’s 2002 visit to Mount Rushmore when his handlers positioned him just so his face would be photographed parallel to the four presidents, when he used one of the regions most sullied by American terrorism on the continent to exalt “the challenge of fighting and winning a war against terrorists,” and when he recast John Wayne’s words in language more accessible to visitor center enthusiasts: “I mean, after all, standing here at Mount Rushmore reminds us that a lot of folks came before us to make sure that we were free. A lot of pioneers came to this part of the world to make sure that enterprise could flourish. A lot of our predecessors faced hardship and overcame those hardships, because we’re Americans.”

I had mistaken Crazy Horse mountain for a memorial to Indians. It is more accurately understood as a triumph of that flourishing spirit of enterprise, as enduring today as it was in Deadwood’s glory days. The sculptures, all of them, reincarnate the business of America as business, to recall the words of Calvin Coolidge, the Black Hills’s original Little Boy.

![]()

JimBob says

What an excellent basis for multiple grade level lesson plans in Flagler County schools! Oh wait, I forgot who was presently Florida’s Governor! NEVER MIND!

He Who Fruit Loops says

Tim McGraw, conceived and lived for awhile in Jax. First hit song that launched his music career – Indian Outlaw.