| Skip introduction and take me straight to today's installment. An introduction to American Impressions: I was the luckiest reporter on the planet. I’d proposed to my editors at the Lakeland Ledger to send me across the country and write an essay on each of the 50 states. They went for it, handing me two credit cards, a camera and the vehicle of my choice--a Chevy Venture I rigged up with a library and a bed.  I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I spent 15 months alone on the road, logging 60,000 miles and four times as many words. The result anchored a weekly section throughout 1999, counting down to the millennium. What you’ll read here between Christmas and the New Year, when FlaglerLive traditionally pulls back on hammering you with hard news (and hammers you instead with pleas to support us), are the first few installments of that journey. While my reporting at the time forms the basis of the work, most of what you’ll read has not been published before. The rest has been extensively reworked and updated. I was not traveling to discover myself or get away from myself, I was not in search of America or of eternal truths. I’m not equipped for that sort of thing, being rather shallow, and I wasn’t going to pretend to understand a state or even a village from a passing week. Nor is this a travelog about food or fun places to visit or quirky people I met along the way. I was just a reporter, picking up stories here and there, choosing for each state one or two themes that struck me as telling about that part of the country, and hoping to build a mosaic of an America every inch a wonder and a puzzle of joys and sorrows to an immigrant hopelessly in love with his adopted country, despite and still. I hope you’ll enjoy the journey. --Pierre Tristam Previous installments:1. Introduction: The Day Before America | 2. Heartland | 3. The Road | 4. Alaska: The New Suburb | 5. Alaska Highway | 6. Montana: Backtracking Lewis and Clark | 7. Montana: Ghost of the Prairie | 8. North Dakota: A Life in Missiles | 9. South Dakota: Crazy |

“When I crossed into Montana, I felt I was almost home,” Ian Frazier writes in Great Plains. When I crossed, I felt I was home. I took U.S. 89 south to Babb and said “Babb” out loud three times, the time it took me to cross the no-horse town of three shuttered buildings. If Alaska’s vowels trail to the unknown, Babb’s consonants seemed to ricochet off the rock-ribbed slants of Glacier National Park to my right.

I was mouthing the name of a man who played a small part in opening that corner of the West. In the early 1900s Cyrus Babb, with a little help from Theodore Roosevelt, engineered the theft–called a diversion at the time–of the St. Mary River’s Canadian waters to the Milk River on the Montana side, irrigating an area twice the size of Maryland, enabling towns to grow, and doing in Montana what government exploiters, nowadays called the Bureau of Reclamation, the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service, have been doing to the West under different names since Lewis and Clark: remaking it in man’s image.

The Corps of Discovery, as the Lewis and Clark expedition was called, traveled the longest distance of its journey in what is now Montana, what was then undiscovered country for white colonists. My intention was to backtrack as much of the approximate trail as possible, juxtaposing what Lewis and Clark saw, or rather wrote about in their journals–a tantalizing difference–with what was there 200 years later. Babb’s diversion was an early hint.

Meriwether Lewis had been in the northeast corner of Montana, just east of the Rockies, toward the end of the journey when he “took leave of my worthy friend and companion Capt. Clark and the party that accompanyed him” so that he could explore the area of the Marias River. He wanted to see how far north the river went, and meet with Blackfeet Indians to deliver what he called his peace message — the same message he had been delivering to every Indian tribe encountered along the way: Thomas Jefferson is now your “Great White Father.” Behave as his “faithful red children.” Play nice with other tribes and we’ll protect you. The alternative was implied by the power of the Corps’ arsenal, until then the most powerful ever to make it that far west.

Most tribes welcomed white men, believing they would benefit from their protection and opportunities to trade. The expedition met resistance only twice in two years. The first incident occurred early on the way west, along the Missouri near the Teton River, in today’s South Dakota. A tribe of Sioux, the Plains’ and northern Rockies’ Alphas (or “true terrorists,” in historian Bernard DeVoto’s words), was dissatisfied with the amount of gifts they received. They tested the expedition’s strength.

A stand-off ensued over several days, the expedition’s Cuban Missile Crisis. Had a single shot or arrow been fired from either side a carnage would have followed, probably assuring both sides of mutual destruction and changing the course of American history. A Sioux who might have traced his cross-Bering ancestry back to Mikhail Gorbachev’s kin finally calmed everybody down, Lewis especially.

For all the brilliance he honed at Thomas Jefferson’s table as his secretary, Lewis was a moody, nationalistic hothead who today would most likely be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. There are months of silence in his part of the journals, a heartbreaking blackness that mirrored his soul on his travels. He was a manic depressive. He would die by suicide years after the expedition. He also was a supremacist–not in the unspeakable sense we give it today, so the terminology bears nuance: anachronisms aside, he would not burn crosses in anyone’s yard, but nor did he doubt who was civilized and who wasn’t, who were the savages and who weren’t, who was to submit, and who was to make them submit.

