For a last patrol at the end of Undersheriff Rick Staly’s 40-year career in law enforcement, it was anticlimactic Friday evening: a pair of lost tourists driving the wrong way off an I-95 on ramp, a woman with prior convictions getting yet another DUI off Boulder Rock Drive, word of a fight by the side of I-95 that turned up nothing, a wreck in the Mondex.

That was about it in six hours of patrolling until nearly midnight as Staly, who retires next Friday (April 17), was doing for the last time what he’d been doing since becoming an 18-year-old police officer in Oviedo in 1974.

It was just as well. One of the reasons he moved to Flagler is the quiet. It’s the sort of place where, at Bob Evans restaurant for instance, where Staly stopped for dinner Friday, a waitress immediately saw his uniform as an invitation to chat him up, ask him whether he knows Cpl. Eric Allen, whose son she dated, tell him to send him her greetings.

“This is a very different county, it’s a much friendlier county for law enforcement than Orange County actually today, not in the beginning of my career,” Staly says after the encounter. The quietness of the police radio that evening made his point. It reminds him of his early days as a cop in snoring Seminole, in contrast with his latter days in fickle Orange. “My historical perspective is Orange County. I’d go out on a Friday night like this and the radio would never stop.” It’s quiet enough that he can hear the faint lyrics of jilted love and Southern anthems on KIXS Country in the background. “I remember first coming here, it was like, is my radio working? Because it’s so quiet. That’s why we love it here and why people want to live here, because we don’t have the crime that other communities have.”

The unspoken parallel is that if Flagler today is the way Seminole seemed 30 years ago, will it go the way of Orlando as it keeps growing toward its supposed population of 200,000, or 250,000? “I hope not,” the undersheriff says. “I think the key is to stay on top of the issues when they crop up, so if we start getting serious gangs, then you’ve got to stay on top of them and basically knock them down, they don’t want to do business in Flagler County, because once they get a foothold, you’ll never get it back. You can look at the city of Orlando as a prime example. They had chiefs there that would never admit they had a gang problem.” Until they had one.

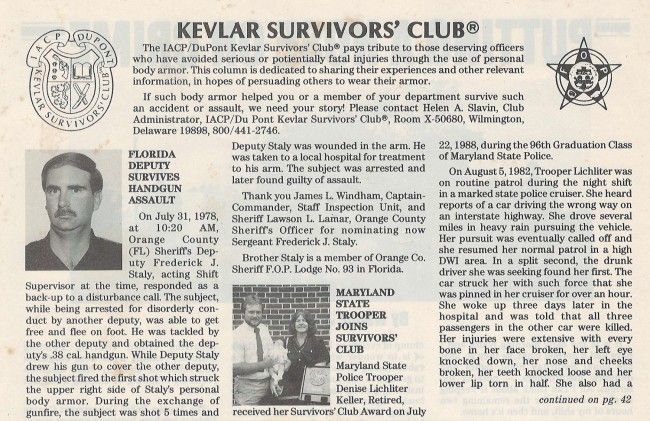

Staly’s had his share of action, including getting shot three times in a July 1978 confrontation with a man later convicted of attempted first degree murder: a $250 Kevlar vest he’d paid for himself saved his life. The incident left its marks, not only in the two places on his right arm that bullets penetrated, or in his chest, where the force of the bullet cracked two ribs despite the vest. He saw his life end down the barrel of his assailant’s gun, the gun ripped off the cop who was supposed to have been backing up Staly. He heard the shots that were supposed to end his life, and for a moment hadn’t realized that they were from another gun that felled the suspect, who was shot five times. And survived. Staly was treated and released that same day. He went on not only to survive in the Orange County Sheriff’s Office as it kept pace with one of the fastest-growing regions in the country—it added 50 to 60 new deputies every year in the 1990s—but rising to undersheriff by 1993, and falling short of becoming sheriff himself by a few points. He had challenged his ex-boss, Kevin Beary, who was under a cloud of ethical issues. Beary outspent Staly 6-to-1 and won with just 53 percent of the vote. The cloud dispersed after Beary’s re-election.

