The jury will have many more opinions than facts to digest when it begins deliberating Tuesday morning over whether to recommend death for David Snelgrove, or let him live out his days in prison, as he has for the past 20 years. If the jury is to recommend death, it will have to do so with a unanimity nowhere evident in six days of trial, when every point in contention was dueled over like in a tug of war between the prosecution and the defense that by its very nature could create reasonable doubt about either side’s case.

Unanimity is not necessary for a recommendation of life in prison. It would take a mere one juror to lean that way to seal that decision for Snelgrove, whose voice the jury never heard once as he sat at the defense table, slightly grizzled and paunched by age, a look oddly benign, sometimes vacant, occasionally weepy over memories of the crime, all of it contrasting with the brutish, calculating killer the prosecution wants the jury to see in him.

For two and a half days the jury heard competing doctors and psychologists duel over Snelgrove’s brain, his intelligence or lack of it, his troubled youth, his terrible years in schools before he dropped out, his crack addiction, and whether any of it could explain why he went from burglar to murderer one night in June 2000 in Palm Coast’s B Section.

The defense’s experts said of course it did: Snelgrove was borderline intellectually disabled, he had a smaller brain than usual, his mother was a drunk even when she was pregnant with him, he’d fallen on his head when he was small, he was on drugs. He’d snapped.

The prosecution’s experts said of course it didn’t: Snelgrove wasn’t the brightest man but he was still holding jobs, he knew what he was doing, his brain was normal, the defense’s experts didn’t know what they were talking about, they were making things up, making excuses for what he did on June 23, 2000.

That was the night when, hours after he’d twice borrowed $50 on two separate occasions from Glyn Fowler–because that’s the kind of man Fowler was: giving the shirt off his back to those in need wasn’t just an expression to him or to his wife–Snelgrove broke into the Fowlers’ house, likely startling the Fowlers awake, found himself confronted by Glyn, who was 84, then murdered him and his wife Vivian, who was 79. Both were frail. They were the parents of a son and a daughter.

Snelgrove didn’t just murder them. He bludgeoned, stabbed and strangled them, turning their bedroom sanctuary into a seventh circle of hell. Assistant State Attorney Jennifer Dunton flashed pictures of that bloody scene on oversize television screens all over the courtroom this afternoon during her 70-minute closing arguments: Glyn and Vivian, lifeless on the floor of their room, their nearly two centuries of life between them mutilated out of them in seconds by a 28-year-old man looking for his next fix.

The pictures were gratuitous, as had been the two previous times the prosecution–Dunton was joined by Assistant State Attorney Mark Johnson–had shown either video or pictures of the crime scene, each time sending the Fowlers’ daughter, who sat in the first row of the gallery throughout, into convulsions and sobs clearly audible to the jury.

That was the prosecution’s intent: to shock the jury, to elicit emotion from the Fowlers’ daughter, to do everything it could to lead to Dunton’s conclusion this afternoon: she asked the jury of seven men and seven women (including the two alternates) to recommend death for Snelgrove, because what the prosecution described as the heinousness and brutality of the murders, and as Snelgrove’s intent to murder his former benefactors, required it.

But the prosecution had an advantage that would be termed unfair in any other criminal-trial circumstance, when trying an individual for the same charge more than once is unconstitutional. The prosecution knew what the jury was not told, and would not be told at any point during the trial: that with all that same evidence, two previous juries could not agree unanimously to recommend death for Snelgrove. The first jury split 7-5 for death, the second jury 8-4. In any other state but Florida and perhaps one or two others, that kind of split would have meant life in prison without parole for Snelgrove, not death.

But Florida allowed the death penalty for defendants even if the recommendation was not unanimous–even though for any other crime, including stealing a pack of chicklets from a drug store, a jury had to be unanimous to find the defendant guilty. Florida excused the difference by splitting the penalty phase from the conviction phase of the trial. Snelgrove had in fact been found guilty of the murders by a unanimous jury (and of robbery, and of burglary).