Not a single shot was fired during the Teton River standoff (“we were not Squaws, but warriers,” Capt. Clark told the Indians). But it was Indian indulgence and fear, not Lewis’s diplomacy or Clark’s rudeness, that ensured safe passage. The expedition’s reputation for resolve parted the West like the Red Sea for the rest of the way.

The second incident occurred on the expedition’s return, when Lewis met Blackfeet Indians while exploring the Marias, a few miles east of Babb. Lewis, who had only a few men with him, made a terrible tactical mistake, encouraging the Blackfeet to trade with enemy tribes. The Blackfeet suspected a trap. Tension rose. Indians stole some of the white men’s weapons. Shots were fired. Two Indians were killed. The expedition decamped and rode southeast for miles under moonlight before most of the Blackfeet realized they’d lost two men. Lewis and his men rode until two in the morning through a roll of empty prairie country that has barely changed since.

*

When the Corps of Discovery arrived at the Great Falls just outside what is today Montana’s second-largest city, a year after leaving St. Louis, Lewis described the five falls as “the grandest sight I ever beheld.” Their water “falling over the precipice beats with great fury” and crashes “into a perfect white foam which assumes a thousand forms in a moment sometimes flying up in jets of sparkling foam to the hight of fifteen or twenty feet.” (Here as elsewhere I am sticking to the original spelling in the journals.)

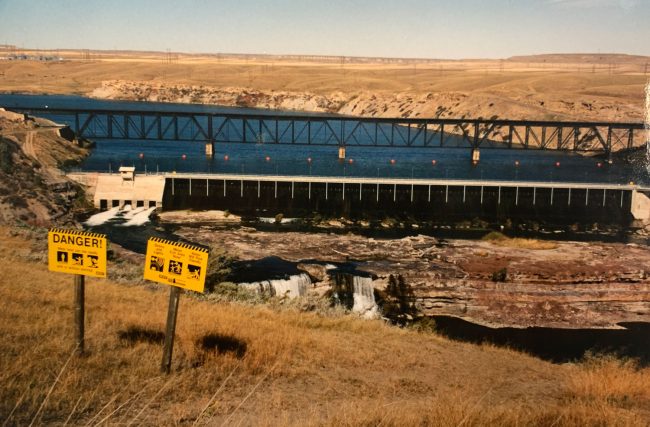

Lewis’ sparkling, present-tense descriptions are all that remain of the falls’ fury. Instead of crashing down five falls today, the Missouri butts up against five dams. One of them has submerged Coulter Falls. Lewis described Rainbow Falls as “one of the most beautiful objects of nature, its edges as regular and straight as if formed by art.” It is now a masterpiece disfigured by a discordant frame — a dam, a railroad bridge, a forest of high-voltage power lines behind it, signs warning the public against approaching the river-bed in front of it.

The dams are the legacy of Paris Gibson, who founded Great Falls in the 1880s with visions of harnessing the falls’ hydro power for the benefit of the world the way Cyrus Babb harnessed the St. Mary River. The plants that first generated electricity from the falls’ dams powered the copper mines of Idaho, which produced electric wiring that eventually gridded the globe. Lewis would have loved the dams. He’d have considered them an improvement on nature and a benefit to humankind.

*

The Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center sits on the banks of the Missouri, upriver from Rainbow Falls. Don’t confuse it with a visitor center. You can certainly buy the usual clutter that already fills your cupboards from previous expeditions elsewhere–the keychains and ball caps and coffee mugs that reduce American epics of landscape or history to jiggles and and shades and milliliters. But if visitor centers let the moronic tourist check off the been-there-done-that box with souvenirs, interpretive centers are wonders of roadside America. They’re among what the celebration of American heritage does best, bridging the distance between the academic and the everyday, between scholarship and relevance. In Great Falls, it was like stepping into a time machine inside a documentary universe, with the sights and sounds of the expedition all around, and with that script: those tightly handwritten lines of the journals that read like America’s Thousand and One Days, with Lewis and Clark for Sheherazades.

The center opened on July 4, 1998, after 10 years of grass-roots fund-raising in Great Falls. The city came up with $3 million to match a $3 million federal grant, and got its center largely through the efforts of Jane Webber, the center’s director when I met her. The center’s opening was roughly timed with the bi-centennial of the expedition a few years on. It was anticipating a rush of Lewis-and-clarkophiles.

“There’s no doubt about it that we’re on the crest of a wave,” Webber said happily. “We’ve got people coming from all over the world, not just this country. It’s just sort of this big machine now going down the track, and the more there is of it, the more people gobble it up.” The expedition produced enough grist for the botanist, the anthropologist, the historian, the geographer, the romanticist, the archeologist, the political scientist.

But like the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ run into America in 1992, the Lewis and Clark expedition re-emerged in a prison-house of interpretive quote-marks, of revisionism, of “yes, but”-qualifiers. At the centennial of the expedition in 1904, St. Louis hosted a world’s fair titled the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, drawing 20 million visitors to an event that also unveiled the hot dog, the ice cream cone and the song “Meet Me in St. Louis.” It was a celebration.