If there’s a sense of déjà vu in all this, it’s because there is. The social media gossips, the corridor chatters, the armchair analysts aren’t inventing anything when they see the re-run of an undersheriff working for a sheriff facing his own ethical matters before the Florida Commission on Ethics, or an undersheriff retiring at a time propitious enough to make it seem like a retirement, but also early enough to prepare for a more seasoned run at an old objective. To better know Staly’s history is also to understand that, should he choose to run, he wouldn’t be running against Jim Manfre, but to reach the one goal that’s eluded him most.

Staly says he’s focused on retirement now. He’s 59. But he’s retired twice before. Friday will be his third. It’s difficult to imagine it’ll be his last. He loves the job. Aside from a stint as the senior vice president for security for the Ginn Companies in Celebration, then as owner of his own security firm—American Eagle Sentry in Palm Coast after leaving the Sheriff’s Office in Orange, he’s never been far from the job. Even then, he was a reserve deputy in the Seminole County Sheriff’s Office.

As many candidates are expected to run for Flagler County Sheriff then as are expected to run for president. Rumors persist that Staly will be one of them. He never gives an outright no about it all. He just doesn’t address it directly.

“I know there’s a lot of speculation out there,” Staly says. “It’s my third retirement, a lot of friends said we’ll believe it when we see it, so my track record isn’t too good for not coming back to work or doing something, but I have some investments I’m working on, and then we’ll see what the future holds after that. But that’s really as far as the planning that I’ve done for my future.”

As a man who values investments, he surely knows the value of his last two and a half years–and he takes very seriously the accomplishments he’s managed with Manfre, which he doesn’t want undone by an administration with a different perspective.

Always a Cop

For now, his mother is 94 years old and very frail, he’s doing an RV trip with his wife, and expanding vacation rental properties he owns in the Tennessee mountains. Parry with him all you like: he fends off inquiries diplomatically and patiently. It was just as clear Friday evening that politics were not on his mind. Looking over his career was, back to the days when as a young boy playing in the neighborhood—he doesn’t remember this, but his mother told him of it—he’d pull over his friends. “I’d be on my bicycle riding around and pulling over the neighborhood kids. I don’t remember doing that,” he says of his Winter Park youth. “I do remember that I drew a little, on a piece of cardboard, a little police radio, a mike and all that, and I had that taped to my handlebar. I remember that. I don’t remember pulling over the kids that I played with.”

Always a cop.

There are deeper connections with public safety in his DNA. His mother, Jane Staly, a social worker with a master’s in health and a child of the Depression, implemented the Baker Act in Orange County when the law was first passed, and worked as the only non-Jew for Jewish Families and Children Services. She was and remains an ardent liberal, marching for causes—Staly remembers marching with her against police brutality in Jacksonville—joining protests and wearing an Obama button before anybody gave Obama a chance to win the presidency. “Two years before the Great recession, she predicted it,” Staly says. “One hundred percent nailed it.” He wishes he’d listened to her. He didn’t, and his investments took a beating.

Staly himself is no liberal. He considers himself a moderate Republican. He holds strong beliefs, but doesn’t preach them. Drums aren’t his style. Even his diction is calm, measured, settled. But those beliefs can nonetheless seem less than moderate. He blames social breakdowns on the breakdown of the family, on the end of prayer or the recitation of the Pledge in schools or the end of military service. He and Manfre, a Democrat, have their debates on various issues, from drug legalization to social policy. Staly can’t explain the disconnect from his mother’s politics, other than that he wasn’t too interested in politics as a young man. The extent of it was the length of his hair when he was at Terry Parker High School, which didn’t last: when the dean pulled his hair and ordered him to have it cut, he soon complied. He didn’t follow the convulsions of Vietnam or the Nixon White House, except that he began his career as a cop the very month Nixon resigned. After that, he was just interested in being a cop. Maybe he took his politics from his conservative father, a cabinetmaker who became very successful, but who also faltered in financial missteps. (His parents divorced when he was 12, his father died in December.) He was working at a gas station in his late adolescence, pumping gas one day when he started asking questions of a youth deputy. The deputy invited him to a meeting. A career was born.

