By Susan L. Cutter

When the head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s urban search and rescue team resigned after the deadly July 4, 2025, Texas floods, he told colleagues he was frustrated with bureaucratic hurdles that had delayed the team’s response to the disaster, acccording to media reports. The move highlighted an ongoing challenge at FEMA.

Ever since the agency lost its independent status and became part of the Department of Homeland Security in the early 2000s, it has faced complaints about delays caused by layers of bureaucracy and red tape, leaders at the top with little experience in emergency response, and whiplash policy changes.

Now, the Trump administration is cutting jobs at FEMA and talking about dismantling the agency, which would push more responsibility for disaster response to the states.

Yet, federal emergency management is crucial in America.

I run the Hazards Vulnerability & Resilience Institute at the University of South Carolina and for years have worked with states and communities facing hazards and disasters. To better understand FEMA’s value, let’s take a look back at how the nation responded to disasters before the agency existed, and what history reveals about when FEMA was most effective.

Disaster response without the US government

Before 1950, disaster relief and response were not considered a federal responsibility. When a hurricane, flood or tornado hit, community members and humanitarian groups, such as the American Red Cross or Salvation Army, brought in food, shelter and medical aid and solicited charitable donations to help people rebuild.

State and local governments had primary responsibility for disaster response. But mostly people relied on family, neighbors and charity.

Archival Photography by Steve Nicklas, NOS, NGS.

Federal aid was approved on a case-by-case basis. War Department guidelines in 1917 stated that aid would be allowed only if a senior military officer certified that responding to the disaster would exceed local and state resources.

Then the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and the 1930s Dust Bowl gave new meaning to the concept of disaster in America.

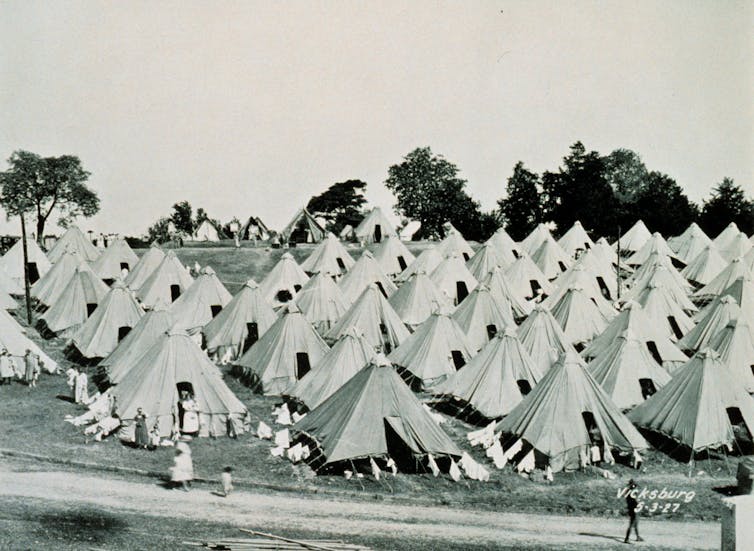

In 1927, the Mississippi River broke through its levees, submerging more than 1 million acres of land across seven states. An estimated 700,000 people were displaced from their homes and workplaces.

Historic NWS Collection/NOAA via Wikimedia Commons

Herbert Hoover, then U.S. commerce secretary, was given full authority to create, coordinate and carry out the federal relief effort. The Red Cross set up camps using tents provided by the War Department. Coast Guard and Navy boats rescued people stranded by flooding. But the response drew criticism for the lack of direct federal money to help flood survivors and the treatment of Black sharecroppers and laborers.

A few years later, the droughts of the Dust Bowl era began destroying crops in the Great Plains, causing widespread damage.

Federal disaster aid begins to take shape

After the flood, the federal government began to formalize its role in disaster management.

Flood control projects became a federal responsibility with the passage of the Flood Control Act of 1928. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal provided emergency relief to farmers in the Great Plains and set up the Soil Conservation Service to help them reduce the effects of future droughts. These were among the first disaster mitigation policies at the federal level.

AP Photo

There was little coordination among agencies, however. Various aspects of disaster relief and recovery were handled by the departments of Defense, Agriculture, and Housing and Urban Development and the Small Business Administration. Each had its own rules and requirements.

In 1950, Congress passed the Federal Disaster Relief Act, establishing the first permanent authority for federal disaster relief.

The act gave the president the responsibility to determine how aid would be distributed and which agencies would be involved. The legislation also broadened the federal mission to include disaster preparedness and mitigation and formalized the process for issuing presidential disaster declarations.