To Webber, the St. Louis example was history. “It’s not going to celebrate. It’s going to commemorate,” Webber said of the bicentennial. The interpretive center reflects the nuance. It conveys the sense that Lewis and Clark were not the first white men to see the West as much as the first white men to invade the West’s Indian country. They would never have survived the voyage without outpourings of the natives’ help along the way. Indian guidance turned the men of the Corps of Discovery into Indians to the extent that their survival demanded adaptation.

Clearly, there’s a dividing line between those who want to see Lewis and Clark as heroes, myths and all, and those who want to correct the course history gave them, and the role they gave themselves, as heroes.

“Anybody who’s even somewhat of a student of history of this country has to view the Lewis and Clark expedition as the significant event that changed the face of this nation from a few eclectic states east of the Mississippi river to a bi-coastal nation,” says Robert Weir Jr. He chaired the bicentennial committee of the National Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation as well as the University of Scranton, Pa., graduate education program when we spoke by phone.

“For that reason alone,” Weir said, “it’s very important historically. But from another perspective I also believe that this is America’s epic. This is the story of the kind of people that we are. It exemplifies our spirit, how we want to know what’s across over the hills, over the mountains and across the river. It helps to define what Americans are.”

Those who speak of the relevance of the expedition’s heroism for America contrast it with a presumed dearth of heroes on the American scene today. “We’re in search of heroes,” Joseph Musselman, a Lewis and Clark scholar who maintained the most complete site on the subject, told me. This was the autumn of Clinton-Lewinsky, keep in mind, but before social media’s cancel culture and nuking of privacy. “And goodness knows. Look around. We don’t have a lot of them right now. We subject all of our public servants to the kind of scrutiny that a hero can’t sustain, that we don’t give to a hero. Even our sports heroes are just analyzed to death, literally, and our movie heroes, they’re all tabloidized and scandalized and analyzed and we know too darn much about them. But here is a group of men about whom we can say, ‘My God, how did they do that?’”

To many Indians the answer is simple: They managed to do that because Indians helped them, and the expedition did not return the favor.

*

“We were their hosts and they were not very good guests,” Jeanne Eder, a historian and a Dakota Sioux, told me. After my stop in Great Falls I had driven south 220 miles to Dillon to meet Eder and see parts of the trail that proved to be fortunate turning points for the expedition.

It is at Camp Fortunate near Dillon that Sakagewea, the Indian interpreter who was traveling with the expedition, recognized her brother in a tribe of Indians that was not predisposed to be kind toward Lewis and Clark. Sakagewea had been kidnapped by a rival tribe when she was much younger. She married a French translator, the despicable Charboneau, who joined the expedition as it made its way west. The coincidental reunion was an astounding stroke of luck because it allowed the Americans to trade for horses and guidance with the Indians. Without either, the expedition could easily have perished, crossing the Great Divide. It was one of innumerable examples of Indian indulgence and know-how enabling what would be interpreted as American heroism.

Eder did not hesitate to say that her work on the National Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Council was all about redress. She was one of three Native Americans on the 25-member panel. “It’s time after 200 years that the native people got to tell their side of the story and to give a balance. That’s where your revisionism is going to come in,” she said.

“Are there not committee members who would like to see a celebration?” I ask Eder.

“I think there were,” she said, forming a wry smile.

“And you took care of them?”

“Yes, a couple of years ago, but now the committee has grown. We’ve gone through phases. We went through a phase where it was, you know, guns and glory, gung-ho celebration. We went through that phase pretty fast.”

Eder was raised in the Sioux culture on an Indian reservation. She’s not joking when, with her deceptively easy demeanor, she calls herself a warrior, and a descendant of warriors. Her war is lost now, and she doesn’t blame Lewis and Clark. “There would have been others,” she says. The movement west was inevitable. So she fights battles of containment, arguing for the sovereignty rights of Indian tribes inside their reservations or balancing the record of historical legacies such as Lewis and Clark’s. She was in her 20s when she first read the Lewis and Clark Journals — when she first came across those many passages where Lewis addresses Indians as “children,” and refers to Jefferson as their “Great White father.”

Eder knows the passages well. “I was very angry. It just reminds me of how for years history has been written to patronize Indians and remind people that the Great White father is here to take care of them.” She laughs at that, too.

Thomas Jefferson’s letter of instructions to Lewis had ordered that “In all your intercourse with the natives treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit.” But Jefferson left no doubt about the expedition’s aims — to open up the west to America’s trading interests — and its means: “To your own discretion therefore must be left the degree of danger you may risk, and the point at which you should decline, only saying we wish you to err on the side of your safety, and bring back your party safe, even if it be with less information.”

The expedition was armed to the teeth and always ready to use its weapons. It assumed that every tribe was hostile and uncivilized. It assumed, as only supremacists can, that every tribe would embrace white civilization as it encouraged every chief it proselytized to come to Washington, all expenses paid, meet Jefferson, and submit to the new regime. The message was basic: resistance is futile.