But in the penalty phase, the juries couldn’t agree unanimously, because the defense had made strong arguments putting forth “mitigators,” elements behind the crime that mitigate its severity and, at least for some jurors, outweigh its “aggravators.” A jury must find “aggravators” to recommend death. It must find “mitigators” to go for life in prison. Either way, the defendant will be punished. The question is how.

Snelgrove was never put to death because the law, like the medical science about his mental and emotional abilities, has changed: the nation’s highest court in 2016 found Florida’s death penalty recommendation scheme unconstitutional. A jury had to be unanimous to recommend death. The following year the state supreme court ordered a new penalty-phase trial for Snelgrove.

And so since last week and for the past six days in court, the now 47-year-old defendant had to face his third such penalty-phase trial–a third “bite at the apple” for the prosecution, as Michael Nielsen, Snelgrove’s defense attorney, put it to the judge, out of hearing of the jury: the jury wasn’t allowed to hear that, either.

The defense relied on its expert witness, doctors and psychologists, and the recollections of Snelgrove’s aunt (who was a neighbor of the Fowlers’) and his older brother by nine years, to paint a picture of a youth, adolescence and young adulthood of Snelgrove as a man ruled by a dissolute mother and a violent, uncaring father, parents who let him fall out of a shopping cart and crush his skull one day when he was a toddler, parents who didn’t give a fig about his school work or knew how to parent, and whose premature deaths a month apart, two years before the murders, had him end up living with his aunt in Palm Coast. He held menial jobs, cooked for his aunt, was a kind man, according to her (he, too, would apparently give the shirt off his back, though he didn’t have as much to give).

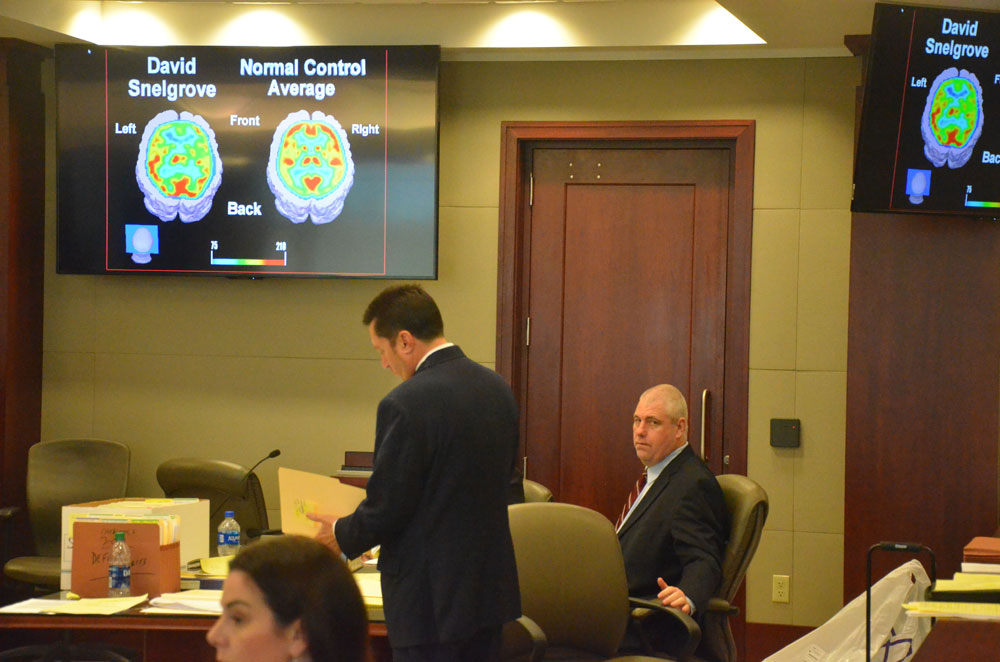

The clinical and forensic pictures, flashed on the same oversized screens as were the pictures of the Fowlers, were more stark: pictures of brain scans intended to show that Snelgrove was not a normally functioning human being with a normal-sized brain, but someone who showed signs of trauma, of fetal alcohol syndrome–meaning the fetus was damaged or its normal development inhibited from the mother’s drinking during pregnancy–and of microcephaly, the condition where the brain is smaller than normal.