The creation of FEMA

By the 1970s, large-scale disasters such as hurricanes Betsy (1965) and Camille (1969), and the fragmented disaster response, led the National Governors Association to call for a single comprehensive emergency management agency. Its report provided the blueprint for President Jimmy Carter’s 1979 executive order that established the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA.

The new agency became the home for emergency management within the executive branch. It was intentionally designed as an independent federal administrative agency that could work across federal agencies to support state and local governments in times of crisis.

Andrea Booher/FEMA News Photo

FEMA wasn’t created to lead the disaster response. Instead it helps state and local officials by mobilizing federal resources, such as search and rescue, debris removal and funding when a disaster overwhelms the state’s capacity. FEMA could do this quickly because of established federal contracts and its ability to move equipment and responders into the region before a disaster hits.

When things began to fall apart

However, FEMA’s ability to act fast changed after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The agency was restructured as a unit in the newly formed Department of Homeland Security. But the Department of Homeland Security’s focus was on terrorism and law enforcement, not natural disasters.

The loss of autonomy and direct reporting to Congress, unfunded mandates outside the scope of the 1988 Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, and major increases in the number of large and complex disasters stretched FEMA’s capabilities.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, FEMA’s response drew widespread criticism. It was slow to deploy people and supplies and lacked enough experienced responders who knew what to do. Decision-makers were not familiar with new national response plans. Further breakdowns in communications and a lack of coordination among agencies led Congress to declare the Hurricane Katrina response a failure of initiative and agility.

AP Photo/Andrea Booher

FEMA’s reputation improved after the government brought in more experienced leadership and committed to preparedness planning and better response capabilities.

However, the first Trump administration, from 2017 to 2021, reversed those gains. Three different heads of FEMA in four years led to understaffing and conflicting directions.

As Trump took office for the second time in 2025, he and his administration talked about dismantling FEMA and pushing more disaster management to states. Job cuts and resignations at FEMA reduced the number of employees with training and experience vital in disasters. Political appointees to senior roles in the agency and in the Department of Homeland Security lacked emergency management training and experience.

A new policy that all purchases over US$100,000 be personally approved by Homeland Secretary Kristi Noem led to more resignations. For disaster response, a delay in waiting for a signature to work its way up the chain can cost lives.

What now?

Dismantling FEMA and leaving little or no federal coordination of disaster response puts states in a difficult position.

States must balance their budgets every year, and increasingly “rainy day” funds are insufficient to cover unexpected large disasters. As the federal government shifts other financial responsibilities to states, funds will diminish further.

A single disaster can cause hundreds of millions of dollars in damage and require widespread disaster response and then relief efforts. Since 1980, the cumulative cost of weather-related disasters has exceeded $2.9 trillion. With a warming atmosphere producing more intense storms, increasing human and economic harm are likely.

Members of Congress have proposed making FEMA an independent, Cabinet-level agency again. I see some distinct advantages in doing so:

- Fewer management layers would enable faster deployment of federal supplies and personnel to assist disaster response.

- A streamlined, more nimble agency could cut red tape for disaster survivors needing assistance, meaning delivering relief funding faster and more equitably.

- If an independent FEMA had responsibility for recovery beyond its current 180-day reimbursement limits, that could improve long-term recovery efforts, especially if Congress provided permanent funding streams and consistent rules and regulations.

The Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle FEMA are shortsighted in my view. Instead, I believe the best move is to restore FEMA as an independent executive agency as it was originally envisioned.

![]()

Susan L. Cutter is Distinguished Professor of Geography and Director of the Hazards Vulnerability & Resilience Institute at the University of South Carolina.

Mike C says

COVID-19 Funeral Assistance:

The DHS OIG found that FEMA reimbursed ineligible expenses, including unallowable costs, due to a lack of adequate guidance and training for caseworkers.

Emergency Food and Shelter Program:

An audit revealed that FEMA failed to reallocate unused grant funds, leaving $45.2 million unspent from 2017 to 2020, instead of reallocating them to other recipients who could use the funds.

Individuals and Households Program (IHP):

The OIG identified over $3 billion in improper payments between 2003 and 2020, stemming from a lack of verification and reliance on self-certifications for applicants claiming no homeowners insurance.

Debris Removal:

In Monroe County, Florida, FEMA reimbursed local entities for questionable costs and contracts that may not have met federal procurement requirements due to inadequate review processes and training.

Key Factors Contributing to Waste and Abuse

Control Weaknesses:

A lack of effective mechanisms and internal control deficiencies make programs more vulnerable to fraud and mismanagement.

