It’s the small Japanese watercolor from the early 1800s that now hangs in his dining room–a portrait of a nameless man and woman–that started Robert Wittman’s unique relationship with art. Unique, because unlike every other art lover who’s ever existed, only Wittman crowned a long career with the FBI by creating the bureau’s art crime division. Only Wittman, through that division, can justly claimed to have recovered stolen masterpieces worth some $225 million. And only Wittman has had the skill., the prose and the personality to then become a best-selling storyteller, drawing crowds to his appearances the way great paintings or sculptures on special exhibits do.

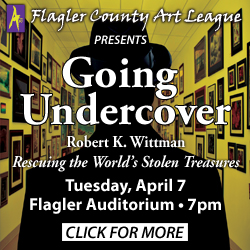

And thanks to the Flagler County Art League, Wittman will be telling his stories at the Flagler Auditorium next Tuesday (April 7), in a one-evening appearance that the league managed to secure as part of a fund-raising drive.

In a sense, he says, it is this “really unique little painting” and items like it collected in his home that bring his story full circle.

Wittman’s father, a Korean War veteran, acquired the small watercolor in Japan around 1950. He was an Air Force pilot stationed there at the time. Like many Americans in Asia, he “fell in love with all things Japanese, including my mother,” Wittman says. Returning stateside with Wittman’s mother and settling in Baltimore, Wittman’s father opened his own Asian antique shop. That was where his son remembers seeing the painting for the first time. That painting, and numerous other artifacts.

His extensive F.B.I education aside, Wittman says he owes much to his early time spent around those modest Asian works and those early memories. That was where he first cultivated his interest in what has been termed “cultural property.”

One of the higher-profile cases Wittman will surely discuss during his presentation April 7 is his Copenhagen rescue of a $35 million Rembrandt self-portrait from 1630, the only portrait Rembrandt ever did on copper. The painter was just 24 at the time.

The circumstances of that heist, which took place on a late afternoon around Christmas during one of the darkest times of the year, have been recounted many times over in far-reaching national publications and are all but legendary at this point: the band of three machine gun-wielding Iraqis storming the museum in the wake of several car bomb detonations on each of the two of the main roads leading to the museum; the thieves then making their escape via speedboat, with two Renoirs in tow as well. And the Rembrandt, the Stockholm’s Swedish National Museum’s crown jewel, gone.

The circumstances of that heist, which took place on a late afternoon around Christmas during one of the darkest times of the year, have been recounted many times over in far-reaching national publications and are all but legendary at this point: the band of three machine gun-wielding Iraqis storming the museum in the wake of several car bomb detonations on each of the two of the main roads leading to the museum; the thieves then making their escape via speedboat, with two Renoirs in tow as well. And the Rembrandt, the Stockholm’s Swedish National Museum’s crown jewel, gone.

The notorious Rembrandt case concluded when, a few years after the initial heist, the criminals, still unsuccessful in finding a buyer, and Wittman—posing as an art authenticator for the Russian mob—managed to orchestrate a $250,000 deal for the estimated $42 million worth of stolen art. He ended up meeting with the gang face-to-face in a Copenhagen hotel room. There, once all the “i”s were dotted, he said “we have a done deal,” the signal for the swat team in waiting in the adjoining room. It’s an unbelievable story, not least because the ingenuous bandits with the grandiose ambitions were, ultimately, willing to settle for such a paltry sum for such high-valued assets.

“That’s the thing about these criminals,” Wittman says. “They’re good criminals because they know how to do a heist, but they’re terrible businessmen. And what they don’t understand about the art world is that it doesn’t make any real sense to steal art. The three things that make art valuable are the history, the authentication, and the good title. If you’ve stolen the work, you don’t have the good title and then you don’t have good value.” The $35 million appraisal is just a number in the sky. “You’re not going to be able to get that kind of money because you can’t sell the piece in the proper channels.”

In one of Wittman’s first major cases, he succeeded in recovering a large crystal ball formerly owned by the Dowager Empress of China, Cixi (1835-1908.) for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology. It was after that, that the bureau felt they had a niche for Wittman and therefore paid for him to undergo a comprehensive art education program. That included fine art studies at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation, Santa Monica’s Gemological Institute of America, commonly known as GIA, a non-profit gem research institute. They also had him put in time at the Zale Corporation in Dallas where he was sent to learn gemological identification. Once Wittman graduated, he assumed the title of the Bureau’s high asset value expert for “gems, antiques, antiquities—that sort of thing.”

Yet, it was Wittman’s education in his father’s store that proved to be the most valuable. That was what gave him a leg up over the bad guys in the process of gaining their trust: The knowledge of how to build a rapport and get to know your customers; the ability to close a deal. It was those matters that made all the difference. “So the important part of being an art theft investigator is I knew how to do a business deal in the art world,” Wittman adds. “That’s a big plus when you’re working undercover in art investigation.” His unique cultural background also put him in a position to understand different cultures, which facilitated his ability to be able to discuss different types of art: “whether it was Asian art, Pre-Columbian, antiquities from the Middle East, whatever it would be.”

Trying to recover a Picasso stolen in an armed robbery from the Fine Arts museum in Nice (where several other works were also stolen) Wittman assumed the role of a Colombian drug cartel member. The criminals were ultimately caught in Marseilles with the paintings in their car along with hand grenades and machine guns. Wittman seems never to have nee fazed by these close encounters in art’s underground. He ascribes his calm to having “a bit of an edge. It’s not nerves, it’s more just being focused. When you do that, it’s something you need to have to be able to work undercover successfully that way.”