One doctor in particular, Joseph Wu, formerly of the University of California at Irvine, made the case for Snelgrove’s abnormalities, constantly referring to Snelgrove’s color-coded PET scan as proof, leading to what he called “a significant impairment in his ability to conform his behavior within the requirements of law.”

The problem is that Wu doesn’t come without baggage. He’s a controversial physician whose work has drawn attention. Referring to the UC Irvine Brain Imaging Center he led until two years ago, the Voice of OC in Orange County reported in 2014 that Wu and the center “earned a national reputation for dubious use of the technology for forensic diagnoses in court cases, which records show can bring in more than $20,000 per case.” Wu’s focus has been Florida’s death row.

“For years,” the news site reported, Wu “has been flying to Florida to provide mitigating testimony, either at trials or at post-conviction hearings on death sentences. This has earned him a questionable reputation from coast to coast. A Los Angeles federal judge in a 1997 cop-killing case called him ‘a hired gun anxious to make the PET scan the instrument of truth.’

Larry Holder, a courtesy professor at the University of Florida’s Department of Radiology, has been calling Wu the professional equivalent of various derogatory names for the prosecution for years (he calls his work “hokum” in the Voice of OC article). The jury likely knows none of this backstory and wasn’t about to be told. But Holder was the prosecution’s chief rebuttal witness today in Snelgrove’s case, all but calling Wu a quack–a term Nielsen actually used to describe the way Holder was characterizing his witness.

Holder called Snelgrove’s PET scan and MRI “normal.” He called his intelligence less than average, but not in the disability range. He called his act against the Fowlers knowing, contradicting Wu, who had concluded that Snelgrove had “a significant impairment in his ability to conform his behavior within the requirements of law,” and described him as “someone who had extreme mental disturbance.”

But neither Wu nor Holder had ever met Snelgrove. Neither had had any kind of conversation or much familiarity with the case beyond Snelgrove’s imaging history. They were both hired guns, and both sides tried to make that point. Wu happens to make about $300,000 a year from his testimonies, Holder much less.

Which left it up to the two sides’ attorneys to make their case to the jury this afternoon in closing arguments, each side trying to discredit the other sides’ expert witnesses, the prosecution making Snelgrove out to be an unimaginably cruel killer, the defense making him out to be an imbecile who snapped.

Capital murder is pre-meditated murder. And though the defense could not refer to the procedural history of Snelgrove’s case, it had this going for it: the killings were heinous, a fact the defense is not disputing, but the killings were not pre-meditated. The burglary was. But beyond that, and thanks to the evidence–those pictures, the video–the prosecution flashed, it was just as clear that Snelgrove had not thought through his burglary. He had not thought much. He’d gone there barefooot. He’d cut himself breaking in. He’d walked on glass. He’d left his bloody footprints all over the place.

“It was the clumsiest most spastic murder in the history of crime,” Nielsen, the defense attorney, told the jury. “There’s no pre-planning to this, there’s no thought to it.”

For the jury to reach a recommendation of death, it must find unanimously for the six aggravators the prosecution presented, beyond a reasonable doubt. No such high bar exist for the defense: a single juror may have doubts, a single juror may find the defense’s mitigators to outweigh the prosecution’s aggravators. That will be enough to send the recommendation to life in prison without parole–that is, to keep Snelgrove at his current status.

The jury will begin deliberating a little after hearing Circuit Judge Kathryn Weston’s instructions at 9 a.m. Tuesday, in Courtroom 301 at the Flagler County courthouse. Weston told the jurors to bring a change of clothes Tuesday: if for whatever reason the jury is unable to reach a verdict after a day’s worth of deliberations, it will have to continue deliberating on Wednesday. But it will also, by law, have to be sequestered Tuesday night, in a hotel, without television, without phones, without contact with anyone else. That’s why deliberations didn’t begin late Monday afternoon.

And when it’s over, it still won’t be over, if he gets a death recommendation and the judge imposes death: Snelgrove could appeal the sentence, stretching the case into its third decade of procedural bumbles and wobbles.

Leave a Reply