Inadequate Training and Guidance:

FEMA has been found to lack sufficient training and guidance for caseworkers and local entities, leading to improper decisions and reimbursements.

Reliance on Self-Certification:

In some programs, FEMA relies on applicant self-certifications to avoid delays in payments, which increases the risk of improper payments and fraud.

Actions to Combat Waste and Abuse

OIG Audits and Reports:

The OIG conducts various audits and issues reports with recommendations to improve FEMA’s management of disaster relief programs.

GAO High-Risk List:

The GAO identifies areas like FEMA’s programs as high-risk operations vulnerable to waste and abuse, highlighting the need for transformation and improved oversight.

DHS OIG COVID-19 Fraud Unit (CFU):

A dedicated unit was established to investigate fraud related to COVID-19, with findings from audits being passed on for further investigation.

Reporting Mechanisms:

The public can report suspected fraud, waste, or abuse through the DHS OIG Online Allegation Form or the FEMA.gov disaster fraud page.

Pogo says

@maga midgets

Get busy on the audit of Trump’s crypto fraud, and self-dealing with the scum of the earth; here’s a simple start:

All pigs are equal, some more than others

https://www.google.com/search?q=audit+of+Trump's+crypto+fraud%2C+and+other+self-dealing

Sherry says

This from the New Republic:

Late on the evening of January 17, when most presidents-elect are wholly focused on the immense task before them, Trump found the time to post a jolly advertisement on his Truth Social website:

“My NEW Official Trump Meme is HERE! It’s time to celebrate everything we stand for: WINNING! Join my very special Trump Community. GET YOUR $TRUMP NOW.”

Festooned with an image of him brandishing his fist and the words FIGHT FIGHT FIGHT, which adorn the $TRUMP memecoin, the post directed supporters to a website where they could buy their very own—as hundreds of thousands promptly did. Within hours, the virtual token had gained a market capitalization of more than $7 billion; by early the following day, its sales price had soared by more than 500 percent, with a face price of $30 and a market value, on paper, of roughly $30 billion.

With the Trump Organization and its affiliates holding about 80 percent of the Trump meme coins (including a second token dubbed $MELANIA that also enjoyed a stratospheric launch over inaugural weekend), it seemed there would be no more scoffing about the billionaire status of the once (or twice, or six times) bankrupted real estate mogul. Suddenly Trump was inching closer toward the kind of incomprehensible wealth of a Buffett, a Gates … or a Musk.

The Trump coin quickly diminished in value, only to briefly rocket back up in late April when its website promised an “intimate private dinner” with the president for the top 220 coin buyers, and a “Special VIP” White House tour for the top 25 customers.

Yet the promotional materials and the astonishing early numbers posted by $TRUMP obscured the basic fact that this new memecoin, like most forms of cryptocurrency, has no inherent worth at all. It isn’t an actual coin, of course, and its virtual existence is nothing more than an opportunity for speculation. Nobody knew this better than Trump, who told Fox News years ago that he suspected cryptocurrencies “may be fake” and Bitcoin was “a scam” used by drug gangs, as well as a potential threat to the dollar and U.S. national security. But that was before his sons Eric and Donald Jr., both crypto enthusiasts, persuaded him that instead of being a crypto mark, he could become a digital pirate himself.

Trump learned what his elder boys meant in late 2022, when he made an initial foray into the blockchain economy online, shilling his own assortment of “non-fungible tokens,” or NFTs—a set of digital doodads that featured heroic images of him in comic-book style as an athlete, a soldier, and a superhero. So conspicuously trashy were these items (and Trump’s manic hawking of them) that even Steve Bannon protested. But Trump pocketed over a million dollars from their sale, even as their price eventually crashed and left other buyers at a loss.

On the eve of his ceremonial oath-taking, Trump’s crass display of greed appalled the nation’s leading crypto investors. Speaking off the record, some feared its impact on an industry that already wears a reputation for fraud, opacity, and criminality. “It’s absolutely preposterous that he would do this,” Nic Carter, a partner at a major crypto investment firm (and strong Trump supporter) told Politico. “They’re plumbing new depths of idiocy with the meme coin launch.”

Sherry says

Consider the possibility that it’s likely that most FEMA corruption is at the state level.

Therefore, federal oversight and regulation of FEMA monies is extremely important. However, with trump’s DOGE gutting the agencies that provide that regulation and oversight, just how is the corruption going to end?

Pogo says

@Sherry

Consider the fact, the official record, etc., of all the Republicans who’ve voted no for helping fellow Americans.

That’s my time. Have a good one.

Sherry says

Right ON POGO!