As the two incidents I described at the beginning of this installment illustrate, Lewis and Clark never really wisened up along the way. They felt wise enough. Their patronizing shows of force got bolder on the way back, as they met with tribes they had encountered two years earlier. One tribe that was still warring against another complained to Clark about its enemy, only to hear Clark wonder “how could they expect other nations to be at peace with them when they themselves would not listen to what their great father had told them.”

The more I read the journals or heard people like Eder speak of them, the more I thought of the expedition’s Indian relations as one of the nation’s earliest examples of its foreign policy — well-meaning, naïve, often disastrous in consequences. I began to see Lewis and Clark as the great white forefathers of The Quiet American, the Graham Greene novel of the 1960s about America’s lethal innocence in Vietnam. The weapons were different, the language was more quaint, the intentions were certainly different. The understanding of foreigners was not. It has always been incredibly simple-minded, stick-figured, it has always assumed the worst while still projecting more idealism than any other nation dares. The consequences have not often been something to celebrate.

I love the journals more than the men who wrote them. I admired the men’s courage: they’d inspire anyone even today. They were brilliant explorers, and as explorers go, they were among the most light-handed. Their predecessors raped and massacred natives for breakfast. Lewis and Clark drew flora and fauna, and turned down sex with natives more often than they accepted, though by the expedition’s halfway point Lewis, the Corps’ doctor, had treated every man for one STD or another. Any exploration disturbs its grounds, sometimes fatally, most of the time unwittingly. Lewis and Clark cannot be held responsible for 200 years of hindsight. They were more Enlightenment explorers than conquistadores, more well-armed nerds than vampires.

But if, as Oscar Wilde wrote, “the one duty we owe history is to rewrite it,” at least one of the duties we owe our understanding of the Corps of Discovery is to recognize that with all their unquestionable historic and literary beauty, the journals are also one of the single-most one-sided records of discovery in the annals of western exploration. The journals don’t need re-writing, nor do most of the stories surrounding Lewis and Clark. But story of the expedition has only gained from the Native American history of the trail finally being told in its own language, free of white fathers’ shepherding.

*

The expedition almost starved while crossing the Continental Divide on the Lolo Pass during the fall of 1805, by far the most difficult stretch of the expedition’s two-year journey. The ground was “covered with Snow,” two horses died, game was scarce, and one of the expedition’s sergeants called the Bitterroots “the most terrible mountains I ever beheld.” “We passed over emence hils and Some of the worst roade that ever horses passed, our horses frequently fell,” Clark wrote. Today, the Lolo Pass is the much-traveled, well-paved and painted U.S. Highway 12.

When the expedition made it across the mountains, it rode down to the Pacific Ocean on the “Mighty Columbia River,” not the longest river of North America but back then by far its most powerful, traveling almost twice as far as the Mississippi in half the distance and releasing energy equivalent to a Hiroshima bomb every half hour. The falls along the river frightened Clark with “the horrid appearance of this agitated gut Swelling, boiling and whorling in every direction.” No longer. The river is dammed in 16 places and managed down to the last drop. In A River Lost: the Life and Death of the Columbia, writer Blaine Harden called it a “managed pool.”

But some places are still enchanting. On Aug. 12, 1805, Lewis crossed the Continental Divide for the first time at the Lemhi Pass, on the southern end of today’s Montana boundary with Idaho along the Bitterroot Range. There, he saw the mountains of the west, and at that moment the myth of an easy Northwest Passage — which pioneers and presidents down to Jefferson were convinced existed — died. Lewis exulted anyway.

“At the distance of 4 miles further the road took us to the most distant fountain of the waters of the Mighty Missouri in surch of which we have spent so many toilsome days and wristless nights,” he wrote. “thus far I had accomplished one of those great objects on which my mind has been unalterably fixed for many years, judge then of the pleasure I felt in all[a]ying my thirst with this pure and ice-cold water which issues from the base of a low mountain or hill of a gentle ascent for 1/2 a mile. the mountains are high on either hand leave this gap at the head of this rivulet through which the road passes. here I halted a few minutes and rested myself.”

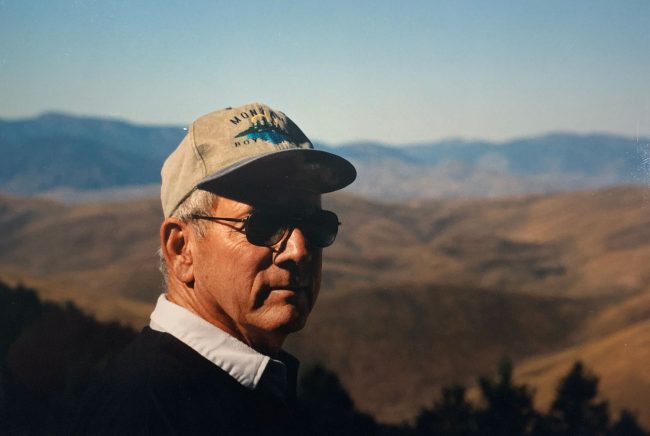

Chuck Cook was a 70-year-old retired history teacher when I met him, and the president of the Dillon-based Camp Fortunate Chapter of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. He took me to Lemhi Pass, where the spring still “issues from the base of a low mountain or hill of a gentle ascent,” and where I “allayed my thirst” just as Lewis had. “Go ahead,” Cook had to tell me, as if drinking from that cold trickle were some kind of communion with its more famous drinkers. Which of course it was. This was the place. This was the water source Lewis wrote about. This was where he rested, the way we were restring now. I was drunk on that water.

