By Fran Brearton

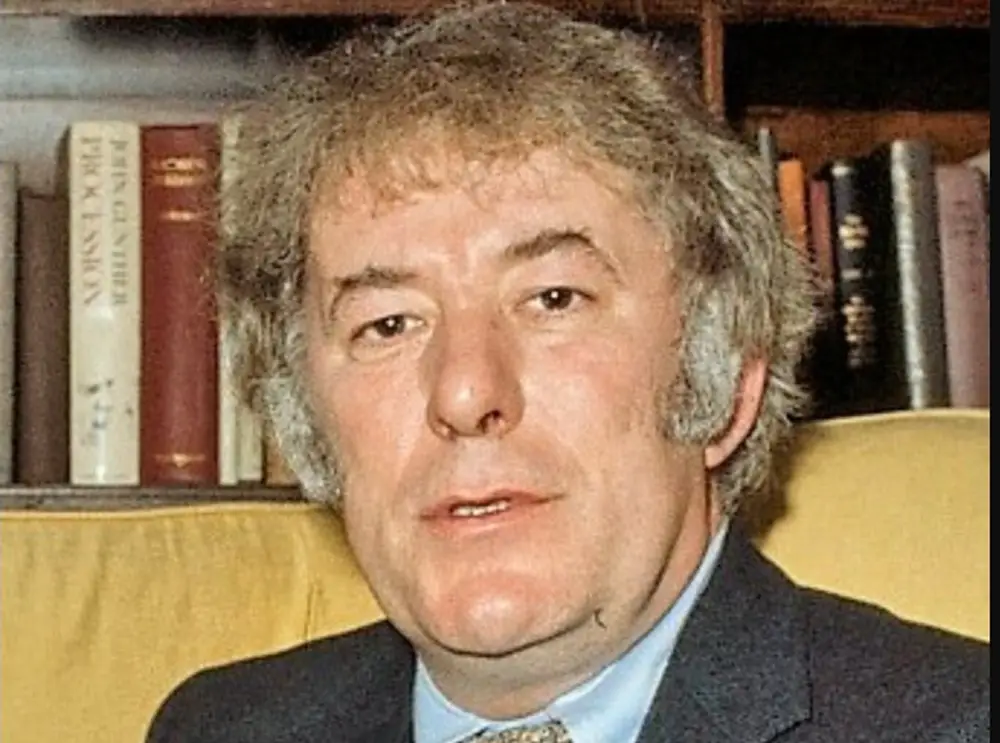

The English war poet Wilfred Owen once wrote, “Celebrity is the last infirmity I desire.” Killed in France at the age of 25, unpublished and unknown, “celebrity” for Owen was a posthumous phenomenon. By contrast, celebrity status for the Irish poet Seamus Heaney – “Famous Seamus” – came early in his life.

The eldest of nine children raised on a small farm called Mossbawn in County Derry – which was so crucial to his imaginative development – his first collection, Death of a Naturalist, was accepted for publication by Faber when he was just 26.

Thirty years later, he became the fourth Irishman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, following Shaw, Yeats and Beckett. By the time of his death in 2013, Heaney’s books accounted for some two-thirds of the sales of contemporary poets in the UK.

Always conscious of Owen’s example, as well as Yeats, Frost or the Romantic poets, Heaney shares with them all the unusual capacity to reach a much larger audience than poetry generally enjoys.

Readers felt his death in 2013 as a personal loss, bereft as they were of a familiar and intimate voice that had accompanied them through half a century’s life of writing, with Heaney’s own story woven into the turbulent story of Ireland.

A life in letters

The recently published edition of Heaney’s letters, edited by poet Christopher Reid, is a marvellous addition for an audience always hungry for more Heaney.

Beginning with his “new life” in 1965 – marriage, house-buying in Belfast, manuscript acceptance – it bears witness to what Reid calls “the sheer outward-facing busyness” of Heaney’s life. It was a busyness that brought, alongside celebrity, increasingly obvious pressures on a poet always generous with himself, his time and his work.

It’s unsurprising that as his fame grew, so too did the demands made on him. And as writer Bel Mooney noted recently, although “all of us who wanted a piece of him could have been fobbed off”, he was “just too nice”. The letters – abundant and revelatory, evidencing, as Reid puts it, Heaney’s “delight in his own fertile rhetoric” – are a treasure trove of delights for the reader.

But they prove Owen’s point about the challenges of celebrity, too: “Excuse the stationery … this jotter is to hand”; “Please forgive me for not being in touch”; “Please excuse the pencil, I’m on the plane …”; “You deserved to hear from me before this”; “Hurriedly, with love – Seamus”.

The generosity and warmth of the poet as a public figure is, of course, one of the reasons why he was and is beloved by many – not least those who, in huge numbers, encountered him in person through a lifetime of lectures, readings, workshops and launches. He once joked that one day his unsigned books would be more valuable.

Faith in poetry

That warmth and generosity came at a cost to Heaney personally, as he struggled to protect from public scrutiny those “whole areas of one’s life that one wants to keep free from the gaze of print”. He wanted to shield as well those elements of his “remembered soul landscape” that were the source of his inspiration – what Wordsworth termed “the hiding-places of my power”.

Protect them he did since it is, in the end, the imaginative generosity of the poems themselves, not the personal generosity of the man, that ensures his legacy. It does so in part because of Heaney’s faith in the poem – as answering to no agenda other than its own being, operating as its own “vindicating force”, undiminished by, and existing outside of, the noise and “busyness” of life.

In his 1995 Nobel lecture, Heaney spoke of poetry’s “gift for telling truth” – and beyond that, its capacity “to be not only pleasurably right, but compellingly wise”. It might even be “a retuning of the world itself”.

Few contemporary poets have devoted so much time to writing a defence of poetry as Heaney; fewer still have done so in terms so protective of poetry’s autonomy. Irish poet Leontia Flynn writes of finding herself “nearly as grateful for his defence of poetry as … for his poems”.

Heaney’s capacity to “credit marvels” in the world around him is, quite literally, the gift that keeps on giving. As he writes in his poem Fosterling:

Me waiting until I was nearly fifty

To credit marvels. Like the tree-clock of tin cans

The tinkers made. So long for air to brighten,

Time to be dazzled and the heart to lighten.

In one of his finest lyrics, The Harvest Bow, the “throwaway love-knot of straw” plaited by his father is echoed in the intricate weaving, “twist by twist”, of its harvest bow of words.

Its “golden loops” are a gateway to the past, and as we follow Heaney’s “homesick” memory of walking peaceably with his father, the beautifully crafted love-knot encircles and cradles an entire community and a way of life. The bow is a still a “frail device”. Like poetry, it is both transformative and under threat; but most importantly, it endures.

A decade after his death, Heaney’s voice, like the harvest bow, is “burnished by its passage, and still warm”.

![]()

Fran Brearton is Professor of Modern Poetry, School of Arts, English and Languages at Queen’s University Belfast.

Pogo says

@FlaglerLive

Thank you for putting this forward.

@Fran Brearton

You are, I dare say, pleasurably right — and compellingly wise yourself. This was a pleasure.

Thank you.