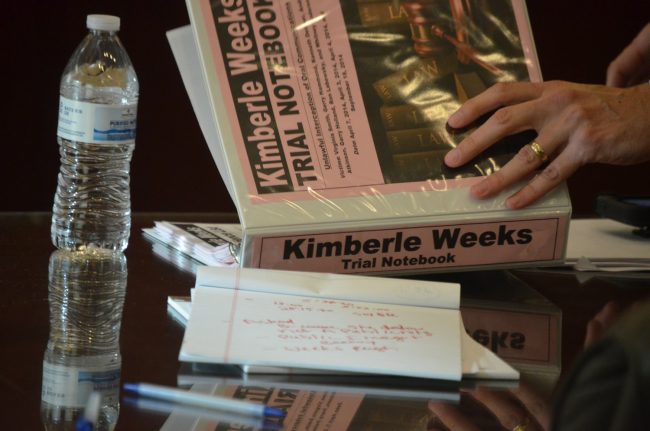

The prosecution rested in early afternoon Wednesday, the third day of the trial of Kimberle Weeks, the former Flagler County Elections supervisor, on felony charges that she illegally recorded a half dozen public officials without their consent.

In a surprise, the defense announced it would not put on a case.

It was a significant reversal that indicates abandonment of an earlier hint at a strategy. On Monday the defense said its witness list included County Commissioner Charlie Ericksen, County Attorney Al Hadeed, County Judge Melissa Moore-Stens, and Duane Weeks Sr., Kimberle’s husband, none of whom will now be called (to the certain relief of all those not called, though it appears Hadeed and Ericksen had never received summonses, according to a county official).

Based on the defense’s opening arguments, the defense was going to attempt to show that what had motivated Weeks to record others was revealing foul play by others. One of the conversations she’d recorded involved Hadeed and Ericksen. Weeks claimed there’d been foul play by an unnamed county commissioner on the canvassing board years before, that Hadeed and Ericksen talked about it in that conversation she recorded, and that defense attorney Ashley Kay started characterizing in her opening arguments.

But the prosecution immediately objected, saying none of it was the issue at trial. The issue was Weeks secretly recording others. “Trying to bring that in is an end-run around that evidence,” Assistant State Attorney Jason Lewis argued of the Hadeed-Ericksen matter to Circuit Judge Margaret Hudson. “It’s an end run around everything your honor, and they’re trying to make a mish-mash of everything.” Lewis’s argument carried.

By dispensing with putting on a case, the defense stuck to a different strategy that it focused on through the two days of trials: showing Weeks as acting in her capacity as a public official, doing the public’s business, when she was recording others without their consent. She was doing so because, in her lawyers’ view, she legally could as long as it was public business.

It’s a risky strategy that banks on the jury’s haziness about what is public and what is private business, what is a public meeting and what is not, even when those involved are all public officials. Hudson added to the haze by refusing to let either side define matters central to the case: what amounts to a “public meeting,” and what amounts to a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” Hudson’s ruling was inexplicable, other than that the two sides had radically different interpretations of the terms, and that she was leaving it up to the jury to decide–and define those terms. Hudson went so far as to bar the prosecution from letting one of its witnesses explain the law even though the witness is an expert in the Sunshine law–Gerry Hammond, a former attorney at the Attorney General’s office whose job was in part to write opinions about the Sunshine law.

That lack of definitions turns out to be the defense’s best hope, because placed in the jury’s hands, it’ll be less about the law as defined in court than about how the jury will interpret what’s been left undefined regarding public meetings and private conversations by public officials. Ironically, the strategy is vintage Weeks: as supervisor, Weeks was notorious for flouting the definitions of law and legal interpretations of platoons of lawyers, brandishing her own as the only valid one. Her lawyers appear to be doing the same thing on her behalf, turning her irreverence for established law into an argument and hoping the jury buys it.

The defense’s strategy may have its dividends. But it’s also risky, given the way the last two days have unfolded before the jury’s eyes.

In many ways the story of Kimberle Weeks has been the same story playing on a loop year after year for the past 10 years. The trial has been all about that loop, amplified and stripped of the muzzle Weeks had kept on a key part of the story: the conversations she secretly recorded Nixon-style, all but one over the phone.

Her tenure as Flagler County’s elections supervisor between 2009 and early 2015 was one of a public official chronically aggrieved with all other public officials and governments she interacted with, from county commissioners to Palm Coast government to state officials. Her defense following her indictment on criminal charges in 2015, just weeks after she resigned, has been framed to portray a lone public servant wrongly accused of committing crimes when, at least in her attorneys’ interpretation, she was doing the public’s business, valiantly holding others accountable, pointing out their wrongdoing, and breaking no laws, even when she was recording others without their consent.

In sum, everyone else was wrong. She was right.

Her trial has been playing that tape on a loop day after day–metaphorically of course, but also literally. The prosecution has played a half dozen or so of the conversations Weeks secretly recorded, conversations that mostly featured Weeks’s voice in long, breathless rants, most of them stream-of-consciousness dissertations that mix grievances with accusations, indictments, legal conclusions, demands, rebukes and ridicule, none of them displaying so much as a hint of humor, compassion or understanding regarding the innumerable public officials subject to her indignation, including those at the other end of the phone line. She does not come off well. She comes off as the Kimberle Weeks persona that jarred the local political scene for so many years, and as one so self-conscious of the role she was playing that she was recording conversations as a defense mechanism, if not as an entrapment mechanism (as was the case with the Ericksen-Hadeed conversation).