We reached the pass by climbing up a rutted and muddy one-lane road with Cook’s pick-up truck, driving two dozen miles without meeting another car. As we drove, Cook recited relevant parts of the journal from memory, the way Lewis and Clark lovers usually can, and stopped at Camp Fortunate. That, too, is now the location for a dam that has covered up the original site of the camp where Sakagewea was reunited with her brother.

But the submergence of history didn’t bother Cook anymore than it would have Lewis. Cook wasn’t much for lamenting what does not remain. He thrived on history and would rather not see its relics desecrated, but he didn’t see a dam or improving the road to Lemhi Pass as desecration so much as following in the footsteps of the expedition, with modern means. Cook, too, was a child of the Enlightenment’s idea of progress. “It was a Bureau of Land Reclamation project. It happened,” he said. And we moved on.

When we reach the top of the pass, Cook stood on the ridge between two rows of jack-leg fencing that delineate the Idaho-Montana border as well as the Continental Divide, and looked west just as Lewis would have. We saw a magpie of the kind Lewis first described (“they’d never seen one before,” Cook said as one flew by. “They’re kind of like a rat with wings”), then several black and white-tailed Clark’s jays.

The air was still, the sky cloudless, the mountains, not yet snow-capped on the Idaho side, visible to the horizon. They stretched like interlocking waves of colors and crests to a horizon that seemed to hug them from above, finite but infinite. I have always felt in the middle of mountains more awed and more moved than by any art in any museum, by any cathedral in any old European town, certainly by any palace or mansion anywhere. It isn’t faith that moves mountains. It’s mountains that restore faith. These mountains were their own beauty, but they were also a heartbreak, knowing as we now could what Lewis had no way to know: how far they stretched, how many days it would take the expedition to cross them, what hardship the Corps would encounter, how close they came to their demise, how more remarkable their triumph for making it through.

“It’s just a neat place, calm, peaceful, but I always think of what went through Lewis’ mind,” Cook says. “He must have thought, ‘Oh, Gosh. Gee.’”

We don’t know what Lewis thought of the endless expanse of mountains ahead because he didn’t say in the journals. But three months earlier he anticipated the difficulties. Mistaking Central Montana’s Little Rocky Mountains for the real thing, he “felt a secret pleasure in finding myself so near the head of the heretofore conceived boundless Missouri; but when I reflectd on the difficulties which this snowey barrier would most probably throw in my way to the Pacific, and the suffrings and hardships of myself and party in thim, it in some measure counterballanced the joy I had felt in the first moments in which I gazed on them; but as I have always held it a crime to anticipate evils I will believe it a good comfortable road untill I am compelled to believe differently.”

It would take the expedition more than a month to cross the range.

Before leaving the Lemhi Pass, Cook checked the guest book he kept for his Camp Fortunate chapter of the heritage foundation. Cleve and Marge Humphrey of Harvest, Ala., wrote, “Have followed the trail from St. Louis to this point. Following Ambrose’s Undaunted Courage.” And a woman whose name was not legible had written, “Sakagewea, my heroine, thank you!” The dot at the bottom of the exclamation mark was a heart.

*

Sacagewea, the Shoshone Indian woman who traveled with the expedition, tends to get most of the attention among the Corps’ supporting actors. She was centrally cast in the expedition’s mythology: She was young, nubile, pregnant, smart, pitiable–she was married to the wife-beating Charboneau, the trader and translator better suited for a waiter’s job in a miserable bistro somewhere dank, who couldn’t help but infuriate the travelers and drive Clark crazy for the shitty way he treated Sacagewea.

Clark wasn’t one to speak. He’d brought along York, the real hero of the expedition’s supporting cast. He alone, along with the expedition’s dog Seaman, is featured alongside Lewis and Clark in a bronze sculpture in Great Falls. He was a Black man who pulled his weight and then some, a marksman and ace hunter who helped stave off hunger for the expedition and was willing to die for it, a fascination to Indians as Lewis and Clark tuned his talent for entertainment into an early case of minstrelsy west of the Mississippi. York was such a fascination to some Indians that on one occasion it was York’s black skin, York as a phenomenon of nature, that bridged the way to bartering with Nez Perce Indians for horses.

He was also the first Black man freely to wield guns and to vote that far west, when the expedition put certain matters to a vote.

And he was Clark’s slave. Not an enslaved person, as more recent, more humanizing terminology has it, but a slave: Clark more than Lewis never let him forget it.

The men of the expedition had been promised land grants upon their return. Lewis also wanted them to get extra pay. He excluded York when he listed all those who’d made the expedition’s round trip. York thought he deserved his freedom as payment for his three-year service on the expedition. His wife, another enslaved person, belonged to another man in another state. He wanted to buy her freedom, too.

