By Richard Thomas

Within a congested sporting summer, we might have already witnessed the most unexpected sporting moment of 2024. In what has been dubbed “one of the biggest shocks in cricket history”, the ICC Men’s T20 World Cup co-hosts USA beat Pakistan in a pulsating game on June 6. With seven runs needed off the last ball of a “super over” tiebreaker, Pakistan could only manage a single.

Few saw this coming. Pakistan has significant cricketing pedigree, including winning this tournament in 2009 and finishing runners-up in 2022. Cricket is also hardly a mainstream sport in the US. Indeed, the New York Times suggested that many Americans were “oblivious to the magnitude” of the victory.

But history suggests perhaps it should be less of surprise. After all, the first ever international cricket match took place in what is now Manhattan, with the US losing a low-scoring game to Canada in September 1844. And when the Philadelphian cricket team visited England in 1897, 1903 and 1908, they were good enough to win 12 matches against first-class counties at a time when English cricket was in its “golden age”.

Their star player, John “Bart” King, was among the most innovative bowlers of the era. His baseball-inspired bowling action and express pace proved too much for many hapless English batsmen.

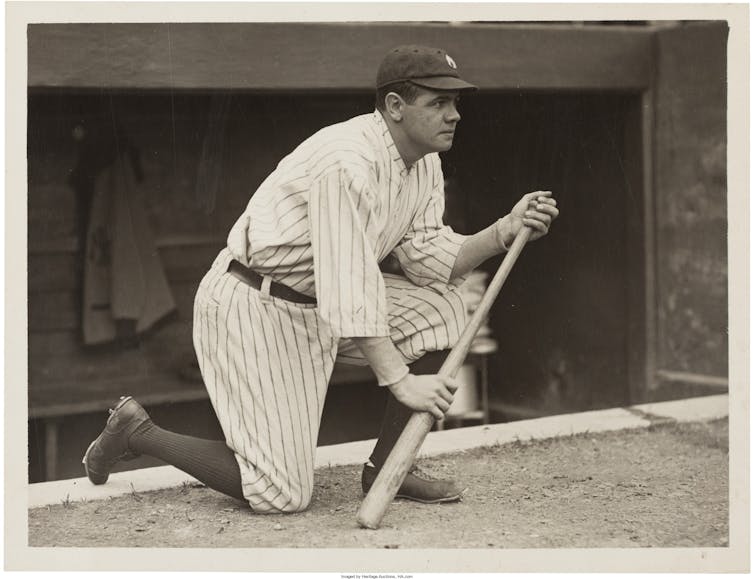

During a tour of Australian cricketers to North America in 1932, sponsors saw great promotional mileage in orchestrating an off-field meeting between the world’s best cricketer at the time, Donald Bradman, and its greatest baseballer, Babe Ruth. The “two greatest hitters of the moving ball” apparently hit it off, albeit the incredulous American was heard to ask: “You mean to tell me sometimes you don’t have to run when you hit the ball?”

Paul Thompson / Heritage Auctions / Wikimedia Commons

But if US cricket is to kick on following the momentous victory against Pakistan (and its preceding win against Canada), then the US game must move beyond continual negative comparisons with baseball.

Described by American comedian and actor Groucho Marx as “a wonderful cure for insomnia”, is cricket really too ponderous and long winded for American audiences, given that a baseball game takes nearly as long as a T20 match? The 200,000 Americans regularly playing cricket in 400 different leagues would argue that this version of the game is every bit as dynamic and exciting as baseball.

Cricket’s American dream

The traditional US diet of American Football, baseball and basketball is a difficult triumvirate to disturb. But the emergence of Major League Cricket (MLC) is at least daring to mount a challenge.

Now in its second season, MLC has six franchise teams (with more planned) and is already attracting many of the world’s best male cricketers. Australia’s star internationals Pat Cummins, Travis Head, Glenn Maxwell and Steve Smith will all participate in this year’s tournament, which starts on July 5, with fellow countrymen Mitchell Marsh (the current T20 World Cup captain) and Marcus Stoinis likely to join them.

The tournament overlaps with the UK’s still relatively new limited-overs franchise competition The Hundred. And MLC’s ability to draw private investment – and the higher salaries that will inevitably follow – means the American short-form game might prove more attractive to top players than the UK tournament.

While this all bodes well for cricket in the US, there are some operational challenges to overcome. The first is whether its administrative infrastructure can recover after the USA Cricket Association was suspended by the International Cricket Council in 2015 because of concerns regarding its “governance, finance, reputation and cricketing activities”. The old association had somehow found itself US$4 million (£3.15 million) in debt despite there barely being an established cricket ground in the country at that time.

This brings us to the next challenge: the quality of the grounds. However loud the hype and marketing, poor pitches – the central cut strip the game is played on – will always be open to heavy cricketing scrutiny.

Most experts agree that some of the US pitches being used for the World Cup are substandard. Indeed, the playing surface at Nassau County International Cricket Stadium in New York has been described as “bordering on dangerous” after a succession of low-scoring matches.

Ultimately, the future of US cricket is all about money. Will there be enough advertising, broadcasting and sponsorship revenue? And will it be used to pay marquee players to play on poor surfaces, or invested in infrastructure, facilities and grassroots development?

It seems unlikely that cricket will take long-lasting root in America until the game is played in schools and colleges, and women’s cricket acquires the momentum it has elsewhere.

More positively, a women’s MLC is already being discussed, and cricket will make an appearance in the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028. These are further significant platforms to expose the game to a wider audience – but time will tell how far it manages to squeeze itself into the national psyche and a sporting landscape steeped in history, culture and big business principles.

For now, though, team USA can only do what they are doing – win with style and terrify some cricketing titans into the bargain.

![]()

Richard Thomas is Professor of Journalism at Swansea University.

Leave a Reply