Getting Over the Rookie Stage

Not surprisingly, at least not in retrospect, Staly rose to youth deputy captain. His first paid job was as a dispatcher, and when he saw an opening for a police officer in Oviedo, he took it: a town of 1,900 people and one traffic light. His dad had to buy him his first gun and stash of ammunition. Before long he was with the sheriff’s office. That was back in a time when the forces were almost all-white, all-male, all brawn. Back when black officers were not allowed to patrol white areas and when one black cop was referred to as Big Foot. It was back in the day before SWAT teams and elaborate warrant-serving operations, when Staly would, by himself, go around the county, serving warrants and stacking his car with suspects, one after the other, leaving them in the car (in the cage) while he knocked on the next suspect’s door.

He wasn’t being a hot shot. It was just the way things were done. But he knows looking back he wasn’t a seasoned cop then. He remembers his own mistakes, like handcuffing a man in front of his children when he could have just as easily done it out of their view.

“It takes 10 years to really become a great cop,” he says. “When you’re a rookie starting out you only see black and white for the most part. Every traffic violator gets a ticket. You make an arrest for everything. You don’t give as many breaks, that kind of stuff. And then as you progress and you’re handling more calls, then you realize that if you write a single mom a $300 ticket that maybe you could have gotten compliance with a warning, but you didn’t, you probably just took food or clothing or something away from those kids also. So who did you really impact?”

He remembers pulling over a young woman in late December years ago, when he’d been in law enforcement about seven or eight years. She worked at Disney. She was a single mother. There were children’s items in the back seat. He gave her a ticket. “I got back in my car, and I felt bad for giving her a ticket, so I pulled her over again,” Staly says. He asked for the ticket back. “I said Merry Christmas and I voided the ticket, which cost a lot of paperwork. But I use that as an example when I talk to new deputies: look beyond the black and white. Could you get a compliance with a warning?”

That vaguely sentimental side of his may seem made up. It isn’t. Noticing a too-long wait for dinner at Ruby Tuesday last week, he started walking toward Bob Evans across the lot, then turned back–a very faint echo of that double-take with the single mother–took out the dinner coupons he’d printed earlier, to save a few dollars (“I’m going to be on a fixed income,” he’d explained), found a family of four with young children, and handed them his coupons.

Crime Theorist

Staly has always been interested in the evolution of law enforcement. He devoted his master’s thesis to the subject, and on Friday he spoke at length of law enforcement changes during his four daces as a cop.

“The nature of the crime has not really changed,” he said. “You’re still investigating and dealing with burglaries and thefts and sex crimes and robberies. That’s still goes on today. The difference now is, the laws are a little tougher, like domestic violence, for example. When I started my career you could not make an arrest for domestic violence battery unless you witnessed it. Now you can. So the laws have given us more tools in the toolbox to impact and behavior and crime. But what really has changed is that the violent offender is much more violent today. Just because you’re wearing a badge and you have a gun doesn’t stop them. I truly believe that. I see it. Now, our crime numbers are down. So there’s less of those crimes.”

So why the increase in violence? “The apple-pie America is declining,” he says, citing the breakdown of the family, and the elimination of more traditional values, the pressures of parents working multiple jobs, but also, surprisingly—and a bit disturbingly—the country “losing its identity.”

“Different cultures coming in that are bringing cultures from other countries that don’t mesh real well with some of the cultures in this country,” Staly says. “They bring a violent side of it. So you put all that together, and that’s what we have today. And one of the reasons there’s more violence is, when the family unit breaks down and children today, whether it’s teenagers or young adults, are not getting the attention that they want from their parents because their parents are working two jobs to make ends meet or they’re divorced, maybe the dad is gone or the mother is gone, they never see them, they’re looking for that parent figure, and that’s exactly what gangs thrive on.”

There are echoes of his current thinking in his master’s thesis from 1991. “Justice was simple” two centuries ago, he’d written then. “There were few laws and the laws that were codified were simple. Don’t kill. Don’t steal. Don’t rape. Lawmen and lawyers were sparse and citizens fended much for themselves.” It was never really that simple in a nation founded from its first colony on the notion of law and compacts, but you get the idea: Staly embraces the view that society is getting more complex, more dangerous, less manageable.

He could be sharply prescient in 1991: “The twenty-first century is expected to bring some of the most turbulent years in the history of this nation,” he wrote. “This turbulence is expected to put enormous new strains on our entire law enforcement and criminal justice system. It will make law enforcement more complex and dangerous.”