Clark refused, allowing him only to visit his wife in Louisville, Ky., and turning cruel against York when York insisted. “I am determined not to Sell him, to gratify him, and have derected him to return . . . to this place, this fall,” Clark wrote; “if any attempt is made by York to run off, or refuse to proform his duty as a Slave, I wish him Sent to New Orleans and sold, or hired out to Some Sevare Master untill he thinks better of Such Conduct. I do not wish him to know my determination if he conducts himself well.”

Clark brutalized him at will for being “sulky” and sublet him to a different master known for his violence. Lewis did not intercede. Only about a decade or so later, Clark in a letter suggests he’d finally given York his freedom, but that York had squandered it, fell with cholera and died. It’s Clark’s account. Whether it’s true or not is debatable. But while Clark raised Sacagewea’s child as his own, nothing in the record indicates that he ever treated York either with the dignity or gratefulness owed one of the great American heroes of the West.

*

Descriptions of Eden-like abundance of wildlife on the Plains are just as abundant in the journals. “This scenery already pleasing and beautiful was still farther hightened by immence herds of Buffaloe, deer Elk and Antelopes which we saw in every direction feeding on the hills and plains,” Lewis writes early in the expedition. “I do not think I exagerate when I estimate the number of Buffaloe which could be compre[hend]ed at one view to amount to 3000.”

The abundance wouldn’t let up until the Rocky Mountains. Bears seemed to be everywhere, including white bears. Pastures were “boundless,” streams and rivers as clear as they were rich in fish. Every day was a Discovery Channel nature show. Today, wildlife has been tamed to the point of invisibility on the Montana plains. Chuck Cook showed me a few elk, but they were fenced in on a farm, raised for their antlers, which are sold to Japan as an aphrodisiac. We also saw a coyote parallel the truck for a mile then disappear behind a bluff, but no wolves. I’d heard a scary, unidentified growl the first night in my van in eastern Montana. That was it for wildlife in five days across Montana.

But backtracking Lewis and Clark is as revealing for what’s along the trail today as what’s not. Lewis and Clark’s 600 campsites — only a few of which have been authenticated — cut a 19th century interstate of conquest, trade and settlements. In a few generations the plains have been emptied of wildlife, Indians have been segregated, rivers diverted, dammed or submerged, and untold features in the land altered to make way for the mound-like beds of roads and actual interstates. It’s the price of life as we choose to live it.

The plains are also exacting a price. Aside from the western mountains that are becoming a salon community of Hollywood exile, Montana is emptying out. Old people are dying, young people are leaving, towns are disappearing. The rain never really followed the plough, and the plough is too expensive to maintain west of the 100th meridian. Clark had found the Montana country “roleing & of a very rich stickey soil producing but little vegetation of any kind except the prickley pear, but little grass & that verry low.” That much hasn’t changed. A few people joke about returning the plains to the buffalo. The joke is more muted when the suggestion concerns Indians.

Driving through the heart of Montana, north from Billings to Malta on two-lane U.S. 87 and 191 (toward the Little Rocky Mountains Lewis mistook for the big ones), the empty road is dotted with a few isolated farmsteads in ruins, a few towns propped up by Social Security and the local gas station, and the most unsettling feature of all, because it’s so frequent — white crosses by the side of the road. I counted 17 between Billings and Malta, a stretch of 200 miles of barely-traveled road, and probably missed many.

Road fatalities, yes. But not just.

U.S. 191 was part of the Nez Perce trail, where 239 of Chief Joseph’s band of men, women and children died as they were being pursued by Gen. O.O. Howard (who lost 266 men in the campaign). The Nez Perce Indians had saved the Lewis and Clark expedition as it emerged in tatters on the western side of the Rocky Mountains. Seventy years later, they were themselves reduced to tatters as gold prospectors chased the tribe out of the Idaho lands it had occupied for centuries. The white crosses by both sides of the road could just as well have marked the site of fallen Indians and Americans on the trail.

*

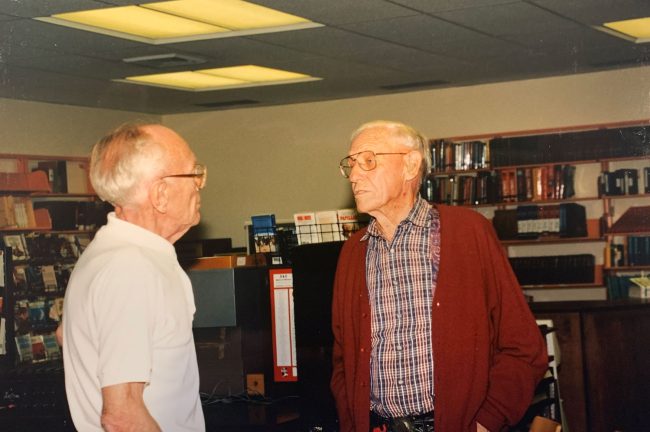

I turned east on U.S. 2, driving from Malta to Glasgow along a tributary of the Missouri. It was 7:20 p.m. when I entered a diner on Glasgow’s Main Street. A stack of newsletters about town news, dated from the same day, sat on the counter. The front page announced a lecture and slide show entitled, “Eastern Montana: Paradise or Purgatory?” to be delivered at the local high school library by a Don Baker, a “Montana historian.” The public was welcome.