Wittman relates these stories in his book, “Priceless: How I went Undercover to Rescue the World’s Stolen Treasures,” a gripping narrative that inspired Joyce Gatonska, the Flagler County Art League’s director-at-large, to reach out. The league’s relatively recent book club had chosen “Priceless” as one of its monthly picks. To Gatonska, it read like a movie script, she says. “You know, you see this man sitting on this yacht in Miami with all of these F.B.I agents who’re posing as something else. And then you read about him in the bathroom in Europe holding a Rembrandt painting to his chest, and throughout the book reading about these experiences that are remarkable.

“If you’re a lover of art, it’s wonderful to know these things were recovered,” she continued. “But I think what struck me the most, besides recovery of the artifact or the painting itself, was that the cultural history was what he was trying to rescue.” He wasn’t just trying to put someone in prison. “The goal wasn’t the criminal; the goal was the piece. That the history and the value of what it means culturally to any society is what’s really important.”

Preparing to lead the book-club discussion, Gatonska Googled Wittman, found his bio, saw that he did speaking engagements and gave it shot. It worked: She landed the gig. Wittman called her back himself within days. “He feels so strongly about the importance of art and culture in the community that he really wanted to make this happen for us,” Gatonska says.

He’s not coming for nothing: it’s costing the league $11,000 to put on the Wittman program, though this week the league got a $3,000 grant from Palm Coast, it got a $2,500 grant from the county earlier this month, and Local Realtor David Alfin is covering almost the entirety of the rest, which means everything the league raises from ticket sales to the event, and other proceeds, will go into its fund-raising kitty. (General admission tickets are $20.) Wittman will also be making a special presentation to high school students, at the auditorium, during the last period of the school day on April 7, at no cost to the students of course. (Just last week 14 students at Flagler College in St. Augustine accepted jobs with the FBI, the college announced last Friday, but none, it appears, are heading into the art-crime division as of yet.)

Although he didn’t know in the beginning that he’d be heading down this art recovery path, specifically—he’d studied political science in school—Wittman realized early on that the bureau would be a good fit for him. “I thought it’d be a great place to work because I was always interested in protecting people’s rights and civil rights and sorting out public corruption, so I always thought it’d be a very interesting and honorable place to work.”

Again, this leaning harkens back to early family memories, particularly those involving his Japanese mother.

At that time, in the early 1950s, “there was still a lot animosity against the Japanese because World War II wasn’t that far in the past,” he says. “And I remember walking down the street and people hurtling insults at my mother. And I always thought the place to be to protect against that and make sure that doesn’t happen would be with the F.B.I because they were doing civil rights investigations at that time in Mississippi and the Deep South. And knowing that, I always thought that’d be something of interest to me to be involved with as well,” he says.

Wittman retired from the bureau in 2008. He decided to write a book compiling his experiences that took him to more than 20 countries over the course of his career. “I didn’t want to just write a book that was not specifically criminal, or true crime, or just academic. I wanted to write something that people would enjoy reading but at the same time get some understanding of how important it is to protect our cultural property and how, once it’s gone, we lose a piece of our heritage,” he says.

He also hopes the art crime team—credited with recovering more than $150 million worth of art and cultural property—could benefit from the exposure by getting bigger budgets through Congress, he says. Before the team was created, art crime was seen as just another form of property crime. In other words, “they equated a Monet as being the same as a Chevrolet,” he says. “I had to say it’s not the same thing. The loss of cultural property has more of an impact than simply property in general. It should have a different type of investigative prominence.”

A perfect illustration might be a stolen Comanche headdress with eagle feathers. Or what Wittman calls a “blood flag.” The blood flag was carried into battle in the Louisiana woods by one of the first African-American regiments of the Union Army. It earned its moniker because five of the men carrying the flag were shot down underneath it, he says. It had been stolen from the United States Army en route between two forts during the 1970s.

Posing as a London antiques dealer, Wittman caught up with the individual then illegally in possession of the Civil War heirloom. The man claimed to have bought it from another individual at a Civil War show, right out of the trunk of his car. “Afterwards, we found out that that probably was not true,” Wittman says. The man was arrested and incarcerated on the charge of interstate transportation of stolen property, though he wasn’t thought to be the original thief.

To Wittman, there’s no difference between an item like the flag or a priceless painting, despite disproportionate monetary values. “It’s cultural property to our nation,” he says of the flag. “A piece of cultural property is just as important as a Picasso in a national gallery.” In the end, these items are really only valuable because of what they mean to us, he says.

It’s the same with that “unique little” painting hanging in his dining room. According to Wittman, 59, the painting “has great sentimental value and I don’t think it’s worth that much, but it’s worth a lot to me from the standpoint of my background and upbringing,” and his parents, of course, he says.

![]()

“Going Undercover: Rescuing the World’s Stolen Treasures”: Robert Wittman at the Flagler Auditorium, Tuesday, April 7 at 7 p.m. General admission tickets are $20, with a book sale and signing following the presentation. Tickets for a VIP private reception beginning at 5:30 p.m. are $60 and include a signed copy of Wittman’s book “Priceless.” Call the Box Office today at 386-437-7547 or order tickets online here for general admission, and here for the private reception.

Leave a Reply