He was right, and while some of his predicted causes of turbulence were off the mark, many were not. He didn’t pick up on terrorism or immigration, for example. Rather, he cited “abortion, high levels of poverty, the homeless, chronic unemployment, school drop-outs, health care costs, and the perceived failure of many of our social and cultural institutions to be responsive to critical issues. While law enforcement is not required to attend to these issues directly law enforcement is often involved in their indirect consequences.” Again, he was off the mark when he projected “massive urban unrest and civil disturbances reminiscent of the mid-1960s and early 1970s,” but he perceived rising inequality, rising demand for government services and diminishing resource. If law enforcement is to meet the challenges, it would have to hone the skills of its “top cops” (Staly’s term) and those of the leaders within their organizations.

“A Cop’s Cop”

It can read like the how-to manual for a future sheriff. (An earlier article had outlined theories of leadership development and hiring practices, some of which he’s implemented in the past two years.) The thesis was eventually turned into a cover story for the January 1992 issue of The Florida Police Chief.

“I was right probably 80 percent of the time,” he now says. “I nailed it. But when I was off, I was way off.” He happened to say those words as he briefly patrolled through South Bunnell, the predominantly black, poorest and most neglected area of the county. “It’s poverty,” he says, driving along, drawing the occasional glare from eyes noticing the greenish glare within his car (it’s getting late Friday night), the braced computer screen, telltale sign of a cop’s wares, even in an unmarked black vehicle: South Bunnell’s residents aren’t easily fooled. He speaks of the neighborhood’s bedraggled condition. “It’s no education,” Staly continues, “it’s a generational cycle, and as a result it’s a haven for drug dealers. The sad part is there’s some great people living in South Bunnell. They don’t want that stuff here.”

As he heads for Flagler Beach, talk turns to cop violence, the recent spate of shootings of unarmed black men, the resentment it’s engendered and the inevitable standoffs between communities and the police agencies that serve them. Staly doesn’t see that in Flagler, where he says there’s more of a mutual respect, but he acknowledges that use-of-force problems begin at the top: if the leadership of a department tolerates it, it’ll contaminate the ranks. This leadership, he says, doesn’t. He says he’s analyzed the sheriff’s office’s use-of-force reports and sees no issue here.

And he tells another story for contrast, that of Kevin Byrne, the veteran sheriff’s corporal, who was dealing with a young man who kept getting in trouble. He’d forget to take his medication. Why couldn’t he remember? Because he had now watch. “And the deputy took his watch off and gave it to him, and said: now you can remember,” Staly said, referring to Byrne. The story was never told in a PR release for the press. It came up Friday evening, and it came up only because Byrne had mentioned it in passing, as a story to tell, to Staly’s wife during a chance encounter. When Staly found out, he went to Walmart and bought Byrne a new watch. “That’s an example of the unsung heroes that our deputies do that the public just doesn’t know about,” Staly said.

He doesn’t just love the job. He loves those deputies for what they do, the risks they take, the gestures that never see the ink of a news release.

Staly had started the evening patrol, by the Palm Coast Precinct at City Marketplace, shaking hands with a group of deputies, thanking them for their service and for his chance to work with them. Just past 11 p.m., he pulled up at the county jail. Deputies were going through the booking requirements for the woman who’d been arrested for DUI earlier on Boulder Rock. Staly waited out the process (the woman was eventually taken to the local hospital for medical clearance.) Cmdr. Tammy Stakes then took him to each wing of the jail so he could speak to every corrections deputy on the shift. His aim was to speak to every deputy in the agency that way, before his last day. “I really enjoyed the last two and a half years with the team,” he’d say in one variation to another at each stop—misdemeanor block, felony block, outside the cramped women’s dormitory. “Thanks for letting me be part of it.” There was no hurry, no sense that he was doing this out of duty.

After the jail he kept patrolling a little past midnight after finally being rid of the reporter who’d shadowed him all evening. But it would remain a quiet night: a couple of traffic stops for speeding on I-95 (“no tickets,” he said in an email), nothing more.

Then he went home, shift over.

Heading North says

As a retired Law Enforcement officer (3agencies) I can understand exactly what Undersheriff Staly is saying and agree with the lions share of all of it.

I spent 10 years in a small, and I mean small, agency where we had to beg for tires, and had only two patrol cars, then I moved to Florida, and my first application for employment was with FCSO, where I was told ” I ain’t having no Yankee on my department” by a long ago Sheriff!