The library was full ⎯ 93 people ⎯ as Baker showed his slides and commented in what became a predictable pattern: First the black and white or yellowing slides of bustling towns, large, smiling group shots outside school houses or businesses, main streets of the 1920s and 1930s dusty and confusing with action. Then, the color slides of the same towns or school buildings or businesses, but shuttered, dead, in ruins. It reminded me of pictures of coal mining country in Southern West Virginia, where I lived for several years, where every third hollow it seemed in the 1940s and 50s was its own bustling community of coal-grimed workers, women and children, their white teeth gleaming in black and white group shots. Now the same places are hollowed out, as unsmiling and decayed as a mouthful of lost teeth. So it was in the Montana Don Baker was sliding.

Melstone: “What was one time a community of 1,200 is a community of 200 today,” held together by one last oil field at the north end of town.

Emory: “It was a town that didn’t last very long. The soil here is very rocky, very shallow, and it’s windswept. This is all that remains, a school that became a community hall.”

Ismey: “This became a town of about 1,200 people. It had two of everything. Two banks, two mercantiles. The editor of Ismey’s newspaper, then called the Yellowstone Evening Journal, stated that on Saturday night the streets of Ismey were busier than Chicago’s. It became quite a town.” Today, Ismey is a town of 21, its cemetery outnumbering the living by more than 10-to-1.

And on Baker went. Mona. Plevna. Mildred. Carlyle.

At the end of the lecture Jack Schye, 85, a native of Ismey, chatted with Baker for a while, sharing the sort of memories Baker has collected in his book, Ghost Towns of the Montana Prairie.

Over coffee later Baker, who was 72, told me he was originally from St. Paul, Minn. When 3M transferred him to Montana in 1950, he never returned. But the four kids he raised all left the state. “Montana has been an extractive state from day one, whether it’s minerals or agriculture. But the biggest extraction has been kids. We educate them, and they move out. That’s my four kids.”

Yet 75 years ago there’d been a farm on every section. What had led to the emptying, and emptiness, of today? The opening of the west had been a great seduction to people. But the 328-acre allotment under the Homestead Act of 1862 had been all wrong for the Montana Plains, where it rains or snows half as much as it does in the eastern Dakotas, for instance. Out here, a farm couldn’t be viable with less than 2,500 acres. People tried hard, then failed in droves with economic downturns like the Depression.

“They came, they saw, but they didn’t conquer,” Baker said. “Nature is taking it back. It was oversold. There were people who came here thinking they could grow bananas. You have to be smart to survive in Montana. You have to be smart and ambitious and resourceful.”

Like Lewis and Clark, which not everybody can be, or needs to be, as the superrich white grandfathers turning western Montana into a version of Newport, R.I.’s Mansion Alley remind us with their faux ranches, genetically altered bison and semi-retired dancers with wolves.

*

William Least-Heat Moon writes admiringly of the Lewis and Clark journals in his Blue Highways. But he asks a misplaced question: “In our time, who of the many astronauts has written anything to compare in significance or force of language?” It’s true. None has. But none has needed to, when Apollo’s one iconic portrait of blue Earth in deep space is as moving as anything in the journals, or Walter Cronkite’s live broadcasts of Apollo 11’s landing are still as powerful to watch today as they were then.

The journals were the product of their place and time. Their authors knew they were documenting a continent. It was their job. They just couldn’t be sure their words would ever be read. They didn’t have the luxury of couriers or pony expresses, or risk sending back the volumes with a smaller party that could be ambushed or lost. On a few occasions the journals were almost lost, as when a boat sank. They’d been safeguarded in an impermeable bag.

But Lewis and Clark never set out to write a literary classic, or to write it in a language as purely American–not English–as we’d had until then. Long before Emerson asked American writers to turn their back on European masters and to be their own, Lewis and Clark had done so in the journals. Their artistry was that much purer, that much more originally American, for being entirely un-self-conscious about it. They unknowingly created a classic of the road, America’s first, preserving in immersive detail the very America their expedition helped vanish.

Stephen Ambrose in Undaunted Courage compares Lewis’s prose to “the stream of consciousness of James Joyce or William Faulkner, or the run-on style of Gertrude Stein—only better, because he was not making anything up, but describing what he saw, heard, said, and did.” It’s not an exaggeration. There is a sense of genesis to the prose, as if all of America’s language would flow from it. We shouldn’t be surprised. Lewis had learned his craft from the author of the Declaration of Independence. The journals are one of its fulfillments, if not yet fully achieved, as Jeanne Eder would caution.