The defense is hoping the jury will only see the crusader, not the schemer the prosecution is portraying. But the evidence has been on the prosecution’s side, with the defense only countering it with a recasting of the evidence in a light more favorable to Weeks, and dependent on that novel, out-of-left-field interpretation of private conversations by public officials as automatically public business, open to recordings without permission.

This third day of trial, the second involving witnesses and evidence, was a repeat of the second day, with witness after witness speaking of the way he or she was recorded without permission, and with the prosecution playing many segments from those tapes. Most of the content of the tapes was actually not relevant to the prosecution’s case since it only took a few seconds to establish who was on each tape and whether the person being recorded had given permission.

But Lewis, who is prosecuting the case with Charlene Sullivan–and seems to relish his tactical skills–knew that his strongest witness for his case was the one he could not put on the stand: Weeks herself. And he knew that if he played as much of the tapes as possible, Weeks would be a witness against her will, and against herself, in the eyes and ears of the jury.

So it’s been. The tapes played in court over the past two days represented a sliver of the Weeks story but nevertheless looped listeners back into that whirlwind of Weeks years past, when she brought the same mix of indictments and indignation to public meetings, canvassing board meetings, county commission meetings or to the single-spaced reams of written theses about others’ wrongs she would allegorically nail on any door she could, as long as the doors opened to some kind of audience. (Her years as supervisor never reformed so much as repulsed officials she interacted with, but that historical context, like so much else, was not part of the trial.)

Weeks is not on trial for her character. But she is on trial over her conduct as a supervisor of elections, because every one of the secretly recorded conversations took place while she was supervisor. Her attorneys say none of the recordings involved anything but public issues, none of them involved secret or privileged information, all of them, with one exception, dealt with election matters relevant to public concerns.

Her attorneys never say that Weeks recorded those conversations secretly and kept those conversations as her own rather than as public records, refusing to turn over any of them (a few chosen snippets aside) even when requested through public records, whether by reporters, by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, by Palm Coast government officials or by county officials: they were all denied recordings of public meetings Weeks had made, a violation of Florida’s open-records law none of those denied pursued legally. Only a warrant and a search of multiple hard drives, computers her cell phone and thumb drives yielded the trove of conversations.

Rather, her attorneys interpret all those conversations as being no different that “public meetings,” and therefore conversations subject to public-meeting laws, where recordings are permissible without permission.

It’s a reach, and her lawyers likely know it. But they made the claim again today, either in direct arguments with the judge, out of the jury’s hearing, or by implying it as they asked the same questions of witness after witness: were you employed in a public function? Was your office a public office? Were the conversations you had with Weeks all involving public matters?

The witnesses had to answer yes in every case. The witnesses today included Palm Coast City Clerk Virginia Smith, Hammond of the Attorney General’s office, Ron Labasky, the attorney representing the state association of elections supervisors, and Shannon Brown, the only non-public official whose recording is part of the prosecution’s evidence, and who spoke by video from Michigan: Weeks had recorded their conversation about Brown’s ex-husband, who was then dating Weeks’s daughter, much to Weeks’s displeasure. “I want to stop this girl from marrying this idiot, I think this is a train wreck waiting to happen,” Weeks is heard saying in a milder part of the tape. Again, Lewis played the tape more to reveal Weeks’s character than to add to his evidence.

The defense had attempted to keep the tape out of the trial but failed. It did not detract from what was by then its only argument: the claim that any conversation between any two public officials on any public matter, including conversations on legal issues with government lawyers, are the same as public meetings. Under that interpretation, any citizen could walk into any government staff meeting, listen in in on any phone conversation, crash any discussion behind closed doors between any two officials, and do so legally.

That’s not what the law says. Not even close. Nothing in Florida’s expansive sunshine law makes such permissive provisions even for routine discussion between officials outside of advertised public meetings (as long as the officials are staffers or don’t include two elected officials from the same board).

Kevin Kulik, the defense attorney, toward the end of the day pointed to a Third District Court of Appeal decision from 2004 in which one party secretly recorded a business shareholder meeting involving several individuals. One of the individuals sued, saying it was a violation of Florida’s prohibition. A lower court dismissed the case and the appeals court affirmed the dismissal. To Kulik, the case is proof that even a private business meeting may be recorded legally.

But he did not mention one detail that the ruling makes clear, and that demolishes Kulik’s theory: the case was thrown out because it invoked a Florida law while “the plaintiffs are not Florida residents, the taping was not alleged to have occurred in Florida, and the recordings were not alleged to have been disclosed or used in Florida.” It wasn’t that the plaintiffs didn’t have a case. They had no standing. There’s no parallel with the Weeks case.

Still, that’s what the defense will be arguing to the jury Thursday morning, concluding that Weeks, in such a context, had every right to tape the conversations.

The prosecution’s retort will be a more sophisticated, more legalese version of the age-old concept of are you kidding me, a version Lewis, who combines the geniality of an Everyman with an AR-15-like verbal delivery (and the inevitable powerpoint) is unusually suited for, assuming he closes either part of the prosecution’s two final arguments. (The prosecution goes first, the defense follows, the prosecution then gets the last word. There’s no time limit.)

What has been a 10-year spectacle of the Weeks loop may end Thursday, starting at 9 a.m. in Courtroom 401 at the Flagler County courthouse. Appeals, of course, are always possible.

Fredrick says

It is refreshing to see Kimmy in the news again.

smarterthanmost says

Florida is known for it’s stupid juries, let’s hope this isn’t one of them.

daddybear says

put her in jail thats where she belongs!