I was a Florida State Trooper for 25 years, having been assigned to Flagler County for the last 20 of those years. Made a lot of friends, some enemies , but it was a great career! I even worked for FCSO for three more years, then family matters called me back to the North. I miss all my friends in Florida, but don’t miss Law Enforcement, like Rick says, it’s a young mans job now.

From another 40 year man Rick, best of luck, and Godspeed!

Doyle Lewis says

I hope law will get back to being helpful to the needy!!!!!

You have to enjoy life, only the way you make your home and bed!!!!!

blondee says

Thank you for your service Officer Staly!

confidential says

Farewell and Safe Retirement Mr Staly! I enjoyed your photos as a young kid and law enforcement officer. Brave man in a every day dead facing career.

As a 24 years resident of Palm Coast I can say that in the last six years our sheriff deputies have shown a higher professional, dedicated and compassionate work in our neighborhoods and I applaud them for that as I know that you and Sheriff Manfre at the helms, promote it.

Happy trails Mr. Staly!

Jason stryker says

I will say this very nicely as an alternative view. I am not sure that it will be posted but this is the truth. Staley was injured the line of duty and he deserves respect for that. He served Orange County with honor and he deserves respect for that. But when he came to be undersheriff under Manfre in my humble opinion he gave in to “dark side”. I worked for the Flagler County Sheriffs Office then. I no longer do. I left and the reason is simply because I personally witnessed Staley lie to officers and to the public. He fired many honorable veteran officers without just cause. Vietnam veterans who sacrificed for their country and served Flager for years like Major Claire. Marine veteran Lt Weston was fired without cause. The only female senior officer in Flagler County, Cpatain Cattiggo was fired. Undersheriff O’Brien who served for years in this county and who worked his way up the ranks. There are more….many more who served with honor and distinction. They were forced out and fired because Staley and Manfre wanted them out of the way. Staley was the “ax man” and everyone at the Sheriffs Office knows it. He is not respected among the ranks in Flagler. Our respect he never earned. That chance he lost the moment he cleared many out of the way-officers who he felt were in his way. Their story should be told here. They all worked hard to serve our community and were simply cast away by Staley. I personally will be at every debate Staley goes to simply to tell their story. Over 20% of this agency has either left or been fired. Honor? Distinction? Lost?

Buddy Negron says

Jason, you are clearly nothing more than a disgruntled ex-employee. It is abundantly clear and everyone that reads your lame comments can clearly see that. The fact that you would use this article honoring Undersheriff Staly’s decades of service in law-enforcement to besmirch him and put down the Flagler County Sheriffs Office because you were properly terminated from your position. You’re pathetic actually and your comments laughable. I look forward to seeing you at all of those debates so I can call you to the carpet on all of your BS, set the record straight, and support the correct candidate and tell the truth. Honor? Distinction? Words you know absolutely nothing about and hence why you no longer work in Law enforcement. Try plumbing or roofing, you may have better luck there since truth, morals, and ethics aren’t required for that job. Now crawl back under your rock and disappear. :)

Doug says

Plumbers and roofers are not truthful, moral or ethical? A lot more truthful and ethical than many police officers.

Footballen says

Farewell, take this opportunity (since you can afford it) and make up for all the nights and weeks you were not there for your family. Father time will never ever give you this chance again. Thank you so much for your service but it is your family that you now owe your attention.

Buddy Negron says

I would like to take a moment to thank Flaglerlive for the outstanding coverage and article about Undersheriff Staly, his history in Florida law enforcement and the truth in reporting. I would also like to thank Undersheriff Staly for his service, dedication, commitment, and sacrifice. FCSO is a far better place because of Rick Staly and I think that’s obvious to everyone (except Disgrutleled Jason, the former employee. Unlike his take, I have found the employees of FCSO enjoyed working with and for Undersheriff Staly. Additionally many believe he was the only true leader the agency has seen in decades. I’m sorry Jason feels otherwise, but as expand ex-employee p, I’m sure there is much more to his opinions than facts and objectivity. Nonetheless, congrats again to Undersheriff Staly for all of your accomplishments and thank you to Pierre for taking the time to cover it and accurately report his findings. God Bless and Stay Safe, Buddy