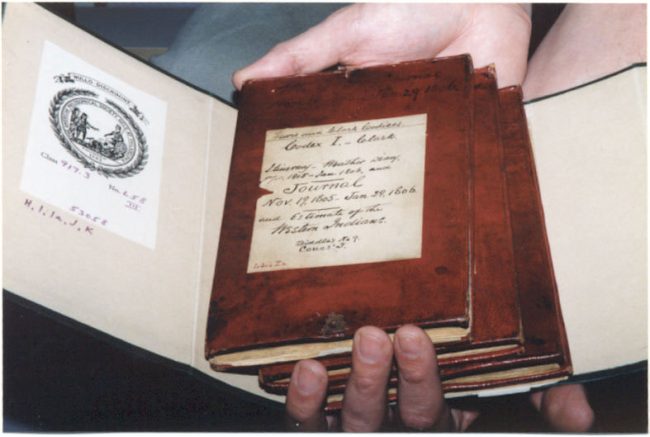

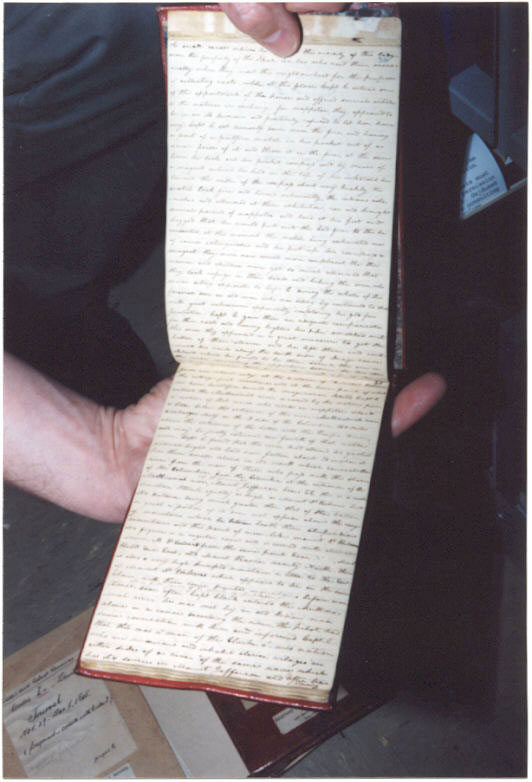

Three months after backtracking Lewis and Clark in Montana, Robert Weir Jr., the bicentennial committee chairman of the National Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, took me to the archives of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. We went down into a basement, down a sets of narrow stairs, through what seemed like door after door, through narrow openings between shelves stacked with books and boxed up documents, until we reached a spot where Weir crouched, pulled out one of two black boxes, opened it, and revealed inside a set of burgundy notebooks that flap open from the top.

There they were. The actual journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, their handwriting in ink and on paper that had crossed those Montana trails and mountains and rivers all the way to the Pacific and back. I was back at the headwaters of the Missouri in that Philadelphia basement, drunk with that icy water, drunk on that handwriting, drunk on Montana.

![]()

Pogo says

@Mr. Tristam

As you know, I’m fond of video clips in my comments. Some years back, I was looking for one with a particular line of dialog from the movie Little Big Man. You had already been there:

Amen.

It seems AI5 and AI6 are being received rather somberly, as well, IMHO, they ought.

Thank you.

Zhang Yong says

I have been Montana once ; happy place, Good Fortune

JEK says

Thank you

James says

“… The library was full ⎯ 93 people ⎯ as Baker showed his slides and commented in what became a predictable pattern: …”

By the way, I’m curious…. with all those places he researched and documented, did he ever mention any towns where the newly elected major proposed to raised his pay 150%? Even as a joke in passing?

‘… “They came, they saw, but they didn’t conquer,” Baker said. “Nature is taking it back. It was oversold. …’

Does this sound familiar?

Denali says

Manifest Destiny. The White American’s path to the destruction of all that is different. It’s past lies in slavery, degradation of other humans and the environment and then total dominance. While in 1803 the term was not in use, this is where it was conceived. White man’s dominance of the sub-human Native Americans was a simple continuation of the enslavement of the Black Man. The White Man in this country has always demanded that those different than him bend their knee and seek his benevolence. The Chinese who built the railroads, the Japanese businessmen, doctors and scientists, the Jewish bankers and lawyers, the Native American’s who led a simple life and did not believe in land ownership – the White Man through his envisioning of himself as the master of the world has beaten, whipped, kicked and demeaned everyone and everything that did not fit with his plans of domination. He has reshaped the earth to try and grow crops in a desert, to generate electricity for his homes and in the meantime starved populations down stream of water for basic needs, killed the buffalo to graze cattle and suffocated the salmon in their river beds.

Manifest Destiny. It is still with us. I saw it today at a local store where a band of marauding jerks chose to belittle an older Asian couple for nothing more than their eyes and skin tone. It was over in less than a minute but the message was clear; ‘We are the dominate group and you will yield to us’. Nothing less than the image portrayed by Lewis and Clark.

As I typed the word ‘image’ all that came to mind was “Imagine” – if you can . . .