By Lucy Christopher

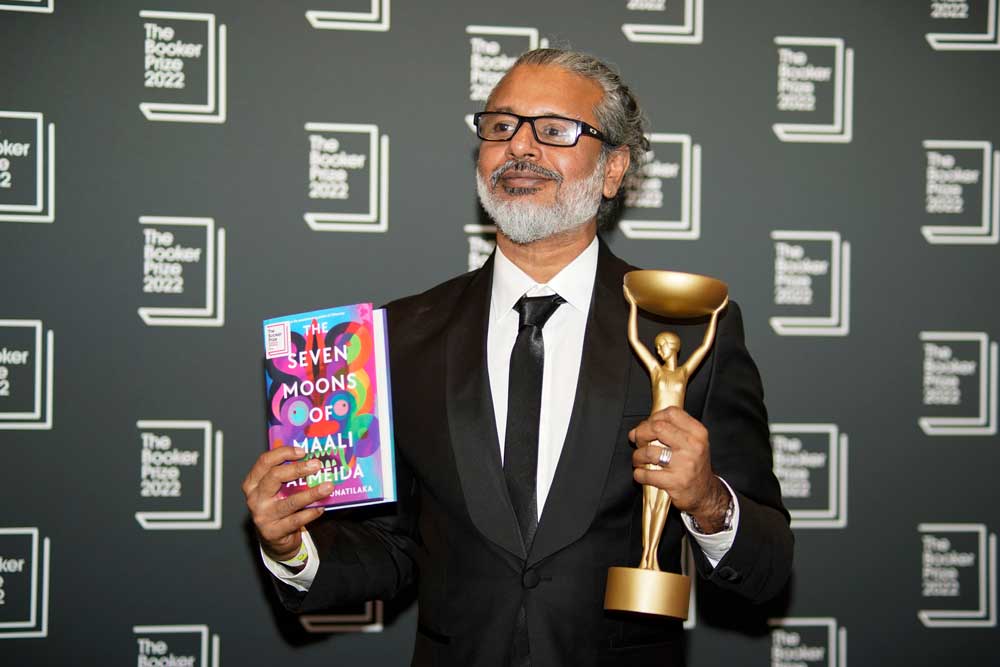

Sri Lankan novelist Shehan Karunatilaka has won the 2022 Booker Prize for his second novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida.

The win couldn’t come at a better time for Sri Lanka, a country once more engaged in political and economic instability, as it suffers through one of the world’s worst economic crises, with soaring inflation, food and fuel shortages, and low supplies of foreign reserves. And of course, the government was overthrown in July, after President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled following mass protests.

Karunatilaka said in his acceptance speech:

My hope for Seven Moons is this; that in the not-too-distant future, 10 years, as long as it takes, Sri Lanka […] has understood that these ideas of corruption and race-baiting and cronyism have not worked and will never work.

Political black comedy

Karunatilaka’s novel is extraordinary – and hard to pin down. It is at once a black comedy about the afterlife, a murder mystery whodunit, and a political satire set against the violent backdrop of the late-1980s Sri Lankan civil war. It is also a story of love and redemption.

Malinda “Maali” Kabalana, a closeted war photographer, wakes up dead in what seems to be a celestial waiting room. The setting will be familiar to many who’ve spent time in Colombo (as I have – it’s where my husband’s family is from). We open in a busy, bureaucratic office, filled with confusion, noise, a propensity against queuing – and a healthy dose of “gallows” humour. In other words, Maali is in some sort of purgatory.

Maali soon discovers he has seven days – seven moons – to solve his own murder. This isn’t easy – he is interrupted by sardonic ghosts (often with grudges, questionable motives, and a tendency towards extreme chattiness), the violent reality of war-torn Colombo, and piecing together his memories of who he was.

He also has seven moons to lead his official girlfriend and his secret boyfriend to a cache of photographs, taken over time, which document the horror of the war – and incriminate local and foreign governments.

Karunatilaka’s subject matter and plot highlight, question and explore Sri Lanka’s legacy – and its continued, difficult relationship with its civil war, which spanned 1983 to 2009, though the reverberations continue. And his novel’s provocative, intimate, second-person style implicates us – the readers.

Karunatilaka has mastered his craft as a novelist. He never once wavers from a second-person perspective that might be unwieldy (perhaps even gimmicky) in a lesser writer’s hands. The novel tells us, “Don’t try and look for the good guys, ‘cause there ain’t none”.

It realises a combined responsibility for the tragedy of that 25-year civil war, in which the country’s colonial history is also implicated. British colonialists brought Tamil workers from South India to Sri Lanka, to work as indentured labourers on their coffee, tea and rubber plantations. Their descendants’ fight for an independent Tamil state was a strong component of the civil war.

Diffusing violence with humour

As a novelist and lover of second-person narration and a long-time follower of Karuntailaka’s accomplished work, I couldn’t be more delighted by this Booker win.

I first came across Karunatilaka through his debut novel, Chinaman, which was handed to me by my sister-in-law several years ago on a family visit to Colombo. That book taught me about cricket, but it also taught me the sardonic brilliance of Sri Lankan humour.

Karunatilaka once again uses humour to great effect in The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida – to diffuse confronting moments of violence, to engage his reader, and for pure enjoyment. This novel follows a murder victim through a bloody civil war – and it’s laugh-out-loud funny.

It’s also a tighter, more focused book than Chinaman: here is an author in control of his craft and what he wants to say with it. The Booker judges, too, praised the “scope and the skill, the daring, the audacity and hilarity” of the book.

Karunatilaka’s winning novel took time to write. Ten years have passed since Chinaman. His skilful use of craft to tell this complicated story is testament to the idea that good books take the time they need: something that all authors know but publishers are not always willing to accept. However, Karunatilaka has been busy in that ten years, not just writing literary fiction, but writing for children – and having a family. The 47-year-old is now married with two kids.

Karunatilaka is only the second Sri Lankan novelist to have won the Booker Prize. (The first was Michael Ondaatje in 1992 for The English Patient.) But last year, his countryman Anuk Arudpragasam was also shortlisted, for A Passage North, another accomplished novel set in the aftermath of the civil war.

I’m excited by what this means for Sri Lankan authors and the Sri Lankan publishing scene. Here is a country with stories to tell and enormous skill to tell them with: let’s hope this leads to more Sri Lankan novels achieving wide readership, success and deserved acclaim.

![]()

Lucy Christopher is Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Tasmania.

Leave a Reply